Turkey tail fungus: Difference between revisions

Created page with "== Introduction and Classification == right|200px|caption Commonly known as Turkey tail fungus and scientifically known as ''Trametes v..." |

No edit summary |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Turkey-tail-pores-1024x768.jpg|right|200px|caption]] | [[File:Turkey-tail-pores-1024x768.jpg|right|200px|caption]] | ||

''Trametes versicolor'', commonly known as turkey tail fungus, is utilized medicinally for a wide range of health benefits. Turkey tail is a [[saprobic]], or saprophytic fungus. This means it feeds solely upon decaying wood, [[decomposing]] and converting the dead matter into consumable material for other [[organisms]], as the wood is further broken down into mulch and then [[soil]]. | |||

== Taxonomy == | |||

====== | |||

= | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width:85%;"| | ||

= | |- | ||

= | | | ||

! scope="col" | Kingdom | |||

! scope="col" | Division | |||

! scope="col" | Class | |||

! scope="col" | Order | |||

! scope="col" | Family | |||

! scope="col" | Genus | |||

! scope="col" | Species | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Classification | |||

| Fungi | |||

| Basidomycota | |||

| Agaricomycetes | |||

| Polyporales | |||

| Polyporaceae | |||

| Trametes | |||

| T. versicolor | |||

|} | |||

== Appearance and Habitat == | == Appearance and Habitat == | ||

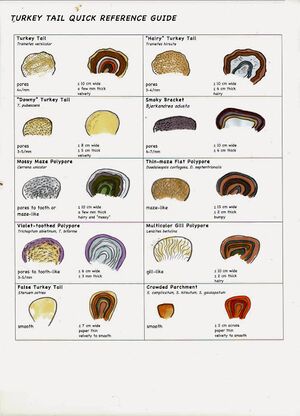

Turkey tail gets its name due to its resemblance to the tail of a turkey. The fan-shaped colorful | Turkey tail gets its name due to its resemblance to the tail of a turkey. The fan-shaped colorful stripes are similar to the tail feathers of a male turkey. Stripes of orange, green-blue, reddish-brown and white cover the velvety upper surface. It is fairly thin and pliable which is unusual for fungi of its genus, and the cups can grow up to 4 inches in width. The mushrooms often grow together in shelf-like layers and form clusters. Turkey tail is one of the most common fungi in North American forests. In the United States, it has been identified in almost all 50 states. It resides on hardwood logs and conifer trees. It prefers shady wet areas in temperate forests and may be found across Asia and Europe as well. In our backyard, it can be spotted in Letchworth Woods on UB’s North Campus. Turkey tail does not have a stalk, but rather the cup attaches to the tree or log it inhabits. Small hairs cover the dark stripes which differentiate the turkey tail from other fungi. Regarding texture, turkey tail is rough and leathery. Belonging to the polypore family, it has microscopic pores rather than gills which differentiate it from other fungi. Pores hold the spores that the fungus uses in reproduction, functioning similarly to gills. | ||

[[File:Figure-6-tt.jpg|right|300px|caption]] | [[File:Figure-6-tt.jpg|right|300px|caption]] | ||

== Life Cycle == | == Life Cycle == | ||

Turkey tail’s life cycle begins when wind blows haploid spores away from the pores. When they land in ideal conditions near other spores, they will grow into a germling. If grown together, during the plasmogamy life cycle stage, the two fungi will mesh their hyphae and mix cell content. Cells in the original germlings will contain different unfused nuclei, and the fungus stays in a dikaryotic state for the majority of its life. As time progresses, the conk of the polypore fungus, which is the fruiting body, will develop. The pore surface is located on the underside of the conk and covered with basidia. The basidia cells enable fusion of the nuclei in the dikaryotic cells, meiosis and the development of spores. Spores produced by basidia are known as basidiospores, and once they exit the basidia they may be carried by the wind to restart the cycle. The nature of their thick bodies allow them to survive through the winter, and can be seen growing on fallen logs in | Turkey tail’s life cycle begins when wind blows haploid spores away from the pores. When they land in ideal conditions near other spores, they will grow into a germling. If grown together, during the plasmogamy life cycle stage, the two fungi will mesh their hyphae and mix cell content. Cells in the original germlings will contain different unfused nuclei, and the fungus stays in a dikaryotic state for the majority of its life. As time progresses, the conk of the polypore fungus, which is the fruiting body, will develop. The pore surface is located on the underside of the conk and covered with basidia. The basidia cells enable fusion of the nuclei in the dikaryotic cells, meiosis, and the development of spores. Spores produced by basidia are known as basidiospores, and once they exit the basidia they may be carried by the wind to restart the cycle. The nature of their thick bodies allow them to survive through the winter, and can be seen growing on fallen logs in mid April. The tough thick layer also prevents them from freezing though the winter. | ||

[[File:Life cycle.jpg|right|200px|]] | [[File:Life cycle.jpg|right|200px|]] | ||

== Ecological Function == | == Ecological Function == | ||

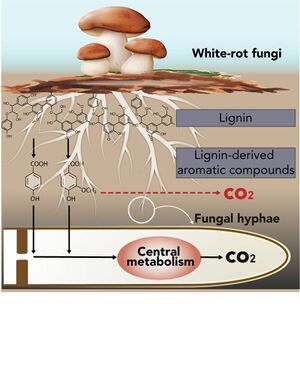

Turkey tail supports forests by breaking down dead wood, recycling nutrients back to the soil and allowing space for new growth. It is a type of white rot fungi which means it possesses the [[properties]] to break down [[lignin]] in wood and degrade the cell wall components. The turkey tail’s observable soft and stringy white appearance is the result of lignin [[decomposition]]. White rot fungus can | Turkey tail supports forests by breaking down dead wood, recycling nutrients back to the soil and allowing space for new growth. It is a type of white rot fungi which means it possesses the [[properties]] to break down [[lignin]] in wood and degrade the cell wall components. The turkey tail’s observable soft and stringy white appearance is the result of lignin [[decomposition]]. White rot fungus can be found widely in hardwood forests with birch and aspen trees as well as degrade softwood like spruce and pine. Turkey tail is among the white rot fungi studied because of its ability to treat different types of lignocellulosic waste as a natural treatment rather than using thermal or chemical processes. The tough lignin in tree cell walls can only be broken down by fungi. Remaining trees, young stands, and seedlings depend on nutrients in dead trees to survive and grow, and turkey tail helps decay, and thereby break down wood. Consequently, nutrients are supplied and reabsorbed by the released compounds. Another ecological service turkey tail provides is removing pollutants from wastewater and remediation of contaminated soils. | ||

[[File:Mushroom life cycle.png|right|300px|]] | [[File:Mushroom life cycle.png|right|300px|]] | ||

== Ability to Degrade Dyes == | == Ability to Degrade Dyes == | ||

''Trametes versicolor'', or Turkey Tail Fungus, has demonstrated success at degrading dyes and color from manufacturing and industry waste. Around 10,000 various dyes and pigments are produced globally each year from printing, textile, pharmaceuticals, toy and food manufacturing. Through processing methods, large amounts of dyes are lost and enter wastewater streams. Azo dyes are the most commonly used and are resistant to aerobic biodegradation processes. Once present in water systems, they are difficult to break down. | ''Trametes versicolor'', or Turkey Tail Fungus, has demonstrated success at degrading dyes and color from manufacturing and industry waste. Around 10,000 various dyes and pigments are produced globally each year from printing, textile, pharmaceuticals, toy, and food manufacturing. Through processing methods, large amounts of dyes are lost and enter wastewater streams. Azo dyes are the most commonly used and are resistant to aerobic biodegradation processes. Once present in water systems, they are difficult to break down. | ||

Studies have shown that among other white-rot fungi, | Studies have shown that among other white-rot fungi, trametes versicolor can break down compounds like lignin, xenobiotics (chemicals that are not normally produced by an organism or known to be associated with it) and dyes using nonspecific extracellular ligninolytic enzyme system. | ||

[[File:042921-ber-fungi.jpg|thumb|300px]] | [[File:042921-ber-fungi.jpg|thumb|300px]] | ||

== Use in Medicine == | == Use in Medicine == | ||

Turkey tail has been used in traditional medicine in China and Japan for general health benefits and boosting immunity. However, perceptions surrounding its effectiveness vary and studies are still ongoing. Its unique active compound, Polysaccharide K (PSK), is converted to capsule form for medication and has been prescribed in lung cancer patients in Japan since the 1970’s. Recently, studies have investigated its effectiveness in treating breast and prostate cancer. The US Food and Drug Administration has not approved the use of turkey tail or the compound PSK as treatment for cancer or general ailments. In the United States, it has also not been approved as a dietary supplement nor been declared safe or effective. However, the USFDA did approve it for a clinical trial in 2012 on prostate cancer patients on chemotherapy. No definitive results have been found regarding evidence of its effectiveness against various types of cancer. | Turkey tail has been used in traditional medicine in China and Japan for general health benefits and boosting immunity. However, perceptions surrounding its effectiveness vary and studies are still ongoing. Its unique active compound, Polysaccharide K (PSK), is converted to capsule form for medication and has been prescribed in lung cancer patients in Japan since the 1970’s. Recently, studies have investigated its effectiveness in treating breast and prostate cancer. The US Food and Drug Administration has not approved the use of turkey tail or the compound PSK as treatment for cancer or general ailments. In the United States, it has also not been approved as a dietary supplement nor been declared safe or effective. However, the USFDA did approve it for a clinical trial in 2012 on prostate cancer patients on chemotherapy. No definitive results have been found regarding evidence of its effectiveness against various types of cancer. | ||

Turkey tail is also consumed as a tincture, tea or eaten. To create a tincture, simply cut pieces of the mushroom and place it in 40-50% alcohol for two weeks and then strain the liquid. To make tea, slowly boil the mushroom for 90 minutes. The hot water works to break down chitin, which makes up the structure of the mushroom and is too tough for humans to plainly digest. Some add turkey tail into slow cooked meals like strews and roasts. | Turkey tail is also consumed as a tincture, tea, or eaten. To create a tincture, simply cut pieces of the mushroom and place it in 40-50% alcohol solution for two weeks, and then strain the liquid. To make tea, slowly boil the mushroom for 90 minutes. The hot water works to break down chitin, which makes up the structure of the mushroom and is too tough for humans to plainly digest. Some add turkey tail into slow cooked meals like strews and roasts. | ||

== Works Cited == | == Works Cited == | ||

Latest revision as of 22:34, 12 May 2022

Trametes versicolor, commonly known as turkey tail fungus, is utilized medicinally for a wide range of health benefits. Turkey tail is a saprobic, or saprophytic fungus. This means it feeds solely upon decaying wood, decomposing and converting the dead matter into consumable material for other organisms, as the wood is further broken down into mulch and then soil.

Taxonomy

| Kingdom | Division | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Fungi | Basidomycota | Agaricomycetes | Polyporales | Polyporaceae | Trametes | T. versicolor |

Appearance and Habitat

Turkey tail gets its name due to its resemblance to the tail of a turkey. The fan-shaped colorful stripes are similar to the tail feathers of a male turkey. Stripes of orange, green-blue, reddish-brown and white cover the velvety upper surface. It is fairly thin and pliable which is unusual for fungi of its genus, and the cups can grow up to 4 inches in width. The mushrooms often grow together in shelf-like layers and form clusters. Turkey tail is one of the most common fungi in North American forests. In the United States, it has been identified in almost all 50 states. It resides on hardwood logs and conifer trees. It prefers shady wet areas in temperate forests and may be found across Asia and Europe as well. In our backyard, it can be spotted in Letchworth Woods on UB’s North Campus. Turkey tail does not have a stalk, but rather the cup attaches to the tree or log it inhabits. Small hairs cover the dark stripes which differentiate the turkey tail from other fungi. Regarding texture, turkey tail is rough and leathery. Belonging to the polypore family, it has microscopic pores rather than gills which differentiate it from other fungi. Pores hold the spores that the fungus uses in reproduction, functioning similarly to gills.

Life Cycle

Turkey tail’s life cycle begins when wind blows haploid spores away from the pores. When they land in ideal conditions near other spores, they will grow into a germling. If grown together, during the plasmogamy life cycle stage, the two fungi will mesh their hyphae and mix cell content. Cells in the original germlings will contain different unfused nuclei, and the fungus stays in a dikaryotic state for the majority of its life. As time progresses, the conk of the polypore fungus, which is the fruiting body, will develop. The pore surface is located on the underside of the conk and covered with basidia. The basidia cells enable fusion of the nuclei in the dikaryotic cells, meiosis, and the development of spores. Spores produced by basidia are known as basidiospores, and once they exit the basidia they may be carried by the wind to restart the cycle. The nature of their thick bodies allow them to survive through the winter, and can be seen growing on fallen logs in mid April. The tough thick layer also prevents them from freezing though the winter.

Ecological Function

Turkey tail supports forests by breaking down dead wood, recycling nutrients back to the soil and allowing space for new growth. It is a type of white rot fungi which means it possesses the properties to break down lignin in wood and degrade the cell wall components. The turkey tail’s observable soft and stringy white appearance is the result of lignin decomposition. White rot fungus can be found widely in hardwood forests with birch and aspen trees as well as degrade softwood like spruce and pine. Turkey tail is among the white rot fungi studied because of its ability to treat different types of lignocellulosic waste as a natural treatment rather than using thermal or chemical processes. The tough lignin in tree cell walls can only be broken down by fungi. Remaining trees, young stands, and seedlings depend on nutrients in dead trees to survive and grow, and turkey tail helps decay, and thereby break down wood. Consequently, nutrients are supplied and reabsorbed by the released compounds. Another ecological service turkey tail provides is removing pollutants from wastewater and remediation of contaminated soils.

Ability to Degrade Dyes

Trametes versicolor, or Turkey Tail Fungus, has demonstrated success at degrading dyes and color from manufacturing and industry waste. Around 10,000 various dyes and pigments are produced globally each year from printing, textile, pharmaceuticals, toy, and food manufacturing. Through processing methods, large amounts of dyes are lost and enter wastewater streams. Azo dyes are the most commonly used and are resistant to aerobic biodegradation processes. Once present in water systems, they are difficult to break down. Studies have shown that among other white-rot fungi, trametes versicolor can break down compounds like lignin, xenobiotics (chemicals that are not normally produced by an organism or known to be associated with it) and dyes using nonspecific extracellular ligninolytic enzyme system.

Use in Medicine

Turkey tail has been used in traditional medicine in China and Japan for general health benefits and boosting immunity. However, perceptions surrounding its effectiveness vary and studies are still ongoing. Its unique active compound, Polysaccharide K (PSK), is converted to capsule form for medication and has been prescribed in lung cancer patients in Japan since the 1970’s. Recently, studies have investigated its effectiveness in treating breast and prostate cancer. The US Food and Drug Administration has not approved the use of turkey tail or the compound PSK as treatment for cancer or general ailments. In the United States, it has also not been approved as a dietary supplement nor been declared safe or effective. However, the USFDA did approve it for a clinical trial in 2012 on prostate cancer patients on chemotherapy. No definitive results have been found regarding evidence of its effectiveness against various types of cancer. Turkey tail is also consumed as a tincture, tea, or eaten. To create a tincture, simply cut pieces of the mushroom and place it in 40-50% alcohol solution for two weeks, and then strain the liquid. To make tea, slowly boil the mushroom for 90 minutes. The hot water works to break down chitin, which makes up the structure of the mushroom and is too tough for humans to plainly digest. Some add turkey tail into slow cooked meals like strews and roasts.

Works Cited

- Lisa Turner. “Super Mushrooms.” Better Nutrition, vol. 82, no. 3, Active Interest Media, 2020, pp. 22–23.

- Braesel, Jana, et al. “Biochemical and Genetic Basis of Orsellinic Acid Biosynthesis and Prenylation in a Stereaceous Basidiomycete.” Fungal Genetics and Biology, vol. 98, Elsevier Inc, 2017, pp. 12–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2016.11.007.

- Hodgkins, Fran. “Turkey Tail Mushroom.” The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine: T-Z, Organizations, Glossary, Index, 2020, pp. 2700–02.