Dead Man's Fingers

Dead Man’s Fingers, or Xylaria polymorpha, is a saprobic (saprophytic) and weakly parasitic fungus that is characterized by its club-shaped fruiting bodies that emerge from the soil in clusters such that it looks like a corpse’s hand is reaching up through the ground. As an ascomycete, it breaks down glucan in woody plants via the soft rot mechanism and can reproduce sexually or asexually. The scientific name refers to a species complex of several closely related species that cannot be easily distinguished. Hardwood trees that are susceptible to black root rot from infection include apple, crabapple, pear, cherry, plum, elm, maple, locust, oak, hickory, sassafras, walnut, and beech. It is inedible.

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Xylariales |

| Family: | Xylariaceae |

| Genus: | Xylaria |

| Species: | X. polymorpha |

Taxonomy

X. polymorpha is in the phylum Ascomycota, which is commonly known as the sac fungi and is the largest phylum of fungi containing about 65,000 species. Furthermore, it is in the family Xylariaceae which is one of the largest and most diverse families of filamentous Ascomycota.[1]

Xylaria means “growing on wood,” while polymorpha means “many forms.”[2] Xylaria polymorpha is actually a species complex which may consist of anywhere from 5-10 species that are difficult to distinguish from each other.[2]

Description

Dead Man’s Fingers are the mushroom-like fruiting bodies of X. polymorpha that can be found on or near dead or dying wood as well as wooden barrels that are in contact with the soil.[5] The “fingers” of the fungus emerge from the ground either as a single fruiting body or in groups of typically 3-6 which can be fused together.[2][3] The form and number of fruiting bodies is highly variable.[2] The fingers are usually 1-3 in. tall and ½ -1 ¼ in. wide.[2][5][3][6] When young, the fungus is a pale white, gray, or blue with white caps that often resemble finger nails, as seen in Figure 1.[5] As it matures, the fingers turn charcoal black and their smooth “skin” takes on the appearance of charcoal as seen in Figure 2.[6] If broken open, the interior of the fingers is white and tough.[5] These fungi are active June through October but can be found throughout the year.[6] These fungi are not edible.[6] Its spore print is dark brown to black, and when magnified, the spores appear as narrow and spindle-shaped, flat on one side.[6]

Ecosystem Role

The Dead Man’s Fingers fungus is primarily a saprophyte that obtains nutrients from dead woody plants. It plays an important ecological role in cleaning the forest and cycling nutrients back into the soil. Like other filamentous Ascomycetes, X. polymorpha decomposes wood through a soft rot process.[2] For comparison, brown rot fungi break down the cellulose in plant matter, leaving behind the brown lignin and white rot fungi break down the lignin, leaving the white cellulose.[2] However, soft rot fungi break down the glucan and other glues between the cellulose and lignin, which compromises the structure of the wood and leaves a mushy mass of cellulose and lignin.[2] The soft rot mechanism is less effective at removing nutrients than the brown and white rot mechanisms.[2]

X. polymorpha can also be a parasite on stressed deciduous trees, causing black root rot.[5] The fungus forms an off-white sheath around plant roots which eventually turns black and crusty, concealing the white interior.[5] The fungus can survive as hyphae inside of dead or dying wood for up to 15 years, and they spread between individuals when plant roots come in contact with each other.[5][7] Certain trees are more susceptible to infection, including apple, crabapple, pear, cherry, plum, elm, maple, locust, oak, hickory, sassafras, walnut, and beech.[5][3][7] The fungus can also invade stressed ornamental trees and shrubs.[3] Although trees of any age can be infected, typically only trees that are older than ten years die from infection.[7] If Dead Man’s Fingers are found at the base or in the vicinity of a tree, it is possible that it is infected.[5] Other signs of infection include losing foliage, dying back, slowed growth, basal cankers, and eventually the tree may start to lean and break at the base of its trunk.[5][7] Specifically, infected apple trees may produce a larger-than-normal crop of smaller-than-normal fruits.[5]

Reproduction

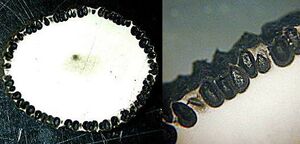

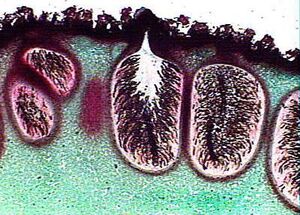

The Dead Man’s Fingers are the reproductive structure of X. polymorpha. The white inside of the fingers is a made up of a dense mass of hyphae called the stroma.[2] The outer surface of the stroma is covered with little black flask-shaped structures called perithecia, as seen in Figure 3.[2] Each perithecium contains asci which in turn contain ascospores, or sexual spores.[2] Each ascus takes its turn elongating into the ostiole (small pore in the side of the perithecium facing away from the fungus) and discharging its ascospores into the environment as seen in Figure 4.[2] It takes months or even years for each ascus to release all of its spores, while most mushrooms that people are familiar with release their spores over the course of a few hours or days each year.[2] In the springtime, Dead Man’s Fingers also has the ability to release a layer of white asexual spores called conidia over its entire surface, which is known as the “candlesnuff phase.”[2][5]

How to Prevent/Treat Infection

To stave off infection, trees should be kept well-hydrated and fertilized to keep their immune system strong. Rootstocks that are less susceptible to infection should be used.[7] For example, the MM.106 and seedling apple rootstocks are less susceptible than MM.104 and MM.111 rootstocks, although none are resistant.[7]

Dead Man’s Fingers is only a weak pathogen and induces a slow rot, so an infected host has the chance to recover and the tree/shrub should not be removed immediately.[3] It is also possible that Dead Man’s Fungus is feeding on the mulch around a plant and not the roots of the plant itself.[5] On the other hand, by the time that the fruiting bodies appear, the infection is well advanced in the plant.[5] The plant should be tended to closely and provided with sufficient water and nutrients to see if it can fight off the disease.[5]

If the tree cannot be saved, then the entire stump and as much of the root system as possible should be removed and planting in the same location should be avoided.[5] If replanting is necessary, then the area should be deep plowed, stripped of any remaining roots, and left fallow for as long as possible.[7] Remember that the fungus can survive in wood remnants for up to 15 years. Susceptible plants should not be planted in the same site.[5] Peach trees are not susceptible and are a good substitute.[7]

References

- ↑ U'Ren JM, Miadlikowska J, Zimmerman NB, Lutzoni F, Stajich JE, Arnold AE. Contributions of North American endophytes to the phylogeny, ecology, and taxonomy of Xylariaceae (Sordariomycetes, Ascomycota). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016 May; 98:210-32. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.02.010 Epub 2016 Feb 20. PMID: 26903035.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Volk TJ of University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. (2000, April). Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for April 2000. TomVolkFungi.net. http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/apr2000.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Davey Tree. (n.d.) Dead Man’s Fingers Fungus. https://www.davey.com/insect-disease-resource-center/dead-mans-fingers/

- ↑ Highfield, C. (2019, October 28). From the Grave: Dead Man’s Fingers. Alliance for the Chesepeake Bay. https://www.allianceforthebay.org/2019/10/from-the-grave-dead-mans-fingers/

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 Joy, A. and Hudelson, B., UW-Madison Plant Pathology. (2012, August 13). Dead Man’s Fingers. Wisconsin Horticulture Divison of Extension. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/dead-mans-fingers/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Missouri Department of Conservation. (n.d.) Dead Man’s Fingers.https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/dead-mans-fingers

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Biggs, A.R., West Virginia University. (2019, August 22). ‘’’Black Root Rot of Apple.’’’ National Institute of Food and Agriculture Cooperative Extension. https://apples.extension.org/black-root-rot-of-apple/