Ascomycota

Ascomycota is a phylum of fungi characterized by their formation of a sac-like structure or “ascus” [1]. It is the largest phylum of fungi species, accounting for approximately 75% of all described fungi, with over 65,000 species [3]. This group is also referred to as “Ascomycetes”, or "Sac Fungi". Ascomycota together with Basidiomycota form the subkingdom Dikarya [4]. Many ascomycetes are of commercial importance and some play a beneficial role, such as the yeasts, truffles and morels [1]. Among the famous Ascomycota fungi: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast of commerce and foundation of the baking and brewing industries, Penicillium chrysogenum, producer of penicillin, Morchella esculentum, the edible morel, and Neurospora crassa, the "one-gene-one-enzyme" organism [3]. Infamous Ascomysetes include: Aspergillus flavus, producer of aflatoxin (the fungal contaminant of nuts and stored grain that is both a toxin and the most potent known natural carcinogen), Candida albicans, cause of thrush, diaper rash and vaginitis, and Cryphonectria parasitica, responsible for the demise of 4 billion chestnut trees in the eastern USA [5].

Reproduction

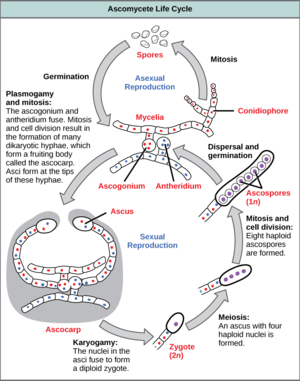

Ascomycota can make spores sexually (ascospores or meiospores) and asexually (condia or mitospores) [3]. Asexually, the hyphae of the sac fungi are divided by septa with pores, that is, they have perforated walls between adjacent cells [6]. They reproduce asexually by producing spores, called conidia, which are born on specialized erect hyphae, called conidiophores. The sac fungi are typically prolific producers of conidia [6]. Sexual reproduction begins with the development of particular hyphae from either one of two types of mating strains. The “male” strain produces an antheridium and the “female” strain develops an ascogonium [1]. At fertilization, the antheridium and the ascogonium combine without nuclear fusion. Special ascogenous hyphae arise, in which pairs of nuclei migrate: one from the “male” strain and one from the “female” strain. In each ascus, two or more haploid ascospores fuse their nuclei [1]. During sexual reproduction, thousands of asci (ascus, plural) fill a fruiting body called the ascocarp. The ascospores are then released, germinate, and form hyphae that are disseminated in the environment and start new mycelia [1]. Wind is the primary dispersal agent once the spores have been released from the ascus, but splashing, running water, and animals can be a method of spore transport as well [3].

Subgroups

Ascomycota, which includes both unicellular and multicellular forms, is divided into three monophyletic subphyla: Pneumocystidomycetes, Schizosaccharomycetes, and Taphrinomycetes. Pezizomycotina is the largest subphylum of Ascomycota, including the vast majority of filamentous, ascocarp-producing species of ascomycetes [7]. It is ecologically diverse with species functioning in ecological processes and symbioses including wood and litter decay, animal and plant pathogens, mycorrhizae, endophytes and lichens [9]. Saccharomycotina includes all types yeasts, some chategorized as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Bakers' Yeast, the most famous and economically important fungus, and Candida albicans, the most frequently encountered fungal pathogen of humans and often the agent responsible for vaginal yeast infections and thrush and some toenail infections, among others human medical woes [3, 7, 10]. Taphrinomycotina includes, among others, Pneumocystis jirovecii, a fungus that is often present in the lungs of healthy people but can cause pneumocystosis in individuals with weakened immune systems [7].

Characteristics

Ascomycota can be found on all continents and many genera and species display a cosmopolitan distribution [3]. They occur in terrestrial, marine, and freshwater habitats and range from microscopic to the size of large "mushrooms" [7]. The body of Ascomycota is shared by other fungi and consists of a typical eukaryotic cell surrounded by a wall [3]. The body can be a single cell, as in yeasts, or a long tubular filament divided into cellular segments (hypha), and both the yeasts and hyphae cell walls are made of varying proportions of chitin and beta glucans [3]. The association of Sac Fungi with its sister group Basidiomycota, is supported by the presence in members of both phyla of cross-walls (septa) that divide the hypahe into segments, and pairs of unfused nuclei in these segments after mating and before nuclear fusion [3].

References

[1] Learning, Lumen. “Biology for Majors II.” Lumen, Open SUNY Textbooks, courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-biology2/chapter/ascomycota/.

[2] “Sac Fungi.” Silk Tree or Mimosa, ALBIZIA JULIBRISSIN, www.backyardnature.net/fungsac.htm.

[3] Taylor, John W., Joey Spatafora, and Mary Berbee. 2006. Ascomycota. Sac Fungi. Version 09 October 2006 (under construction). tolweb.org/Ascomycota/20521/2006.10.09

[4] “Sac Fungi (Phylum Ascomycota).” INaturalist.org, www.inaturalist.org/taxa/48250-Ascomycota.

[5] Alexopoulos, C. J., C. W. Mims, and M. Blackwell. 1996. Introductory Mycology. John Wiley and Sons, New York. 868p.

[6] Rahima. “Fungi - Ascomycota, Sac Fungi.” Carbon, Energy, Greenhouse, and Atmosphere - JRank Articles, science.jrank.org/pages/2893/Fungi-Ascomycota-sac-fungi.html.

[7] “Ascomycetes - Ascomycota - Overview.” Encyclopedia of Life, eol.org/pages/5577/overview.

[8] “Simon's Blog - Winter Fungus.” ITV News, ITV Hub, www.itv.com/news/meridian/2016-02-04/simons-blog-winter-fungus/.

[9] Spatafora, Joey. 2007. Pezizomycotina. Version 19 December 2007. tolweb.org/Pezizomycotina/29296/2007.12.19

[10] Blackwell, Meredith, Cletus P. Kurtzman, Marc-André Lachance, and Sung-Oui Suh. 2009. Saccharomycotina. Saccharomycetales. Version 22 January 2009. tolweb.org/Saccharomycetales/29043/2009.01.22