Saprotrophic nutrition

Saprotrophic nutrition is an example of extracellular digestion of decayed organic matter by organisms such as fungi and soil bacteria. Saprotrophic microscopic fungi are often called saprobes; saprotrophic plants or bacterial flora are called saprophytes. The process is most often facilitated by active transport of such materials through endocytosis within the internal mycelium and its constituent hyphae. Fungi, bread mould, some protists, and many bacteria are saprophytic in nutrition. Saprobes often use their hyphae to penetrate wood and other solid materials. Saprotrophic bacteria are more adept at breaking down fluid and semi-fluid materials [2].

Process

In the presence of decaying organic matter, saprophytes and saprobes release digestive enzymes in their surrounding medium to convert complex organic molecules down to their simpler constituents. This simpler food is then absorbed through the body surface and utilized for various metabolic activities in the saprophyte. An example of this is the breakdown of starch into glucose or sucrose [1].

- Proteins are broken down into their amino acid components via the breaking of peptide bonds

- Lipids are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol

- Starch is broken down into simpler sugars

Conditions

Optimal growth and repair of saprophytic organisms requires favorable conditions [1].

- Presence of water: 80–90% of the body of a fungi is comprised of water by mass. Fungi require excess water in their environment for intake due to the evaporation of internally retained water.

- Presence of oxygen: Anaerobic conditions do not allow for the optimal growth of saprophytic organisms above media such as soil and water.

- Neutral pH: pH levels around 7 are required.

- Moderate temperatures: Optimal growth of saprotrophic organisms occurs at 25°C, most of these organisms can grow and thrive between the temperatures of 1°C and 35°C.

Occurrence in Nature

Materials Colonized by Saprotrophic Organisms [2]

Wood

Fungi are the fundamental decomposers of wood. Without the ecosystem services provided by fungi as wood decomposers, our forests would be filled with wood piles. There are two physiological types of wood-decay fungi recognized by those who work in the field: those that produce brown rots and those that produce white rots. These two physiological categories reflect the composition of the wood and the processes by which the fungi decompose the wood. Glucose stored in the wood is a vital nutrient for fungi that is sometimes difficult to obtain due to its binding in cellulose and lignin. Those fungi that digest the cellulose within the lignin matrix leave behind a mass of brown lignin. Those fungi that cause white rot dissolve the lignin first and leave behind the white fibrous cellulose for later digestion. The most efficient wood-decay fungi are members of the Basidiomycota and can be seen on decaying logs, stumps, and trees.

Fallen Leaves/Leaf Litter

Fallen leaves offer an abundant source of cellulose for forest ecosystems and their organisms. Some organisms begin their lives as endophytes and begin digesting the cellulose as soon as possible while other organisms occupy the leaves after they have fallen and begin rapidly digesting the cellulose. Leaves contain less lignin than wood so their soft parts are much easier to break down and digest. All types of leaves are colonized and decomposed by saprotrophic fungi.

Wrack

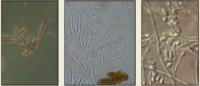

Wrack is biomass consisting of vegetable matter made up of a variety of species such as algae, seagrass and some land plants that may have washed up on beaches. It is very high in nutrients and has been used by humans as a fertilizer. While wrack is highly nutritious, its chemical components are rather unusual and not typically found outside of marine ecosystems. Because of this, the fungi associated with the decomposition of wrack are also found in marine habitats. Dendryphiella salina is the chief fungi that decomposes wrack and can be found worldwide. It is a slow-growing mould that is often found in the company of Sigmoidea marina and Acremonium fuci. Species of the ascomycete family Halosphaeriaceae are able to wait for wrack on beaches by attaching themselves to sand grains and releasing spores with bristle-like appendages that keep them suspended in seafoam.

Dung

Like wrack, dung is highly nutritious and full of useful compounds for the growth of organisms. Unlike wrack, dung supports a vast array of fungi, each highly adpted to finding and colonizing it. There are several ways that this is accomplished, ways that may involve very complex steps. There exist a wide variety of coprophilous saprophytes and saprobes. These dung loving organisms are diverse in their distribution, physiology and dung preference. Coprophilous fungi disperse spores into the air that can stick to herbivore food sources, the spores are then digested by the herbivores which in turn begins their germination stage. Some fungi do not disperse their spores away from the dung and instead produce slimy spores that adhere to the bodies of foraging flies, beetles and mites. These foragers then become hosts to the spores and carry them to the next dung pile where the fungi begins anew.

References

1. Clegg & Mackean (2006, p. 296), fig 14.17—A diagram explaining the optimal conditions needed for successful growth and repair

2. D. Malloch, Natural History of Fungi, (A part of the Mycology Web Pages, New Brunswick Museum. [1] 2017)

3.

4.