Red Velvet Ant

| |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Mutillidae |

| Genus: | Dasymutilla |

| Species: | Dasymutilla occidentalis |

Description

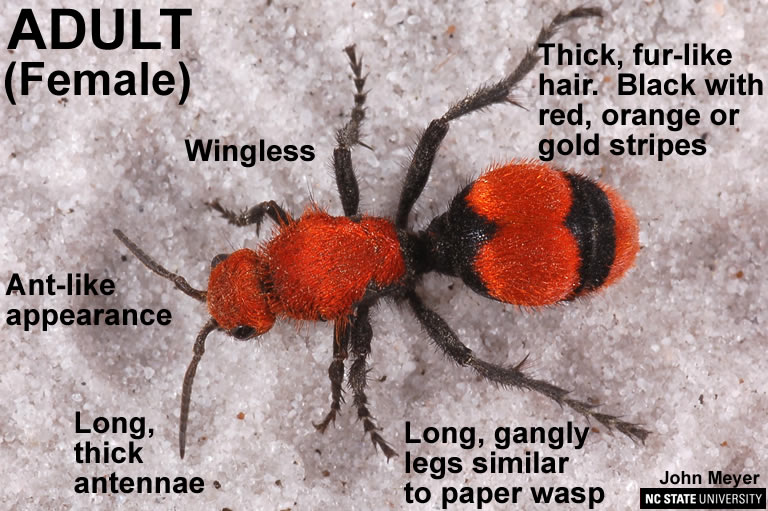

Red Velvet Ants belong to the Mutillidae family, which includes over 7,000 different species of velvet ants. Despite their name and appearance, Red Velvet Ants are actually a species of wasp. Like most wasps, they are solitary and do not form large hives. These wasps get their name from the short, red and black velvety hairs covering their bodies[1]. In addition to their aposematic coloration, females can produce a squeaking sound to deter predators. Red Velvet Ants are the largest of the velvet ant species, measuring about ¾ of an inch in length. Females are wingless, while males have dark, translucent wings. The females’ wingless appearance and their ground-dwelling behavior are why these insects are often mistaken for ants. Females also possess a powerful stinger, while males do not. These wasps are commonly known as “cow killers” due to the strength and pain of their sting.

Habitat and Range

Red Velvet Ants are native to North America. Their main range is the eastern United States. In the north, the range is Connecticut to Missouri, while in the south it's Florida to Texas[2]. They are often found in open, dry, and sandy areas with a lot of sun[3][4]. Red velvet Ants are parasites and rely on host species for their reproduction style. Because of this they tend to be found in the same areas where ground nesting wasps and bees can live[4].

Behavior and Life Cycle

Red Velvet Ants are solitary and do not form eusocial hives like hornets do. They are diurnal and rest during the night. Adults feed on nectar from plants, while their young are strictly parasitic. They are generally non aggressive and will not attack other species outside of their reproductive cycle. The only time a Red Velvet Ant comes into contact with one another is to mate[5].

They begin reproducing in the warmer months of the year. Females tend to be seen scurrying across open fields while males fly in the air in search of a mate. Once males locate a female through pheromones or hearing females squeaking, they pick the female up with their mandibles and fly away. The males will then find a spot deemed safe to mate, typically in a shaded area and away from other competitors. Once the process is over, the female will then begin to look for suitable hosts to lay their eggs. Red Velvet Ants prey on numerous different species of ground bees and wasps. The most common host they use are wasps of Crabronidae such as Eastern Cicada Killers and Horse Guard Wasps. Once they locate the ground nest of a host, they will lay a single egg in one of the nests chambers and then leave. It is believed that these wasps mate only once in their lifetime[5].

Roughly 3 days after being laid, the egg will hatch. The Red Velvet Ant larvae will then begin to eat the larvae or pupae of the host species. It will feed until it is ready to enter its pupal stage. The pupal stage typically takes around 20 days to complete, however the pupae will stay inside the nest chamber to overwinter if temperatures are not warm enough. Once ambient temperatures begin to rise after winter, they begin to emerge and look for mates. Most individuals emerge typically in July or August, however those that overwinter will emerge earlier in spring[5].

Defenses

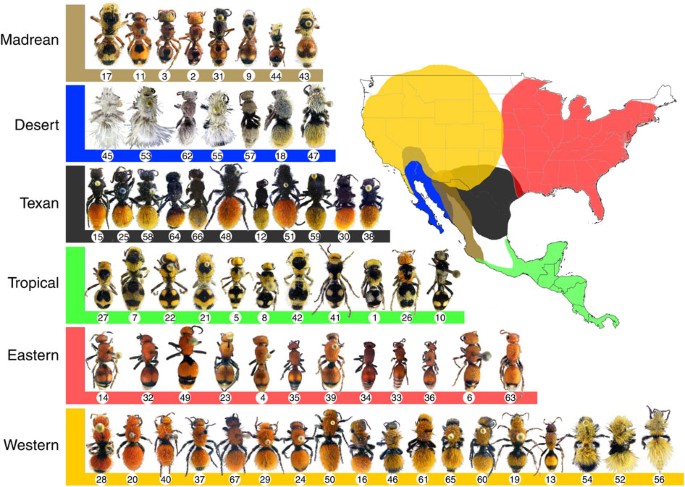

The Red Velvet Ant has a number of defenses in order to protect itself. Its most apparent defense is its aposematic coloration. Its bright red hairs contrasted with the dark black makes the Red Velvet ant a striking insect to look at. Their aposematic coloration is even more significant for the Red velvet Ant when looking at all the species of North American Multillidae (Velvet Ants). These Velvet Ants have complex Mullerian mimicry rings seen in the natural world. Mullerian mimicry refers to when two well-defended species have come to mimic each other's honest warning signals. The Velvet Ants of North America can be divided into 8 unique rings of mimicry that are tied to their location[6]. Velvet Ants in the east such as the Red Velvet Ant have similar, fiery coloration. However, tropical Velvet Ants found in Central America are black and yellow, similar to other wasps and bees. Desert Velvet Ants are more white in appearance, and the populations in texas only have coloration on their thorax. When studying all 21 genera of Velvet Ant in North America, only 15 of the 351 species found did not fit into one of the eight mimicry ring[6]s. This system of mimicry helps each species in its own unique environment be seen as not an easy prey item.

Female Red Velvet Ants main defense method outside of coloration is to run away, and when cornered they will even begin to make noises[4]. Their last line of defense is their incredibly long ovipositor which can act as a stinger to inject venom. Velvet Ant venom is noted to be 25 times less toxic than a honeybee, but far more painful. The sting is non-life threatening, however the pain is very intense and can last for sometimes 30 minutes. They are unlikely to use their stinger unless provoked to do so. This is due to the stinger's main function as the Red Velvet Ants ovipositor, making it not worth the risk of using. Eusocial bees and wasps rely on a queen for reproduction, allowing for free use of their stingers and much higher forms of aggression suitable for their species. Red velvet Ants also have a remarkably tough and thick exoskeleton, making them quite sturdy as well.

References

[1] [7] [2] [4] [8] [3] [5] [9] [10] [11] [6]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 “Arthropod Museum, Dept. of Entomology, University of Arkansas,” May 26, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120526173101/http://www.uark.edu/ua/arthmuse/cowkil.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 iNaturalist. “Red Velvet Ant (GTM Research Reserve Arthropod Guide) · iNaturalist.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/278784.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 “Red Velvet Ant or ‘Cow Killer,’” September 2, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110902230354/http://insects.tamu.edu/fieldguide/cimg344.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Missouri Department of Conservation. “Velvet Ants.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/velvet-ants.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Smith, Caleb. “Dasymutilla Occidentalis.” Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 20, 2025. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Dasymutilla_occidentalis/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wilson, Joseph S., Kevin A. Williams, Matthew L. Forister, Carol D. von Dohlen, and James P. Pitts. “Repeated Evolution in Overlapping Mimicry Rings among North American Velvet Ants.” Nature Communications 3, no. 1 (December 11, 2012): 1272. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2275.

- ↑ Field Guide to Common Texas Insects. “Red Velvet Ant or ‘Cow Killer.’” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://texasinsects.tamu.edu/red-velvet-ant-or-cow-killer/.

- ↑ “Red Velvet Ant; Cow Killer | Arthropod Museum.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://arthropod.uark.edu/red-velvet-ant-cow-killer/.

- ↑ “Species Dasymutilla Occidentalis - Common Eastern Velvet Ant.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://bugguide.net/node/view/13126/data.

- ↑ “Velvet Ant.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/biological-control-information-center/beneficial-parasitoids/velvet-ant/.

- ↑ “Velvet Ants: Flamboyant and Fuzzy with Extreme PPE | Natural History Museum.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/velvet-ants-flamboyant-and-fuzzy-with-extreme-ppe.html.