Red Velvet Ant

| |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Mutillidae |

| Genus: | Dasymutilla |

| Species: | Dasymutilla occidentalis |

Description

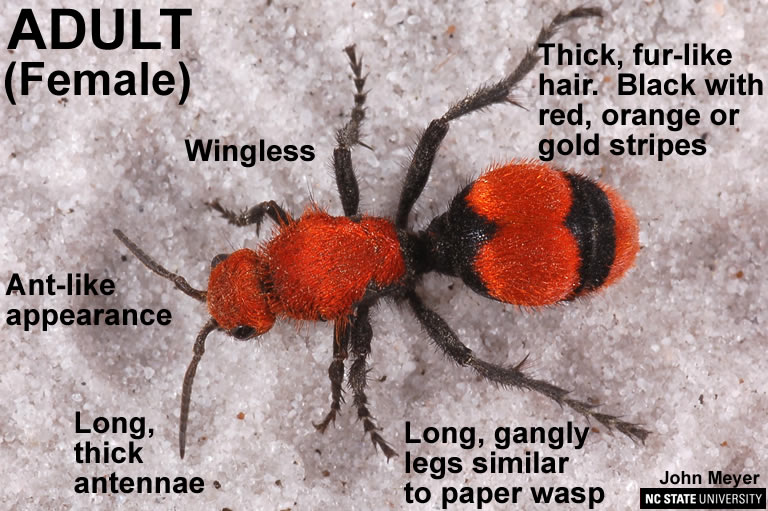

Red Velvet Ants belong to the Mutillidae family, which includes over 7,000 different species of velvet ants. Despite their name and appearance, Red Velvet Ants are actually a species of wasp. Like most wasps, they are solitary and do not form large hives. These wasps get their name from the short, red and black velvety hairs covering their bodies[1]. In addition to their aposematic coloration, females can produce a squeaking sound to deter predators. Red Velvet Ants are the largest of the velvet ant species, measuring about ¾ of an inch in length. Females are wingless, while males have dark, translucent wings. The females’ wingless appearance and their ground-dwelling behavior are why these insects are often mistaken for ants. Females also possess a powerful stinger, while males do not. These wasps are commonly known as “cow killers” due to the strength and pain of their sting.

Habitat and Range

Red Velvet Ants are native to North America, with their primary range in the eastern United States. In the north, they are found from Connecticut to Missouri, while in the south, their range extends from Florida to Texas[3]. They are often found in areas with dry, sandy soils that receive a lot of sunlight[4][5]. Red Velvet Ants are parasitic and rely on host species for reproduction. Because of this, they tend to be found in areas where ground-nesting hymenoptera are found[5].

Behavior and Life Cycle

Red Velvet Ants are solitary and do not form eusocial hives like hornets. They are diurnal, resting at night, and are generally non-aggressive, avoiding interaction with other species outside of their reproductive cycle. Adults feed on nectar from plants, while their young are strictly parasitic. The only time Red Velvet Ants interact with one another is to mate [8].

Reproduction begins in the warmer months of the year. Females are often seen scurrying across open fields, while males fly overhead in search of mates. Males locate females using pheromones or by hearing their characteristic squeaking sounds. Once a male finds a female, he picks her up with his mandibles and flies away. Mating typically occurs in a shaded area, away from other competing males. After mating, the female searches for suitable host nests in which to lay her eggs. Red Velvet Ants parasitize a variety of ground-nesting bees and wasps. Their most common hosts include wasps from the Crabronidae family, such as Eastern Cicada Killers and Horse Guard Wasps. Once a suitable nest is found, the female lays a single egg in one of the nest’s chambers and then departs. It is believed that Red Velvet Ants mate only once in their lifetime [8].

Approximately three days after being laid, the egg hatches. The Red Velvet Ant larva then begins feeding on the host's larva or pupa. After consuming the host, it enters its own pupal stage, which typically lasts around 20 days. However, if environmental temperatures are too low, the pupa will remain in the nest chamber to overwinter. When ambient temperatures rise, the adult emerges and begins searching for mates. Most individuals emerge in July or August, though those that overwinter may emerge earlier in the spring[8].

Defenses

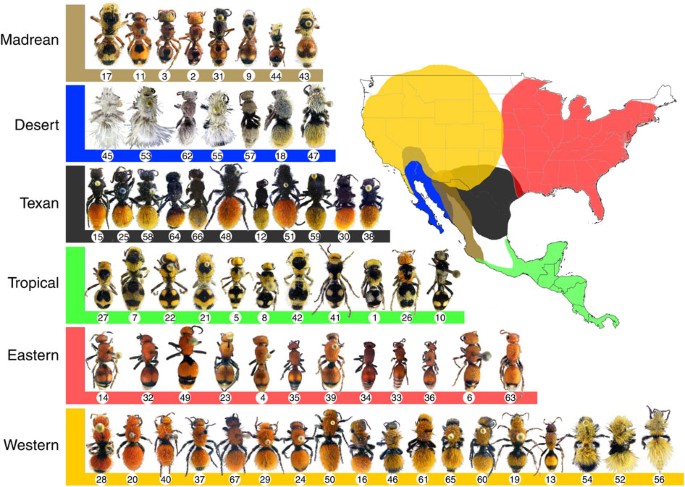

The Red Velvet Ant has several adaptations that serve as defenses against predators. Its most apparent defense is aposematic coloration—its bright red hairs contrasted with black markings make it a striking and easily recognizable insect. This warning coloration is especially significant in the context of North American Mutillidae (Velvet Ants), most of which participate in complex Müllerian mimicry rings.

Müllerian mimicry occurs when two or more well-defended species evolve to share similar warning signals, reinforcing avoidance behavior in predators. Velvet Ants in North America can be categorized into eight distinct mimicry rings, each corresponding to a geographic region [9]. For example, species in the eastern U.S., such as the Red Velvet Ant, typically exhibit fiery red and black coloration. In contrast, tropical Velvet Ants found in Central America tend to be black and yellow—mimicking the warning colors of bees and wasps. Desert-dwelling Velvet Ants are often pale or white in appearance, while populations in Texas may display coloration limited to the thorax. When researchers examined all 21 genera of Velvet Ants in North America, they found that only 15 out of 351 species did not fit into one of the eight mimicry rings[9]. This widespread mimicry system allows species to benefit from shared predator learning in their respective habitats, increasing their survival.

Aside from coloration, the primary defense of female Red Velvet Ants is evasion; they typically flee when threatened. If cornered, they may produce audible squeaking sounds as a further deterrent [5]. Their final line of defense is their modified ovipositor, which doubles as a powerful stinger. Although the venom of the Red Velvet Ant is approximately 25 times less toxic than that of a honeybee, its sting is notoriously painful, often lasting up to 30 minutes.While not dangerous to humans, the intensity of the pain has earned them the nickname "cow killers." However, Red Velvet Ants are unlikely to sting unless directly provoked, as their stinger is primarily used for egg-laying, and its use carries biological cost. In contrast, eusocial wasps and bees have disposable stingers and rely on a reproductive queen, which allows worker individuals to be more aggressive. Finally, Red Velvet Ants possess an exceptionally thick and durable exoskeleton, adding yet another layer of protection and making them difficult for predators to injure or consume.

References

[1] [11] [3] [5] [7] [4] [8] [6] [2] [10] [9]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 “Arthropod Museum, Dept. of Entomology, University of Arkansas,” May 26, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120526173101/http://www.uark.edu/ua/arthmuse/cowkil.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Velvet Ant.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/biological-control-information-center/beneficial-parasitoids/velvet-ant/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 iNaturalist. “Red Velvet Ant (GTM Research Reserve Arthropod Guide) · iNaturalist.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/278784.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “Red Velvet Ant or ‘Cow Killer,’” September 2, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110902230354/http://insects.tamu.edu/fieldguide/cimg344.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Missouri Department of Conservation. “Velvet Ants.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/velvet-ants.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 “Species Dasymutilla Occidentalis - Common Eastern Velvet Ant.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://bugguide.net/node/view/13126/data.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 “Red Velvet Ant; Cow Killer | Arthropod Museum.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://arthropod.uark.edu/red-velvet-ant-cow-killer/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Smith, Caleb. “Dasymutilla Occidentalis.” Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 20, 2025. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Dasymutilla_occidentalis/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Wilson, Joseph S., Kevin A. Williams, Matthew L. Forister, Carol D. von Dohlen, and James P. Pitts. “Repeated Evolution in Overlapping Mimicry Rings among North American Velvet Ants.” Nature Communications 3, no. 1 (December 11, 2012): 1272. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2275.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 “Velvet Ants: Flamboyant and Fuzzy with Extreme PPE | Natural History Museum.” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/velvet-ants-flamboyant-and-fuzzy-with-extreme-ppe.html.

- ↑ Field Guide to Common Texas Insects. “Red Velvet Ant or ‘Cow Killer.’” Accessed April 20, 2025. https://texasinsects.tamu.edu/red-velvet-ant-or-cow-killer/.