Diplopoda: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

== Reproduction and Life Cycle == | == Reproduction and Life Cycle == | ||

Male millipedes have sex organs, called gonopods, on their seventh body segment. The eighth leg pair is modified to transfer a sperm packet called a spermatophore to the vulva of a female millipede, which is located behind the second pair of legs. During mating, males will crawl onto the backs of females and stimulate them with their legs while producing a calming sound. If the female is uninterested, she will coil up to prevent the male from depositing his spermatophore. Gravid females | Male millipedes have sex organs, called gonopods, on their seventh body segment. The eighth leg pair is modified to transfer a sperm packet called a spermatophore to the vulva of a female millipede, which is located behind the second pair of legs. During mating, males will crawl onto the backs of females and stimulate them with their legs while producing a calming sound. If the female is uninterested, she will coil up to prevent the male from depositing his spermatophore. Gravid females burrow into warm soil, where they lay eggs and encapsulate them in their feces. The number of eggs per brood varies across species, ranging from tens to hundreds of eggs. Nymphs hatch from the eggs and usually have six body segments and three pairs of legs. As they outgrow their exoskeletons, they will retreat to a sheltered area to molt. Some species will burrow underground or build molting chambers out of dirt, while other species can produce silk and spin a web around themselves<ref name="Ohio"></ref>. Millipedes exhibit amorphic development, meaning that they grow more body segments each with a pair of legs after every molt. They will often eat their exoskeletons after they molt to recycle nutrients like calcium or protein. Millipedes can live for up to 10 years depending on the species<ref name="Tohono"></ref>. | ||

== Diet and Feeding Behaviors == | == Diet and Feeding Behaviors == | ||

Revision as of 17:54, 3 April 2025

| |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Subkingdom: | Bilateria |

| Infrakingdom: | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Myriapoda |

| Class: | Diplopoda |

Diplopods, more commonly known as millipedes, are long, segmented invertebrates belonging to the subphylum Myriapoda. The Latin meaning of the name Diplopoda, 'having double feet', refers to the distinctive features of millipedes, in which they possess two pairs of legs per body segment [3][4]. While their common name means 'thousand feet', most millipede species possess 47 to 197 pairs of legs[5]. However, in 2020, the first millipede species with over one thousand legs was discovered in Western Australia — Eumillipes persephone, with 1,306 legs[6]. There are currently around 12,000 described species and 16 orders within the class Diplopoda[7].

Characteristics and Morphology

Most millipedes are long and either cylindrical or flat in shape. However, pill millipedes, belonging to the family Glomeridae, are stout and resemble isopods and, in similar fashion, can roll into a ball when disturbed.[8]. Most millipede species have hard, calcareous exoskeletons that protect them from predators and large forces faced when burrowing in soil[9]. Millipedes may roll into a spiral as a defense mechanism, where their harder exoskeleton on the top of each of their body segments, or tergites, protect their legs and more vulnerable underside. Millipedes lack a waxy layer on their epicuticle, making them vulnerable to desiccation[10]. The size of millipedes vary greatly across different species, with the smaller species measuring at around 2 mm long and the largest species, Archispirostreptus gigas, growing up to 13 inches long[5].

Millipedes bear a head with one pair of antennae, a pair of simple eyes known as ocelli, and a mouth. Their mouths consist of an upper lip (labrum), a pair of mandibles, and a grinding plate (gnathochilarium). The rest of their bodies are made up of many segments, with the number of segments varying with species and age. The first segment connected to the head, called the collum, has no legs and is also present in their closest relative clade Pauropoda. The following three segments bear only one pair of legs. Succeeding segments bear two pairs of legs, while the final few segments bear no legs. The last segment, called the telson, has a pair of anal valves which can open to release feces from the millipedes' digestive tract[7][4]. Millipedes move fairly slowly compared to their centipede relatives belonging to the subphylum Chilopoda. They move their legs in a wave-like motion, referred to as metachronal locomotion. Their many legs can produce a surprising amount of force, necessary to direct themselves when burrowing[11]. The species Diopsiulus regressus exhibits a unique behavior of jumping; however, this behavior is an escape reaction rather than a locomotive strategy[12].

Many millipede species possess glands called ozopores that run along the length of their bodies and can release chemical compounds that may be toxic or repel certain parasitic or predatory organisms. The chemicals secreted vary across species and include, but are not limited to, hydrogen cyanide, p-benzoquinones, phenols, alkaloids, and terpenoids. Millipedes that bear ozopores often have bright aposematic coloring. Other species that do not secrete defensive chemicals may bear similar coloring patterns as a result of Mullerian mimicry[7][13]. While these secretions may be irritating or toxic to certain organisms, other organisms may use millipede secretions to their advantage. Black lemurs (Eulemur macaco) have been observed biting millipedes and rubbing their defensive secretions on their bodies. Research has shown that the lemurs may do this to repel insects such as mosquitoes, but the they also seem to enter an intoxicated state[14]. Other research shows that these defensive secretions may also attract predators such as dung beetles[15].

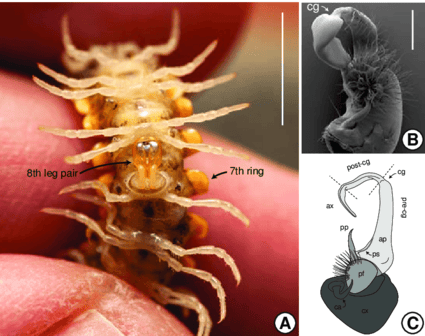

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Male millipedes have sex organs, called gonopods, on their seventh body segment. The eighth leg pair is modified to transfer a sperm packet called a spermatophore to the vulva of a female millipede, which is located behind the second pair of legs. During mating, males will crawl onto the backs of females and stimulate them with their legs while producing a calming sound. If the female is uninterested, she will coil up to prevent the male from depositing his spermatophore. Gravid females burrow into warm soil, where they lay eggs and encapsulate them in their feces. The number of eggs per brood varies across species, ranging from tens to hundreds of eggs. Nymphs hatch from the eggs and usually have six body segments and three pairs of legs. As they outgrow their exoskeletons, they will retreat to a sheltered area to molt. Some species will burrow underground or build molting chambers out of dirt, while other species can produce silk and spin a web around themselves[4]. Millipedes exhibit amorphic development, meaning that they grow more body segments each with a pair of legs after every molt. They will often eat their exoskeletons after they molt to recycle nutrients like calcium or protein. Millipedes can live for up to 10 years depending on the species[5].

Diet and Feeding Behaviors

Millipedes are primarily detritivores, consuming dead organic plant matter. They are selective feeders, choosing to feed on leaf litter with higher calcium contents and avoiding freshly fallen leaves or leaves with high polyphenol contents. Some species feed on live plants, and species with modified sucking mouth parts may consume plant sap, accumulating alkaloids in their tissues which may be used to produce their defensive secretions. Various species also eat fungi, algae, and lichen. Some diplopods are obligate coprophages, meaning they must eat their own feces. This may be due to the close relationship millipedes have with the microbiota within their guts that are necessary for the breakdown of cellulose and lignin[10][7].

Distribution

Millipedes are found in every continent except for Antarctica in a wide variety of habitats. They are particularly abundant in calcium-rich areas with high rainfall, particularly tropical and temperate forests. On average, tropical species are larger than temperate species. Some species spend their whole lives in the soil, while others reside in the leaf litter or other cryptozoic habitats like under rocks or decomposing tree bark. Some species are arboreal, meaning that they live on trees and branches, and these species are typically found in humid environments. Despite being vulnerable to desiccation, millipedes can also be found in arid climates, where they become active after rains and seek refuge by burrowing under vegetation or debris[10][7].

Ecological Functions

Diplopods play an important role in decomposition, as they are capable of fragmenting large dead plant materials, making them bioavailable for microbiota and therefore stimulating nutrient cycling. They are very important in boreal coniferous forests, as they have been found to consume up to 36% of the annual conifer litter in these regions[7]. Millipedes are also big contributors to the nutrient cycling of calcium, as research shows they process 15–20% of the calcium input into hardwood forest floors[10]. Their burrowing also helps loosen and aerate the soil, promoting a healthier soil ecosystem[4].

Millipedes serve as hosts to many parasites and mites; however, most mite interactions are examples of commensalism. Some mites and millipedes even have symbiotic relationships, with mites keeping the bodies of millipedes clean and receiving protection from predators in return[18].

Millipedes are not crop pests, but they may carry mites or diseases that could be harmful to crops if introduced into non-native habitats. They are not harmful to humans and do not transmit diseases to humans; however, their chemical secretions may cause blisters and are potentially toxic to pests. They do not cause harm to buildings and are considered more of a nuisance pest[19].

References

- ↑ Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). n.d. Diplopoda. https://itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=154409#null

- ↑ Kraft, S. & Pinto, L. (2024). Meet the Millipede. Pest Control Technology. https://www.pctonline.com/article/meet-the-millipede/

- ↑ Merriam-Webster. n.d. Diplopoda. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Diplopoda

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hennen, D. & Brown, J. n.d. Millipedes of Ohio Field Guide. Ohio Division of Wildlife. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://dam.assets.ohio.gov/image/upload/ohiodnr.gov/documents/wildlife/backyard-wildlife/Millipedes%20of%20Ohio%20Pub%205527.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tohono Chul. n.d. Millipede Facts. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://tohonochul.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Millipede_Facts_Worksheet.pdf

- ↑ Marek, P., et al. (2021). The first true millipede—1306 legs long. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02447-0

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Sierwald, P. & J.E. Bond. (2007). Current Status of the Myriapod Class Diplopoda (Millipedes):Taxonomic Diversity and Phylogeny. Annual Review of Entomology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17163800/

- ↑ Australian Museum. (2020). Pill Millipedes. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/centipedes/pill-millipedes/

- ↑ Borrel, B. (2004). Mechanical properties of calcified exoskeleton from the neotropical millipede, Nyssodesmus python. Journal of Insect Physiology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022191004001593

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Coleman, D.C., M.A. Callaham Jr., & D.A. Crossley Jr. (2017). Fundamentals of Soil Ecology - 3rd Edition. Academic Press.

- ↑ Garcia, A. et al. (2021). Fundamental understanding of millipede morphology and locomotion dynamics. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33007767/

- ↑ National Science and Technology Library. (1973). A jumping millipede. Nature. http://archive.nstl.gov.cn/Archives/browse.do?action=viewDetail&articleID=55ab74dff07239e2&navig=9565bcbb40dbfbe9&navigator=category&flag=byWord&subjectCode=null&searchfrom=null#:~:text=regressus%20Silvestri%20at%2064%20and%202%2C000%20frames%20s%20~l.%20The%20sudden%20body&text=1%20Side%20view%20of%20a%20jump%2C%20from,to%20left%2C%20of%20the%20millipede%20Diopsiulus%20regressus.

- ↑ Shear, W.A. (2015). The chemical defenses of millipedes (diplopoda): Biochemistry, physiology and ecology. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305197815001167

- ↑ Banerji, U. (2016). Lemurs Get High on Their Millipede Supply. Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/lemurs-get-high-on-their-millipede-supply

- ↑ Rodríguez‑López, M.E. et al. (2021). Attraction of Canthon vazquezae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) to Volatiles Released by Messicobolus magnificus (Diplopoda: Spirobolida). Journal or Insect Behavior. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10905-021-09785-x

- ↑ Marek, P. et al. (2014). A species catalog the millipede family Xystodesmidae (Diplopoda: Polydesmida). Virginia Museum of Natural History. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267810849_A_species_catalog_the_millipede_family_Xystodesmidae_Diplopoda_Polydesmida

- ↑ sofkeya. (2023). what are these little bugs on my millipedes and how can i get rid of them?[Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/millipedes/comments/14dnxn2/what_are_these_little_bugs_on_my_millipedes_and/

- ↑ Giant Millipedes. (2020). Millipede Health Problems. https://www.giantmillipedes.com/millipede-health-problems#:~:text=One%20thing%20you%20may%20notice,of%20things%20you%20could%20try.

- ↑ Rottler. n.d. Millipede. https://www.rottler.com/pests/occasional-invaders/millipede/