Entomopathogenic fungi: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

=Life Cycle= | =Life Cycle= | ||

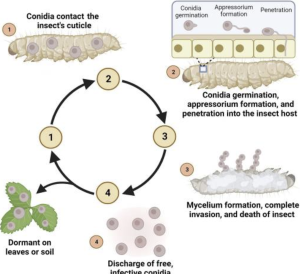

The fungi cycle begins with dormant fungi present on leaf, leaf litter, or soil ground. When an insect makes contact with this fungus, it attaches to the host organism's cuticle, or outside layer, preparing itself for penetration of the host. The next step involves germination of the conidia (asexual, non-motile spores) and the formation of the appressorium, which is almost like a peg produced by the conidia that can pierce the outer layer of the host organism. Once inside, step 3 begins and the hyphae begin to develop inside the host. Cell numbers rapidly multiply within the hemocoel (internal 'blood' and organs of the insect) until the hyphae grow enough to kill the organism. The final stage is fungal sporulation. Once the spores are developed, they get dispersed from the host organism. Some say this process could be more specific | The fungi cycle begins with dormant fungi present on leaf, leaf litter, or soil ground. When an insect makes contact with this fungus, it attaches to the host organism's cuticle, or outside layer, preparing itself for penetration of the host. The next step involves germination of the conidia (asexual, non-motile spores) and the formation of the appressorium, which is almost like a peg produced by the conidia that can pierce the outer layer of the host organism. Once inside, step 3 begins and the hyphae begin to develop inside the host. Cell numbers rapidly multiply within the hemocoel (internal 'blood' and organs of the insect) until the hyphae grow enough to kill the organism. The final stage is fungal sporulation. Once the spores are developed, they get dispersed from the host organism. Some say this process could be more specific, spliting 4 steps into 6 steps, but the process remains the same. | ||

Revision as of 15:17, 2 April 2025

Entomopathogenic Fungi are parasitic microorganisms that infect insect hosts in many different ecosystems. They serve as a means to control insect populations and in doing so, prevents the overgrowth of insect organisms in soil environments and enhanced biodiversity. When infected, the insects eventually die off promoting the growth of soil microorganisms. They are then an energy source for microorganisms and contribute to nutrient cycling and promote plant growth. Entomopathogenic Fungi can be referred to as "EPF" and are responsible for over 60% of insect deaths in nature. [3]

Life Cycle

The fungi cycle begins with dormant fungi present on leaf, leaf litter, or soil ground. When an insect makes contact with this fungus, it attaches to the host organism's cuticle, or outside layer, preparing itself for penetration of the host. The next step involves germination of the conidia (asexual, non-motile spores) and the formation of the appressorium, which is almost like a peg produced by the conidia that can pierce the outer layer of the host organism. Once inside, step 3 begins and the hyphae begin to develop inside the host. Cell numbers rapidly multiply within the hemocoel (internal 'blood' and organs of the insect) until the hyphae grow enough to kill the organism. The final stage is fungal sporulation. Once the spores are developed, they get dispersed from the host organism. Some say this process could be more specific, spliting 4 steps into 6 steps, but the process remains the same.

Soil Benefits

EMF has been used as a means to control pest and insect populations for generations due to its biopesticidal properties. There are 1600 known species across 90 genera but the primary products produced from EMF derive from a much smaller selection, at least 12 species, since they are easier to mass produce and they are more efficient. The most widely commercially produced fungi come from species within the Beauveria, Metarhizium, Lecanicillium and Isaria generas. [5] These developments and practices help to introduce a new method of pest and population control in soil environments that avoid the use of highly processed pesticides.

EPF can promote soil aggregation by producing sticky protiens like glomalin and glycoprotien polysaccharides. These substances are also helpful in retaining water, nutrients, and carbon. All of these factors contribute to enhanced plant growth. Regarding nutrient recycling, it has been found that EPFs are able to decompose organic matter with a lower metabolic nutrient demand as well as being able to utilize a wider array of enzymes in the process. As a result, EPFs can more effectively decompose "sugars, organic acids, amino acids... cellulose, pectin, lignin, lignocellulose, chitin, starch... hydrocarbons, pesticides, and other xenobiotics" (Murindangabo). [4] (Still editing)

References

[1] Kay, A.,(2017). Cricket? with Entomopathogenic fungus [Photograph]. flickr.com. https://www.flickr.com/photos/andreaskay/44264582075/in/photostream/

[2] Liu, Y., Yang, Y. & Wang, B. Entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae play roles of maize (Zea mays) growth promoter. Sci Rep 12, 15706 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19899-7

[3] Ma M, Luo J, Li C, Eleftherianos I, Zhang W and Xu L (2024) A life-and-death struggle: interaction of insects with entomopathogenic fungi across various infection stages. Front. Immunol. 14:1329843. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1329843

[4] Murindangabo, Y. T., Kopecký, M., Perná, K., Konvalina, P., Bohatá, A., Kavková, M., & Nguyen, T. G. (2024). Relevance of entomopathogenic fungi in soil-plant systems. Plant and Soil, 495(1-2), 287+. http://dx.doi.org.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/10.1007/s11104-023-06325-8

[5] Vega, Fernando E., et al. “Fungal Entomopathogens: New Insights on Their Ecology.” Fungal Ecology, vol. 2, no. 4, 2009, pp. 149–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2009.05.001.

[6] Zhang, W., Chen, X., Eleftherianos, I., Mohamed, A., Bastin, A., & Keyhani, N. O. (2024). Cross-talk between immunity and behavior: insights from entomopathogenic fungi and their insect hosts. FEMS microbiology reviews, 48(1), fuae003. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuae003