Gastropoda: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Partula.jpg|thumb|''Partula taeniata, a tree snail from Moorea, French Polynesia.''[https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/gastropoda.php]] | |||

== Background & Life History == | |||

The class gastropoda takes its name from the Greek words "gaster" meaning gastric and "pous" meaning foot, referring to their guts located just above their foot. They have a long and rich fossil record from the Early Cambrian that shows periodic extinctions of subclades, followed by diversification of new groups. The Class Gastropoda includes snails, [[slugs]], limpets, and sea hares. Gastropods have been prominent throughout paleobiologic and biological historical studies, and have served as study [[organisms]] in numerous evolutionary, biomechanical, ecological, physiological, and behavioral investigations [5]. | |||

Gastropods are mainly dioecious yet some forms are hermaphroditic. Hermaphroditic forms exchange bundles of sperm to avoid self-fertilization; copulation may be complex and in some species ends with each individual sending a sperm-containing dart into the tissues of the other [6]. Marine species have veliger larvae. Most aquatic gastropods are benthic and mainly epifaunal but some are planktonic [5]. | |||

Gastropods have a | == Ecology & Habitat == | ||

Gastropods live in every conceivable habitat on Earth, with worldwide distribution. They have adapted to almost every kind of existence on earth and colonized nearly every available medium. They occupy all marine habitats ranging from the deepest ocean basins to the supralittoral, as well as freshwater habitats, and other inland aquatic habitats including salt lakes [3]. They are also the only terrestrial mollusks to be found in virtually all habitats ranging from high mountains to deserts and rainforest, and from the tropics to high latitudes. Some of the more familiar and better-known gastropods are terrestrial gastropods (the land snails and slugs). Some live in freshwater, but the majority of gastropods live in a marine environment. In habitats where there is not enough calcium carbonate to build a solid shell, such as some acidic soils on land, there are still various species of slugs, and also some snails with a thin translucent shell, mostly or entirely composed of the protein conchiolin [4]. | |||

Their feeding habits are extremely varied, although most species make use of a radula (structure of tiny teeth) in some aspect of their feeding behavior. They include grazers, browsers, suspension feeders, scavengers, [[detritivores]], and carnivores. Carnivory in some taxa may simply involve grazing on colonial [[animals]], while others engage in hunting their prey. Some gastropod carnivores drill holes in their shelled prey. This method of entry has been acquired independently in several groups, as is also the case with carnivory itself. Some gastropods feed suctorially and have lost the radula [5]. | |||

Torsion in gastropods has the unfortunate result | ==Diversity== | ||

Gastropoda are one of the most diverse class of animals, in both form and habitat, falling only second behind [[insects]]. They are the most abundant class in number and species of the phylum Mollusca. With more than 62,000 described living species, they comprise about 80% of all living mollusks. Fossil records show around 15,000 species while estimates of current day species ranges from 40,000 to 150,000 depending on the study cited. The diversity of gastropods can be seen in their anatomy, habits, shell morphology, and habitat. They can be found in nearly every habitat found on Earth, being the only mollusks to contain terrestrial species [5]. Few marine gastropod species can live in the abyssal zone or the continental shelf; marine gastropod diversity is highest at the continental slope and the continental rise. | |||

== Morphology == | |||

Gastropods are characterized by having a true head, an unsegmented body, a broad, flat foot and the possession of a single, often coiled shell, although this is lost in some slug groups. When present, the shell is in one piece and spirally coiled. The uppermost part of the shell is formed from the larval shell (the protoconch). The shell is partly or entirely lost in the juveniles or adults of some groups, with total loss occurring in several groups of land slugs and sea slugs. All fossil gastropods and most modern ones have a coiled shell, which is all that remains for the identification of fossil forms, while the identification of modern species is based largely on soft body parts [2]. The mantle cavity and visceral mass undergo torsion. Torsion takes place during the veliger stage, usually very rapidly. Veligers are at first bilaterally symmetric, but torsion destroys this pattern and results in an asymmetric adult. Some species reverse torsion ("detorsion"), but evidence of having passed through a twisted phase can be seen in the anatomy of these forms [6]. Torsion in gastropods has the unfortunate result of waste being expelled from the gut and nephridia near the gills. A variety of morphological and physiological adaptations have arisen to separate water used for respiration from water bearing waste products [6]. There is also usually a well-developed radula. They have a muscular foot which is used for "creeping" locomotion in most species, while in some it is modified for swimming or burrowing. The foot is usually rather large and typically bears an operculum that seals the shell opening (aperture) when the head-foot is retracted into the shell. They move by producing a mucus lubricant under the flat ventral surface of the foot and a series of muscular contractions allow them to “slide” across the substrate. Most gastropods have a well-developed head that includes eyes (short to long stalks), 1-2 pairs of tentacles, and a concentration of nervous tissue (ganglion) [6]. The mantle edge in some taxa is extended anteriorly to form an inhalant siphon and this is sometimes associated with an elongation of the shell opening (aperture) [5]. The nervous and circulatory systems are well developed with the concentration of nerve ganglia being a common evolutionary theme. Many snails have an [[operculum]], a horny plate that seals the opening when the snail's body is drawn into the shell. Externally, gastropods appear to be bilaterally symmetrical, however, they are one of the most successful clades of asymmetric organisms known [5] . | |||

[[File:Shell morph.jpg|caption]] | |||

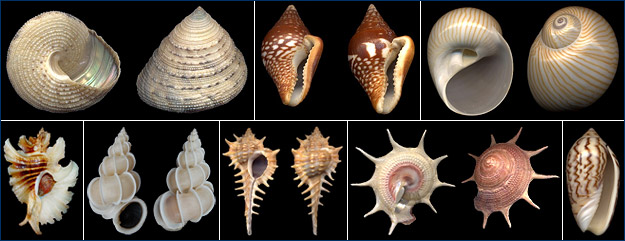

''Variation in shell morphology in some marine gastropods. [3] | |||

Gastropod | [[File:Gastropod Morphology.jpg]] | ||

== | ==Ecological Importance== | ||

Due to their abundance and [[diversity]], gastropoda play important roles in ecosystem functions by serving as prey for many other species and promoting the [[decomposition]] of dead plant/ vegetable matter and the subsequent recycling of nutrients [7]. They eat very low on the food web, as most land snails will consume rotting vegetation like moist leaf litter, fungi, or even eat [[soil]] directly. Indirectly, they are of great importance by furnishing food for many fish and other animals. Snails unfortunately, can be of economic importance, as they can vector parasites that risk the health of humans and animals | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 32: | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

[1] Holthuis, B.V. (1995): ''Evolution between marine and freshwater habitats: a case study of the gastropod suborder Neritopsina.'' Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington | |||

[2] Allaby, M. 2020. A Dictionary of Zoology. Oxford University Press, Incorporated, Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM. | |||

[3] “The Gastropoda.” Ucmp.berkeley.edu, 1999, ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/gastropoda.php. | |||

[4] “Gastropoda.” Wikipedia, 29 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastropoda. | |||

[5] “Mollusca: Gastropoda.” Ucmp.berkeley.edu, ucmp.berkeley.edu/mollusca/mollusca/gastropoda/gastropoda.html. | |||

[6] Myers, P., and J. B. Burch. 2001. Gastropoda. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Gastropoda/. | |||

[7] P. Bloch, C. 2012. Why Snails? How Gastropods Improve Our Understanding of Ecological Disturbance. Bridgewater Review Vol. 31. | |||

Latest revision as of 10:37, 12 May 2023

Background & Life History

The class gastropoda takes its name from the Greek words "gaster" meaning gastric and "pous" meaning foot, referring to their guts located just above their foot. They have a long and rich fossil record from the Early Cambrian that shows periodic extinctions of subclades, followed by diversification of new groups. The Class Gastropoda includes snails, slugs, limpets, and sea hares. Gastropods have been prominent throughout paleobiologic and biological historical studies, and have served as study organisms in numerous evolutionary, biomechanical, ecological, physiological, and behavioral investigations [5].

Gastropods are mainly dioecious yet some forms are hermaphroditic. Hermaphroditic forms exchange bundles of sperm to avoid self-fertilization; copulation may be complex and in some species ends with each individual sending a sperm-containing dart into the tissues of the other [6]. Marine species have veliger larvae. Most aquatic gastropods are benthic and mainly epifaunal but some are planktonic [5].

Ecology & Habitat

Gastropods live in every conceivable habitat on Earth, with worldwide distribution. They have adapted to almost every kind of existence on earth and colonized nearly every available medium. They occupy all marine habitats ranging from the deepest ocean basins to the supralittoral, as well as freshwater habitats, and other inland aquatic habitats including salt lakes [3]. They are also the only terrestrial mollusks to be found in virtually all habitats ranging from high mountains to deserts and rainforest, and from the tropics to high latitudes. Some of the more familiar and better-known gastropods are terrestrial gastropods (the land snails and slugs). Some live in freshwater, but the majority of gastropods live in a marine environment. In habitats where there is not enough calcium carbonate to build a solid shell, such as some acidic soils on land, there are still various species of slugs, and also some snails with a thin translucent shell, mostly or entirely composed of the protein conchiolin [4].

Their feeding habits are extremely varied, although most species make use of a radula (structure of tiny teeth) in some aspect of their feeding behavior. They include grazers, browsers, suspension feeders, scavengers, detritivores, and carnivores. Carnivory in some taxa may simply involve grazing on colonial animals, while others engage in hunting their prey. Some gastropod carnivores drill holes in their shelled prey. This method of entry has been acquired independently in several groups, as is also the case with carnivory itself. Some gastropods feed suctorially and have lost the radula [5].

Diversity

Gastropoda are one of the most diverse class of animals, in both form and habitat, falling only second behind insects. They are the most abundant class in number and species of the phylum Mollusca. With more than 62,000 described living species, they comprise about 80% of all living mollusks. Fossil records show around 15,000 species while estimates of current day species ranges from 40,000 to 150,000 depending on the study cited. The diversity of gastropods can be seen in their anatomy, habits, shell morphology, and habitat. They can be found in nearly every habitat found on Earth, being the only mollusks to contain terrestrial species [5]. Few marine gastropod species can live in the abyssal zone or the continental shelf; marine gastropod diversity is highest at the continental slope and the continental rise.

Morphology

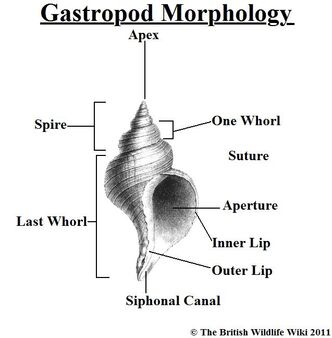

Gastropods are characterized by having a true head, an unsegmented body, a broad, flat foot and the possession of a single, often coiled shell, although this is lost in some slug groups. When present, the shell is in one piece and spirally coiled. The uppermost part of the shell is formed from the larval shell (the protoconch). The shell is partly or entirely lost in the juveniles or adults of some groups, with total loss occurring in several groups of land slugs and sea slugs. All fossil gastropods and most modern ones have a coiled shell, which is all that remains for the identification of fossil forms, while the identification of modern species is based largely on soft body parts [2]. The mantle cavity and visceral mass undergo torsion. Torsion takes place during the veliger stage, usually very rapidly. Veligers are at first bilaterally symmetric, but torsion destroys this pattern and results in an asymmetric adult. Some species reverse torsion ("detorsion"), but evidence of having passed through a twisted phase can be seen in the anatomy of these forms [6]. Torsion in gastropods has the unfortunate result of waste being expelled from the gut and nephridia near the gills. A variety of morphological and physiological adaptations have arisen to separate water used for respiration from water bearing waste products [6]. There is also usually a well-developed radula. They have a muscular foot which is used for "creeping" locomotion in most species, while in some it is modified for swimming or burrowing. The foot is usually rather large and typically bears an operculum that seals the shell opening (aperture) when the head-foot is retracted into the shell. They move by producing a mucus lubricant under the flat ventral surface of the foot and a series of muscular contractions allow them to “slide” across the substrate. Most gastropods have a well-developed head that includes eyes (short to long stalks), 1-2 pairs of tentacles, and a concentration of nervous tissue (ganglion) [6]. The mantle edge in some taxa is extended anteriorly to form an inhalant siphon and this is sometimes associated with an elongation of the shell opening (aperture) [5]. The nervous and circulatory systems are well developed with the concentration of nerve ganglia being a common evolutionary theme. Many snails have an operculum, a horny plate that seals the opening when the snail's body is drawn into the shell. Externally, gastropods appear to be bilaterally symmetrical, however, they are one of the most successful clades of asymmetric organisms known [5] .

Variation in shell morphology in some marine gastropods. [3]

Ecological Importance

Due to their abundance and diversity, gastropoda play important roles in ecosystem functions by serving as prey for many other species and promoting the decomposition of dead plant/ vegetable matter and the subsequent recycling of nutrients [7]. They eat very low on the food web, as most land snails will consume rotting vegetation like moist leaf litter, fungi, or even eat soil directly. Indirectly, they are of great importance by furnishing food for many fish and other animals. Snails unfortunately, can be of economic importance, as they can vector parasites that risk the health of humans and animals

References

[1] Holthuis, B.V. (1995): Evolution between marine and freshwater habitats: a case study of the gastropod suborder Neritopsina. Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington

[2] Allaby, M. 2020. A Dictionary of Zoology. Oxford University Press, Incorporated, Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM.

[3] “The Gastropoda.” Ucmp.berkeley.edu, 1999, ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/gastropoda.php.

[4] “Gastropoda.” Wikipedia, 29 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastropoda.

[5] “Mollusca: Gastropoda.” Ucmp.berkeley.edu, ucmp.berkeley.edu/mollusca/mollusca/gastropoda/gastropoda.html.

[6] Myers, P., and J. B. Burch. 2001. Gastropoda. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Gastropoda/.

[7] P. Bloch, C. 2012. Why Snails? How Gastropods Improve Our Understanding of Ecological Disturbance. Bridgewater Review Vol. 31.