Acari: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

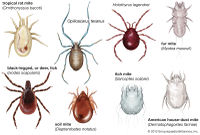

Acari are a taxon of the Arachnida class and are the most abundant as well as the most diverse of the arachnids that include animals such as [[mites]] and ticks. The existence of these creatures has been dated as far back as 400 million years ago to the early Devonian Period, making them the oldest terrestrial [[animals]]. Due to their immense diversity, they vary heavily in terms of size,shape, and structure. The species of Acari are relatively small in size being as small as the human follicle mite at around 0.1 mm and as large as ticks or the Red Velvet mite which can be as large as 10 mm. [1] As of 1999, over 50,000 species of Acari have been documented and it is estimated that around 1 million more have yet to be discovered. [2] | [[File:Rust_Mite,_Aceria_anthocoptes.jpg|200px|thumb|right]]Acari are a taxon of the Arachnida class and are the most abundant, as well as, the most diverse of the arachnids that include animals such as [[mites]] and ticks. The existence of these creatures has been dated as far back as 400 million years ago to the early Devonian Period, making them the oldest terrestrial [[animals]]. Due to their immense [[diversity]], they vary heavily in terms of size, shape, and structure. The species of Acari are relatively small in size, being as small as the human follicle mite at around 0.1 mm and as large as ticks or the Red Velvet mite which can be as large as 10 mm. [1] As of 1999, over 50,000 species of Acari have been documented and it is estimated that around 1 million more have yet to be discovered. [2] | ||

== Habitat and Distribution == | == Habitat and Distribution == | ||

Because of their vast abundance and diversity, acari are distributed to essentially all locations of the world. Their presence has been recorded as high up as the slopes of Mt. Everest, as deep as 3 miles below the surface of the ocean, and even on the continent of Antarctica. These minuscule animals can be found in almost any particular habitat from the hot springs of Yellowstone to the seemingly uninhabitable Saharan desert. Despite most of the species being defined as free-living, some species of Acari are | Because of their vast abundance and diversity, acari are distributed to essentially all locations of the world. Their presence has been recorded as high up as the slopes of Mt. Everest, as deep as 3 miles below the surface of the ocean, and even on the continent of Antarctica. These minuscule animals can be found in almost any particular habitat from the hot springs of Yellowstone to the seemingly uninhabitable Saharan desert. In upper layers of the [[soil]], as many as 50,000-250,000 of these [[organisms]] can be found in one square meter.[5] Despite most of the species being defined as free-living, some species of Acari also engage in parasitism of other animals. [3] | ||

== Morphology & Anatomy == | |||

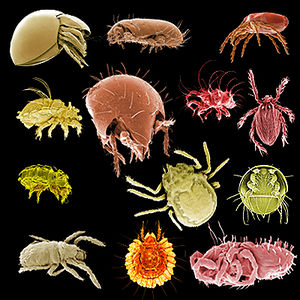

[[File:54894-004-8C1BBFF7 (1).jpg|200px|thumb|right]] Although being more closely related to spiders, acari also share several similarities with [[insects]]. When it comes to adaptability to both terrestrial and aquatic environments, both excel. Species of acari also enjoy the benefits of jointed legs and chitinous exoskeletons just like that of insects. That being said, they still exhibit more similarities to spiders like that of their piercing mouthparts as well as other features like an open circulatory system, ventral nerve chord, alimentary canal, and striated muscles. As much as they have in common with both insects and [[arthropods]], acari have their own particular features as well as a lack of qualities that are seen in the other two discussed previously. For example, acarids do not possess mandibles or antenna. The acari body is structured and divided into two regions: the gnathosoma which contains the head and mouth and the idiosoma which is where the legs, genital & anal openings, and sensory structures can be found. [4] Acarids also have an outer cuticle on their bodies which allows them to absorb water from the air in order to avoid desiccation. The bodies of acarids are also covered in setae which basically work as sensory receptors. [3] | |||

== Reproduction & Life Cycle == | |||

A separation of sexes exists among all acarids, with most species laying eggs although, there are some parasitic species that hatch the eggs inside the mother and the offspring is then born alive. It is also possible for some species to reproduce via parthenogenesis. The majority of the species, except those of the [[prostigmata]] and oribatada, endure a fairly simple 4-staged life cycle despite there being slight variations in the same cycle among different species. The inception of the life cycle begins with acarids as [[hexapod]] larva, continues on to the protonymph stage, the deutonymph stage, and ends with the tritonymph phase. [3] | |||

== Ecological Niches == | |||

Although the roles that acarids play in overall soil [[ecology]] are small in comparison to other living organisms, they still have roles to play nonetheless. Some of the species aid in the construction of [[humus]] which allows many other [[soil organisms]] to exist. Acarids are also vital for what they do for mineral turnover, vegetation succession, and even [[decomposition]].[5] | |||

[[File:2AcariF.jpg|300px|thumb]] | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 9: | Line 19: | ||

2. Walter, D.E.; Proctor, H.C. (1999). ''Mites: Ecology, Evolution, and Behaviour.'' University of NSW Press, Sydney and CABI, Wallingford. ISBN 978-0-86840-529-2 | 2. Walter, D.E.; Proctor, H.C. (1999). ''Mites: Ecology, Evolution, and Behaviour.'' University of NSW Press, Sydney and CABI, Wallingford. ISBN 978-0-86840-529-2 | ||

3. Wilson, Nixon A., (2011, Nov. 22) ''Acarid-Arachnid'' https://www.britannica.com/animal/acarid | |||

4. Dhooria M.S. (2016) Morphology and Anatomy of Acari. In: Fundamentals of Applied Acarology. Springer, Singapore | |||

5. Hoy M.A. (2008) Soil Mites (Acari: [[Oribatida]] and Others). In: Capinera J.L. (eds) Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer, Dordrecht | |||

Latest revision as of 08:50, 30 April 2021

Overview

Acari are a taxon of the Arachnida class and are the most abundant, as well as, the most diverse of the arachnids that include animals such as mites and ticks. The existence of these creatures has been dated as far back as 400 million years ago to the early Devonian Period, making them the oldest terrestrial animals. Due to their immense diversity, they vary heavily in terms of size, shape, and structure. The species of Acari are relatively small in size, being as small as the human follicle mite at around 0.1 mm and as large as ticks or the Red Velvet mite which can be as large as 10 mm. [1] As of 1999, over 50,000 species of Acari have been documented and it is estimated that around 1 million more have yet to be discovered. [2]

Habitat and Distribution

Because of their vast abundance and diversity, acari are distributed to essentially all locations of the world. Their presence has been recorded as high up as the slopes of Mt. Everest, as deep as 3 miles below the surface of the ocean, and even on the continent of Antarctica. These minuscule animals can be found in almost any particular habitat from the hot springs of Yellowstone to the seemingly uninhabitable Saharan desert. In upper layers of the soil, as many as 50,000-250,000 of these organisms can be found in one square meter.[5] Despite most of the species being defined as free-living, some species of Acari also engage in parasitism of other animals. [3]

Morphology & Anatomy

Although being more closely related to spiders, acari also share several similarities with insects. When it comes to adaptability to both terrestrial and aquatic environments, both excel. Species of acari also enjoy the benefits of jointed legs and chitinous exoskeletons just like that of insects. That being said, they still exhibit more similarities to spiders like that of their piercing mouthparts as well as other features like an open circulatory system, ventral nerve chord, alimentary canal, and striated muscles. As much as they have in common with both insects and arthropods, acari have their own particular features as well as a lack of qualities that are seen in the other two discussed previously. For example, acarids do not possess mandibles or antenna. The acari body is structured and divided into two regions: the gnathosoma which contains the head and mouth and the idiosoma which is where the legs, genital & anal openings, and sensory structures can be found. [4] Acarids also have an outer cuticle on their bodies which allows them to absorb water from the air in order to avoid desiccation. The bodies of acarids are also covered in setae which basically work as sensory receptors. [3]

Reproduction & Life Cycle

A separation of sexes exists among all acarids, with most species laying eggs although, there are some parasitic species that hatch the eggs inside the mother and the offspring is then born alive. It is also possible for some species to reproduce via parthenogenesis. The majority of the species, except those of the prostigmata and oribatada, endure a fairly simple 4-staged life cycle despite there being slight variations in the same cycle among different species. The inception of the life cycle begins with acarids as hexapod larva, continues on to the protonymph stage, the deutonymph stage, and ends with the tritonymph phase. [3]

Ecological Niches

Although the roles that acarids play in overall soil ecology are small in comparison to other living organisms, they still have roles to play nonetheless. Some of the species aid in the construction of humus which allows many other soil organisms to exist. Acarids are also vital for what they do for mineral turnover, vegetation succession, and even decomposition.[5]

References

1. Walter, David Evans; Krantz, Gerald; Lindquist, Evert (December 13, 1996) "Acari. The Mites. Tree of Life Web Project.

2. Walter, D.E.; Proctor, H.C. (1999). Mites: Ecology, Evolution, and Behaviour. University of NSW Press, Sydney and CABI, Wallingford. ISBN 978-0-86840-529-2

3. Wilson, Nixon A., (2011, Nov. 22) Acarid-Arachnid https://www.britannica.com/animal/acarid

4. Dhooria M.S. (2016) Morphology and Anatomy of Acari. In: Fundamentals of Applied Acarology. Springer, Singapore

5. Hoy M.A. (2008) Soil Mites (Acari: Oribatida and Others). In: Capinera J.L. (eds) Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer, Dordrecht