Rhamnus cathartica (Common Buckthorn)

| |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rhamnaceae |

| Genus: | Rhamnus L |

| Species: | R. cathartica L. |

| Source: United States Department of Agriculture[1] | |

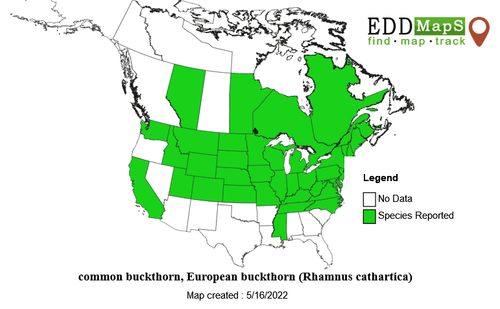

Rhamnus cathartica also known as Common Buckthorn, Purging buckthorn, European buckthorn, or buckthorn is a plant native to calcareous soils throughout England, into Scandaninavia and across Russia into western Asia, as well as being found as far south as Morocco and Algeria.[2] Buckthorn was introduced to the United States as early as the 1800s as an ornamental shrub by, and is now common across many of the lower 48 states as an invasive species.[3]

Description

Rhamnus cathartica is a medium to large sized woody plant..[4] Twigs end in sharp spines, and are usually dark and unlined.[4] Leaves are elliptic, hairless, and finetoothed, usually 1 1/2" to 2".[4] Plant usually flowers from May to June, small, greenish, clustered blooms. Fruits are produced in numerous drupes, with berries which turn from green to black as they ripen.[3] Although leaves usually exhibit opposite growth form, older growth may display alternate.[4]

Ecology

Buckthorn is a relatively fast-growing species, able to grow both in shady and open conditions.[3] Germination occurs in the autumn and spring in Great Britain, and mid- to late summer in some areas of the US, such as Minnesota.[3] R. cathartica produces fruit, at a rate which is often called aggressive, aiding in a high reproduction rate.[3] Buckthorn can grow in a range of soil types, from wetlands to drier oak forests.[3] It is a perennial plant and persists for many growing seasons, and it has extremely vigorous vegetative regeneration, able to regrow from very little material.[5]

R. cathartica is also a possible host for oat crown rust, a disease which affects oat seed farming, making it of interest for United States agriculture.[2]

Extremely similar to the relationship between monarch butterflies and plants of the Asclepiadaceae (milkweed) family, common buckthorn acts as an important host plant to the brimstone butterfly (Gonepteryx rhamni) in its native ranges in Europe.[6]

Allelopathy

R. cathartica contains a number of secondary compounds, present in both the fruit, leaves, root exudates, and other tissue of the plant[5] A specifically noted compound is that of emodin, which can impact germination of other plant seeds.[3] Emodin is present both in the root exudate of R. cathartica and in the fruit; due to the fact that the drupes often fall beneath the parent tree, both have a significant impact on germination. The presence of emodin also may contribute to the purgative effects of R. cathartica fruit, meaning that those unripe fruits which any animal may ingest will cause either regurgitation or very quick passing of the fruit.[3] This is significant as birds readily eat the fruit available.

Impact as an Invasive Species

Since its introduction to the United States in the 1800s, R. cathartica has established itself in much of the lower 48 states.[7] It has significant impact as an invasive species due to its allelopathic compounds, as discussed. In addition to this, buckthorn has an advantage when it comes phenology: extended leaf phenology. Buckthorn tends to flush out much earlier than native plants in its introduced range, allowing it to have photosynthetic advantage and to shade out native understory plants in the process, encouraging the establishment of a monoculture.[3] Additionally, the drupes on the shrub remain long past other native berries, providing a singular food source for birds which disperse the seeds as a result.[3]

Another advantage is the preference that insects and mammalian herbivores have for native plants over R. cathartica in North America.[3] White-tailed deer, a significant herbivorous population, preferentially eat native plants due to the fact that R. cathartica causes them some illness, resulting in increased herbivorous pressure on those native plants. This also applies to small mammals which forage in the relevant environments. The presence of thick monospecific thickets which R. cathartica form tends to encourage small mammal foraging, due to an increase in available refuge; this limits the germination of native trees or other highly foraged plants.[8]

The result of the success of R. cathartica as a competitor means that when introduced in an area, buckthorn tends to form dense monospecific thickets which exclude any native competitors and often reducing understory plants to a minimum.[3] With monospecific thickets such as these, there is also the alteration of nutrient cycling, as the leaves of buckthorn are extremely high in Nitrogen. The change in litter types has significant impact on the soil ecology as it will rapidly increase high-N litter pools and then rapidly decrease them as longer lasting leaf litter is eradicated.[3] When this is combined with invasive earthworms such as L. terrestris the alteration of soil ecology in an area is notable, where quickly decomposing leaves and the high loss of detritus in the presence of invasive earthworms intersect and create rapidly cycling nutrient pools.

The allelopathic nature of R. cathartica also falls under the hypothesis of the novel weapons hypothesis; the hypothesis that non-native plants have competitive traits which native plants in the introduced range do not have a defense against.[9] The root exudates and secondary compounds of R. cathartica are hypothesized to inhibit not only the growth and germination of competitor plants, but also possibly the mutualist fungi which other plants form symbiosis with. As has been established, buckthorn contains emodin, a powerful allelochemical; in some cases this has been found to impact the mutualisms of other plants. The root exudates of R. cathartica were found to reduce arbuscular and vesicular colinization in Ulmus sp. despite both plants employing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in their mutualist relationships.[9] It is possible that there are other native competitors with fungal mutualisms which R. cathartica may indirectly degrade due to its allelopathy.

References

- ↑ "Rhamnus Cathartica Plant Profile", USDA "USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service", USDA, n.d.. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 O. W. Archibold, D. Brooks, L. Delanoy, "An Investigation of the Invasive Shrub European Buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica L., near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan", The Canadian Field-Naturalist. October 1997. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Kathleen S. Knight, Jessica S. Kurylo, Anton G. Endress, J. Ryan Stewart, Peter B. Reich, "Ecology and ecosystem impacts of common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica): a review", Biological Invasions (2007) 9:925-937. 13 February 2007. doi: 10.1007/s10530-007-9091-3. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 George A. Petrides, "The Peterson Field Guide Series: A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs", Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1986. ISBN: 0-395-17579 "

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Scott Seltzner, Thomas L. Eddy. "Allelopathy in Rhamnus cathartica, European Buckthorn". The Michigan Botanist. 2003. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ David Gutiérrez, Chris D. Thomas, "Marginal range expansion in a host-limited butterfly species Gonepteryx rhamni" Ecological Entomology (2000) 25, 165-170. 25 December 2001. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 EDDMapS. 2022. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed May 16, 2022.

- ↑ Ryan M. Utz, Alysha Slater, Hannah R. Rosche, Walter P. Carson. "Do dense layers of invasive plants elevate the foragingintensity of small mammals in temperate deciduous forests? A case study from Pennsylvania, USA". NeoBiota 56: 73–88 (2020) doi: 10.3897/neobiota.56.4958. Retrieved 5/16/2022.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pinzone, P., Potts, D., Pettibone, G. et al. "Do novel weapons that degrade mycorrhizal mutualisms promote species invasion?". Plant Ecol 219, 539–548 (2018). https://doi-org.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/10.1007/s11258-018-0816-4. Retrieved 5/16/2022.