Planaria

Introduction

Planaria, or flatworms, which occupy the order Tricladida within the phylum Platyhelminthes, are commonly inhabitants of freshwater sources such as streams or ponds, but some are terrestrial in deep soils [1]. These complex organisms are known to be scavengers, predators, and in many cases parasitic. Planarians such as Schmidtea mediterranea are known for their remarkable ability to regenerate from pluripotent stem cells scattered throughout their bodies [2]. These adult stem cells, also known as neoblasts, allow planarians to reproduce asexually as well as simply regenerating their entire body from a fragment roughly 1/279 the size of the original worm [7]. These model organisms are medically and scientifically important, as understanding the process of regeneration may carry incredible value to advanced technologies.

Anatomy

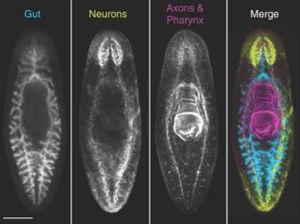

Planarians are triploblastic, involving all three germ layers (ecto-, meso-. and endoderm) and an organized nervous system composed of two anterior cephalic ganglia and two parallel nerve chords that run ventrally along the length of the body [9]. They also contain two photoreceptors which are connected to the nervous system by axons of the optic chiasm [9]. In addition, planarians contain chemoreceptors and rheoreceptors at the anterior end which send projections to the cephalic ganglia [1]. Movement is permitted through the use of motile cilia on the ventral epithelium [9]. These organisms lack a coelom, and all space between the organs and nervous system is composed of mesenchyme [1]. The body wall contains a complex of longitudinal, diagonal, and circular muscle fibers which aid in negotiating obstacles [1]. Food is ingested through an extensible pharynx, which serves as both the mouth and anus, connected to a three-branch (triclad) digestive system [1].

Planarian Diversity and Distribution

Within the Tricladida exist three proposed taxonomic groups, which are based on their different habitats: Paludicola (freshwater planarians), Terricola (land planarians), and Maricola (marine planarians) [8]. These three taxonomic groups may be even further subdivided by classification of anatomical and external feature differences. "Molecular sequence data has helped to clarify the phylogenetic relationships and the evolutionary history of the Tricladida and in many cases facilitated a more natural classification. However, at certain levels resolution is still poor, thus requiring further studies" [8]. The genome of planarians is vast due to their ancient age and evolutionary processes making a difficult challenge to truly understand the depth of diversity between the proposed groups.

The distribution of planarians ranges from temperate to tropical and has been modified by introduction of species to newer continents. Climate and moisture play a large role in the distribution of these organisms as they are most vulnerable to desiccation. Terrestrial planarians are found scattered throughout temperate, tropical, and subtropical regions across the globe, whereas the majority of freshwater planarians are mainly confined to the temperate and tropical regions of North America, Europe, and Asia in which draught rarely occurs [8].

Parasitic Behavior and Treatment

Over a third of the world’s population is estimated to be infected with parasitic worms" [4]. Most cases of parasitic flatworm infections are associated with unsanitary drinking water, as these organisms are typically found near the bottom of freshwater sources. Symptoms of host infection result from egg deposition within the liver, gastrointestinal tract, or urinary bladder, resulting in granuloma formation and fibrosis [4]. Drugs such as Praziquantel (PZQ), an anthelmintic, can cure fluke infection by disrupting the neoblast regeneration pattern in planarians. Specifically, the drug causes increased levels of calcium which is suspected to be the main inhibitor of proper neoblast regeneration [5]. This disruption leads to regeneration of Planaria with two heads by inhibiting posterior expression, eventually driving them out of the host.

Stem Cells and Regeneration

Neoblasts represent approximately 25%-30% of all planarian cells [1]. Neoblast regeneration and differentiation is activated by the WNT signaling pathway, a signal transduction pathway which specifies the anterior and posterior axis in development. "Wnt signaling directly targets the nucleus, and it is broadly used to regulate cell fate, proliferation and self-renewal of stem and progenitor cells in any tissue and at any stage of metazoan life" [6]. Specifically, this pathway specifies posterior axis development, however, in the absence of the Wnt ligand, the protein beta-catenin is degraded inhibiting posterior specification and enhancing anterior expression markers. Without the Wnt pathway properly activated, a planarian will regenerate with two anterior halves due to lack of posterior expression regulated by beta-catenin. Studies have shown how RNAi, also known as RNA silencing, can inactivate the beta-catenin gene resulting in a lack of posterior expression markers and structures in regenerated planarians [3].

References

- Reddien, Peter W., and Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado. “Fundamentals of Planarian Regeneration.” Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, vol. 20, no. 1, Annual Reviews, Inc, 2004, pp. 725–57, doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114

- Rink, Jochen C., and Jochen C. Rink. “Stem Cell Systems and Regeneration in Planaria.” Development Genes and Evolution, vol. 223, no. 1, Springer-Verlag, 2013, pp. 67–84, doi:10.1007/s00427-012-0426-4.

- Kyle A. Gurley, et al. “β-Catenin Defines Head Versus Tail Identity During Planarian Regeneration and Homeostasis.” Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), vol. 319, no. 5861, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2008, pp. 323–27, doi:10.1126/science.1150029.

- Chan, John D., et al. “‘Death and Axes’: Unexpected Ca2+ Entry Phenologs Predict New Anti-Schistosomal Agents.” PLoS Pathogens, vol. 10, no. 2, Public Library of Science (PLoS), 2014, pp. e1003942–e1003942, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003942.

- Cioli, Donato, et al. “Schistosomiasis Control: Praziquantel Forever?” Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, vol. 195, no. 1, Elsevier B.V, 2014, pp. 23–29, doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.06.002.

- Almuedo-Castillo, Maria, et al. “Wnt Signaling in Planarians: New Answers to Old Questions.” The International Journal of Developmental Biology, vol. 56, no. 1-2-3, 2012, pp. 53–65, doi:10.1387/ijdb.113451ma.

- Alvarado, Alejandro Sánchez. “Planarians.” Current Biology, vol. 14, no. 18, Elsevier Inc, 2004, pp. R737–R738, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.005.

- Rink, Jochen C. Planarian Regeneration Methods and Protocols / Edited by Jochen C. Rink. 1st ed. 2018., Springer New York, 2018, doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-7802-1.

- Elliott, Sarah A., and Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado. “The History and Enduring Contributions of Planarians to the Study of Animal Regeneration.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Developmental Biology, vol. 2, no. 3, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2013, pp. 301–26, doi:10.1002/wdev.82.