Lichen

A lichen is a compound organism made up of two species. A fungus and a cyanobacteria or green algae live symbiotically, and both benefit from this mutualistic relationship. It was found that fungal or fungus-like parasites of cyanobacteria or unicellular algae gain fixed nitrogen from their ability to ensheath and/or invade specialized tissues of a host. This positively benefits the fungus, and allows the host a layer of protection in exchange for nutrients [10]. This protection is in the form of the overgrowth of the host that allows for the formation of an "inconspicuous microfilamentous, globose or crustose thalli which are usually referred to as microlichens." [9]. The most common types of cyanobacteria that contribute to lichen formation are Nostoc or Scytonema. The most common types of green algaes in lichen are pleurastrophycean green alga, such as Trebouxia, Pseudotrebouxia, or Myrmec. In exchange for a safe habitat to live in, the cyanobacteria or green algae provide food to the fungus from their photosynthetic processes [10].

Types of Lichen

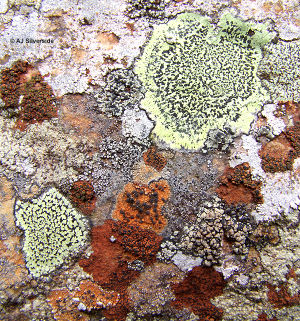

Of the 20,000+ known lichen types [8], they can occur in one of four main growth forms [5]:

- Crustose lichen are lichen that are pressed against their substrate. They form a crust over their substrate. (6) Their medulla is in direct contact with the substrate it is growing on [6].

- Squamulose lichen are lichen with a thallus, or a body that is not separated into stem and leaves, that is small, flat, and usually massed with overlapping scales, or squabbles [6].

- Foliose lichen are lichen with a thallus that generally form flat, leaf-like lobes with differentiated layers of tissue. The lower cortex is typically a different color and usually has rhizines to attach to it's substrate [6].

- Fruticose Lichen are lichen with a thallus that is extended up into a tufted or pendant branched structure [6]. They are free-standing branched tubes [5].

Biology

Unlike plants, lichen do not have a vascular system. This means they do not have a xylem or phloem to move nutrients and water around their plant body. Lichen get their water and nutrients by absorbing them from their surroundings [3]. The majority of the lichen's body is formed by filaments from the fungal body, and the varying density of these filaments defines the layers of the lichen [5].

Growth

Once the fungi ensheath or forms a layer over its host of cyanobacteria or algae, the formation of lichens can begin. Due to the mutualistic relationship, the green chlorophyll possessed by the host can be used for photosynthesis by lichens, something that otherwise would not be an option. In conjecture with this new photosynthesis, the lichens also gain nutrients from their host. In addition, lichens have a remarkable ability to absorb water from their surroundings through dew, fog, or even the air if the conditions are suitable for it. It is this remarkable ability that allows lichens to live in terribly harsh climatic regions [10].

Cortex

The outer layer of the lichen is called the cortex. The filaments in the cortex are thicker and more closely packed, providing a small amount of protection for the organism. [3] The densely packed filaments also helps to reduce the intensity of light, which can cause damage to the alga cells [5]. However, some lichens do not contain a cortex at all, and these are referred to as "byssoid lichens." [11]. These lichens instead have a thallus composed of hyphae and photobiont cells [11].

Symbiont Layer

Below the cortex, the fungal filaments are not so dense. This is the layer where the aglal cells are distributed [5]. This is the layer than photosynthesis occurs in.

Medulla

Fungal filaments, or medulla, make up most of the lichen organism. Hyphae are loosely packed in the middle of the lichen body, with thin cell walls and a threadlike structure [3]. This structure allows for generous air spaces and water-holding capabilities [12].

Rhizines

Some lichen use rhizines to attach to their substrate. Rhizines are fungal filaments extending out from the medulla. Rhizines do not move water or help the lichen breathe - their sole purpose is stabilizing the lichen down [3].

When rhizines are present in lichen, their location may vary. In some cases, they are found anywhere under the thallus, while in other cases they are still found under thallus, just in specific locations and not spread out. These differences in placement play an important role in how securely attached they are to their host [11].

The shape of the rhizines varies based on species, although in all species they perform the same function. Their structure can be anything from simple, linear bundles to highly branched conglomerates. From there, they may fork off or simply branched off of a main axis point, leaving some to be a mix between the two.

Holdfast

Some lichen use holdfasts to fasten themselves down. This is a central peg that extends out from the lichen thallus [3].

Ecology

Lichen play a huge role in the development of ecosystems, and also a huge role in established ecosystems. They play an important role in the water cycle in forests, greatly increasing the interception and absorption of precipitation [4]. Lichen are able to sequester limiting nutrients from the atmosphere, and these in turn become available to other organisms when lichen die, fall, and decompose, or through leachate [4]. The presence of lichen also provides increased habitat complexity for small organisms. There is a close relationship between lichen and invertebrates, including Arachnids such as orabitid mites, insects, rotifers, tardigrades, and spiders[4]. Providing habitat for these micro organisms is the base of the food chain, and provides food sources for the rest of the food web.

Pioneer Species

Lichen are considered pioneer species, or the first organism to appear in areas of primary succession [2] They are able to colonize bare rocks, and an ecosystem is then able to begin developing on them. The fungal partner in the lichen releases chemicals that break down rock minerals, which are then able to be consumed by the algal partner [9].

Indication

An indicator species is a species that tells something about the environment by their presence, or absence, in that environment. Lichens are indicators of environmental pollution. They have no way to detoxify and excrete harmful chemicals from the air, so absence of lichen in an ecosystem can be an indicator of environmental stress due to pollution [1].

References

[1] Trishala K. Parmar, D. R., and Y.K. Agrawal, 2016, Bioindicators: the natural indicator of environmental pollution: Frontiers in Life Science, v. 9, no. 2, p. 110-118.

[2] Science, D. E., 2010, Primary and Secondary Succession. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/fungi/lichens/lichenmm.html

[3] Lichen Biology, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/beauty/lichens/biology/index.shtml

[4] Ellis, Christopher J. “Lichen Epiphyte Diversity: A Species, Community and Trait-Based Review.” Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, vol. 14, no. 2, 2012, pp. 131–152., doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2011.10.001.

[5] Lichens: More on Morphology: Univeristy of California at Berkeley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/fungi/lichens/lichenmm.html

[6] Silverside, A. J., October 2012, Lichen thallus types, illustrated (Alan Silverside's photographs of lichens (FAQ)). http://www.lichens.lastdragon.org/faq/lichenthallustypes.html

[7] Microbiology, Lichens. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/microbiology/chapter/lichens/.

[8] Lichens: Systemtics: University of California at Berkeley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/fungi/lichens/lichensy.html

[9] Honegger, Rosmarie. “Tansley Review No. 60. Developmental Biology of Lichens.” The New Phytologist 125, no. 4 (1993): 659–77. Pg. 661.

[10] Biology, D. o., Lichens: Utah State University, p. What are they? How do the grow? https://herbarium.usu.edu/fun-with-fungi/lichens.

[11] Lepp, H., 2012, Form and structure - lichens, Australian National Botanic Gardens and Australian National Herbarium, Canberra. http://www.anbg.gov.au/lichen/form-structure.html

[12]Fungus - Form and function of lichens, Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/fungus.