Acorn ant

| |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Crematogastrini |

| Genus: | Temnothorax |

| Image Source: Bug Guide [1] | |

Acorn Ant Description

Acorn ants (Temnothorax genus) are a well-studied species found in both rural and urban areas of the eastern United States. The common name, "acorn ant," results from the fact that an entire colony (which typically contains between 50 and 200 worker ants, along with several queens) can live in hollowed-out nuts, such as acorns [2]. Acorn ants are amber to yellow in color, darkening with age, and they have 11-segmented antennae, along with a curved propodeal spine. The middle part of the ant's body (mesosoma) is covered in rough ridges (rugae) [3]. The Temnothorax genus has been notably studied for their social structures and behaviors, such as communication and responsibility within colonies [4].

Habitat & Range

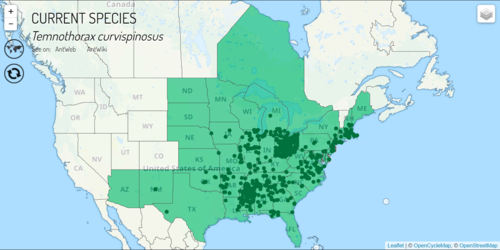

Starting along the eastern United States coast, acorn ants' range extends as far north as Maine, as far south as Florida, and as far west as Arizona. They can also be found in parts of Canada, including Ontario [5]. They are likely to occupy temperate and subtropical northern forests [3].

Nesting Habits

In addition to hollowed-out nuts, acorn ant nests can be found in hollow stems, insect galls, puffballs, and pinecones. Nests may also be under rocks or in soil, and they are usually found at lower elevations. Acorn ants are polydomous (they can inhabit several homes at the same time), which is useful in the event of a disturbance to a nest, as they can easily change where they reside [6]. In the summer, sub-colonies can build new nests near their main population's. During the winter, sub-colonies coalesce back into one large colony. But, during the winter, about half of the colony is lost, as ants either die off or migrate to start or join a colony [7].

Reproduction

Acorn ants are polygynous, meaning one colony can have multiple queens [3]. Male ants will reproduce with the queens in a colony, and larvae can be found inside a nest all year-round. After the eggs hatch into larvae, they will go through multiple molting stages. Eventually, larvae will metamorphose into a pupa and then grow into an adult ant. Female ants within a colony that are fed more when they are young grow to become queen ants. Queen and male ants have wings while worker ants (female) do not [8]. Eventually, multiple queens will work together to form a new colony (this process is called pleometrosis). Queens can also be adopted into an existing colony [9].

Diet

Acorn ants are generalist feeders, but most commonly eat liquid sugars from tree and plant leaves. These ants may also eat small insects for protein, like spring tails and dipterans (flies). Acorn ants may also partake in foraging, which is usually done in tandem. Foraging in tandem means that one ant will recruit another to follow and help them find and secure food. This recruited ant will recruit another to do the same, and the pattern continues. This strategy is particularly useful when there is a clumped food distribution. Foraging as a behavior for acorn ants is more common in the spring and summer [9].

Adaption to Rising Temperatures

The development of urban spaces has caused a rapid rise in environmental temperatures, especially with impermeable surfaces. Acorn ants have shown plasticity in their physiological response to these rising temperatures, and it was found that colonies present in these urban areas have better adapted to this temperature increase. This finding was correlated with both faster rates of diurnal temperature rise in urban acorn ant nest sites and more rapid spatial changes in temperature across urban foraging areas [2].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 “Species Temnothorax Curvispinosus.” BugGuide. https://bugguide.net/node/view/328106/tree.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diamond, Sarah E., Chick, Lacy D., Perez, Abe, Strickler, Stephanie A., Zhao, Crystal. (14 June 2018). "Evolution of plasticity in the city: urban acorn ants can better tolerate more rapid increases in environmental temperature." Conservation Physiology. 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/coy030.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Mackay, W. P.. (2000). "A review of the New World ants of the subgenus Myrafant, (genus Leptothorax) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Sociobiology. 36 (2): 265–434. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286112621_A_review_of_the_New_World_ants_of_the_subgenus_Myrafant_Genus_Leptothorax_Hymenoptera_Formicidae.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “Larger colonies do not have more specialized workers in the ant Temnothorax albipennis” Behavioral Ecology. (19 May 2009). 20 (5): 922-929. https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article-abstract/20/5/922/209417?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 “Temnothorax curvispinosus.” AntWiki, https://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Temnothorax_curvispinosus

- ↑ Healey, Christiane I. M., and Pratt, Stephen C.. (2008). “The Effect of Prior Experience on Nest Site Evaluation by the Ant Temnothorax Curvispinosus.” Animal Behaviour. 76 (3): 893–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.02.016.

- ↑ Pratt, Stephen C. (2005). "Behavioral mechanisms of collective nest-site choice by the ant Temnothorax curvispinosus." Insectes Sociaux. 52: 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-005-0823-z.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Holbrook, Tate. (17 Dec 2009). "Individual Life Cycle of Ants." ASU - Ask A Biologist. ASU - Ask A Biologist. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/individual-life-cycle

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pratt, Stephen C. (2008). “Efficiency and Regulation of Recruitment During Colony Emigration by the Ant Temnothorax Curvispinosus.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 62 (8): 1369–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0565-9.