Flavonoids

Flavonoids are a group of phytonutrients found in all plants on the planet. Functions of these chemicals in plants include UV protection, defense against invasive pathogens, pigmentation, and signaling in symbiosis. This group of chemicals can be broken down further into subgroups based on the makeup of their chemical structures. In foods, flavonoids are full of natural antioxidants and can be found in a multitude of food types.

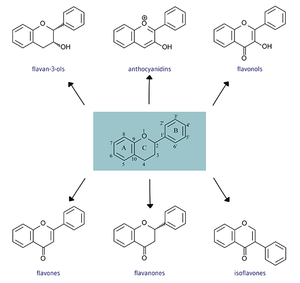

Chemical structures

All flavonoids consist of phenolic and pyrane rings and are generally insoluble. [2] Flavonoids differ in the arrangement of hydroxyl, methoxy, and glycosidic groups around a flavin backbone and from there form subgroups that include more specific chemicals. [1]

Flavones -Apigenin, Luteolin

Flavanones -Hesperetin, Naringenin, Eriodictyol

Flavonols -Quercetin, Kaempferol, Myricetin, Isorhamnetin

Flavan-3-ols -Catechins, Epicatechins, Epicatechin3-gallate, Epigallocatechin, Epigallocatechin 3-gallate, Gallocatechin, Theaflavin, Theaflavin 3-3’-digallate, Theaflavin 3’-gallate, Theaflavin 3-gallate, Thearubigins

Anthocyanidins -Cyanidin, Delphinidin, Malvidin, Pelargonidin, Peonidin, Petunidin

Role in plant growth

Within the Rhizosphere

Flavonoids aid in the interaction of plant roots with microorganisms in the surrounding area. [3] Roots can exude these chemicals through decomposing root caps and border cells. Once in the soil, flavonoids act as reducing agents and metal chelators towards metals. This increases the number of nutrients, particularly iron and phosphorous, available to the nearby plant roots.

Flavonoids are also key in the formation of nodules. Nodules are stores of fixed nitrogen created through a symbiotic relationship between plant roots and rhizobium bacteria. [6] Flavonoids improves transcription of nod genes by making access to RNA polymerase easier for the nodule to form. Conversely, nodule formation can be suppressed in order to maintain optimal conditions for the rate of nodule formation to remain unchanged.

Mycorrhizal fungi are also beneficiaries of flavonoids being present. Mycorrhizal fungi for hyphae in the soil which are then attracted to the exudates from the roots of a plant. The fungi then form ecto- or endomycorrhizal structures. Specifically, an isoflavonoid called coumestrol is heavily involved in the formation of hyphae. [3]

It is likely that flavonoids also play a role in the facilitation of arbuscular fungi invasions of the root. [3]

Flavonoid phytoalexins (antimicrobial and antioxidative substances) are activated in the case of an attempted breach of root tissue by an undesired outsider [3] These phytoalexins protect the root system from pathogens, undesirable bacteria, and even insects from interfering and harming their structures and/or growth space. These chemicals can be kept in dormant reserve for quick deployment if the need arises in the future. In terms of defense from pathogens, a flavonol called quercetin has been shown to repel attacks from E. coli by impeding ATPase activity (conversion of ATP to ADP resulting in a release of energy). [7]

Presence in foods

Flavonoids have been discovered to play a big role in the presence of antioxidants in common food sources. The five subgroups of flavonoids above exist as antioxidants within a multitude of common food items. [4]

Flavonols are found heavily in black tea and raw onions as well as in beer, coffee, and tomatoes. [4] Bee pollen has also found to contain flavonols. [5]

Dried and raw parsley contains more than 14,000 mg of flavones per gram of the plant. Flavones are also found in sweet, green, and hot chili peppers in addition to oranges and watermelons. [4]

Regular and decaffeinated black tea accounts for an overwhelming amount of flavan-3-ols consumed by humans, joined by peaches, pears, and bananas.

Flavanones are mainly found in oranges and grapefruit juice along with lemons and tangerines.

Anthocyanidins are commonly found in blueberries, strawberries, bananas, and cherries.

Medicinal applications

References

[1] Heim, Kelly E, et al. “Flavonoid antioxidants: chemistry, metabolism and structure-Activity relationships.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 13, no. 10, 1 May 2002, pp. 572–584., doi:10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00208-5.

[2] Kumar, Shashank, and Abhay K. Pandey. “Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview.” The Scientific World Journal, vol. 2013, 7 Oct. 2013, pp. 1–16., doi:10.1155/2013/162750.

[3] Hassan, S., and U. Mathesius. “The role of flavonoids in root-Rhizosphere signalling: opportunities and challenges for improving plant-Microbe interactions.” Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 63, no. 9, Feb. 2012, pp. 3429–3444., doi:10.1093/jxb/err430.

[4] Kyle, J.A.M. et al. Flavonoids, chemistry, biochemistry and applications. In Flavonoids in Foods. Anderson, O.M. et al., Ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fl. 2006

[5] Bhagwat, S., Haytowitz, D.B. Holden, J.M. (Ret.). 2014. USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata/flav

[6] Wang, Qi, et al. “Host-Secreted antimicrobial peptide enforces symbiotic selectivity in Medicago truncatula.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 26, Dec. 2017, pp. 6854–6859., doi:10.1073/pnas.1700715114.