Glomeromycota

The Glomeromycota are not as diverse as other phyla of fungi nor are there as many species. However they make up for this uniformity by being among the most abundant and widespread of all fungi. As far as we know, all species of Glomeromycota are mutualistic with plants, forming Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi.

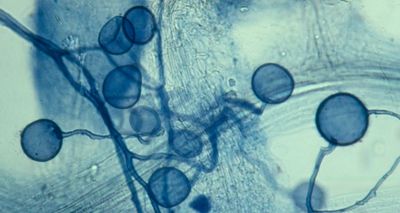

These fungi were considered to be members of the Zygomycota for many years, mainly because their hyphae lack septa and because their spores may superficially resemble zygospores. More recent genetic evidence shows that they are quite distinct from other fungi and definitely belong in a separate phylum. Palaeontologists have suspected this for a long time. The fossil roots of plants known to be as old as 450 million years clearly contain the hyphae and spores of Glomeromycota, showing this group to be among the oldest of fungi. The photograph above shows hyphae and spores of a species of Glomus, collected from the soil surrounding the roots of a balsam poplar tree. Such structures are indistinguishable from some fossil collections.

Reproduction

No member of the Glomeromycota has ever been grown in the laboratory independently of its plant associate. There is no evidence that the Glomeromycota reproduce sexually. Studies using molecular marker genes have detected little or no genetic recombination so it is assumed generally that the spores are formed asexually.

Colonization

AM fungi are obligate symbionts and none of these fungi has been cultivated without their plant hosts. Pure fungal biomass can be obtained only from cultures in transformed plant roots that can be cultivated in tissue culture, but only a small number of AM species are available in this form. Most samples can be contaminated by numerous other microorganisms, including fungi from other phyla, so progress with multigene phylogenies has been slow and the nuclear-encoded ribosomal RNA genes have remained the only widely accessible molecular markers.

Yet, in ecological terms, this is possibly the most important group of fungi because AM fungi form endomycorrhizal associations with about 80% of land plants. The association is essential for plant ecosystem function because the plants depend on it for their mineral nutrient uptake, which is efficiently performed by the mycelium of the fungal symbionts that extends outside the roots. Within root cells AM fungi form hyphal coils or the typical tree-like structures, the arbuscules.

Some also produce storage organs, termed vesicles (hence, another frequently used name for them – vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas or VAM-fungi). In phylogenetic terms they are important because they are the oldest unambiguous fungi known from the fossil record (see the Fossil Fungi section in Chapter 2). Put these two facts together and you get the suggestion that early colonisation of the land surface on Earth was promoted by the success of this plant-fungal symbiosis.