Glomeromycota

The Glomeromycota are limited in number compared to other phyla of fungi. However, they make up for this lack of diversity by being among the most proliferant and widespread of all fungi. As far as we know all species of Glomeromycota form mutualistic relationships with plants, in the role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi.

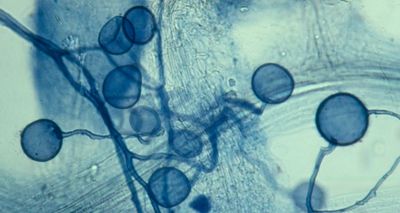

These fungi were considered to be members of the Zygomycota for many years, mainly because their hyphae lack septa and because their spores may superficially resemble zygospores. More recent genetic evidence shows that they are quite distinct from other fungi and definitely belong in a separate phylum. Paleontologists have suspected this for a long time. The fossil roots of plants known to be as old as 450 million years clearly contain the hyphae and spores of Glomeromycota, showing this group to be among the oldest of fungi. The right photograph shows hyphae and spores of a species of Glomus, collected from the soil surrounding the roots of a balsam poplar tree. Such structures are indistinguishable from those in the fossil record.

Phylogeny

Glomeromycota make up one of the seven different phyla of the true fungi kingdom. The six other phyla are named as Chytridiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Microsporidia, Ascomycota, and Basidiomycota. [4]

Reproduction

The Glomeromycota reproduction via sporeulation. There is no evidence that the Glomeromycota are able reproduce sexually. Studies using molecular marker in their genes have detected little to no evidence of genetic recombination, so it is assumed that the spores are formed asexually.

No member of the Glomeromycota has ever been grown in the laboratory independently of its plant associate.It is still not known exactly what these fungi need as nutrients.

Symbiotic Relationship

The Glomeromycota have symbiotic relationships with plants and evidence suggests that glomeromycota depend on the carbon and energy provided by their partner plants to survive.

Colonization

New colonization of arbuscular microrhysal fungi largely depends on the amount of inoculum present in the soil. Although pre-existing hyphae and infected root fragments have been shown to successfully colonize the roots of a host, germinating spores are considered to be the key players in new host establishment. Spores are commonly dispersed by fungal and plant burrowing herbivore partners, but some exhibiting air dispersal capabilities are also known to exist. Studies have shown that spore germination is specific to particular environmental conditions such as right amount of nutrients, temperature or host availability. It has also been observed that the rate of root system colonization is directly proportional to spore density in the soil.In addition, new data also suggests that arbuscular microrhysal fungi host plants also secrete chemical which factor in the attraction of the fungi and enhance the growth of developing spore hyphae towards the root system.

References

[1]"21st Century Guidebook to Fungi", David Moore, Geoffrey D. Robson and Anthony P. J. Trinci.

[2]"A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution". Mycol. Res.

[3]Zangaro, Waldemar, Leila Rostirola, Vergal Souza, Priscila Almeida Alves, Bochi Lescano, Ricardo Rondina, Luiz Nogueira, and Eduardo Carrenho. "Root Colonization and Spore Abundance of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Distinct Successional Stages from an Atlantic Rainforest Biome in Southern Brazil." Mycorrhiza 2013.

[4]Augusstyn, A. Managing Editor, Britannica, "Outline of Classification of Fungi"