Ciliates

Ciliates Overview

Ciliates are part of a group called protozoa, which means they are unicellular eukaryotic organisms. There are around 3,500 species that have been described by scientists with the potential of thousands more to still be discovered. Ciliate species can have a wide range in not only size, but complexity. These species can measure anywhere from 10 µm to as large as 4 mm long and include some of the most morphologically advanced protozoans

Ciliates are easily recognized by their cilia, hair-like organelles which are structurally similar to flagella. These organelles can be found in most members of the group. Cilia are more numerous and generally shorter than flagella. and are variously used in swimming, eating, staying in place, and other general movement.

Ciliates are protists and love water. These organisms can be found almost anywhere there is water. Besides soil, Ciliates can be found in lakes, ponds, rivers, and even oceans.

Some Examples of Ciliates:

Paramecium : First ciliate to be used extensively for genetic studies, because conjugation could be controlled. Normally feeds on bacteria.

Tetrahymena : Used in genetics because of methods for controlling conjugation so that it occurs synchronously in a large populations. Relatively easy to isolate the two kinds of nuclei.

Stentor : Large ciliate used for grafting and micromanipulations. Its morphology of its outer layer is revealed by bands of blue pigment.

History

The oldest ciliate fossils known are from the Ordovician Period. A separate description of fossil ciliates was published in 2007, of which came from the Doushantuo Formation in the Ediacaran Period.

Cell Structure

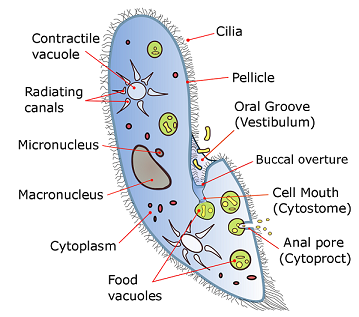

Nuclei

Ciliates have a set of two different of nuclei, which is different from most protists. The first is called the diploid micronucleus, which is the smaller of the two. This nucleus carries the germline of the cell and is used to pass genetic material to offspring, meaning it is specialized for sexual exchange. As such, this nucleus does not contain nucleoli, meaning the micronucleus does not share its genes. The second, larger, nucleus is called the polyploid macronucleus, which takes care of general cell regulation. This macronucleus is formed by the micronucleus and displays the phenotype of the organism. The macronucleus is the one that allows vegetative growth because it is specialized with nucleoli to move RNA into ribosomes.

Conjunction

This is what happens when the macronucleus needs to be regenerated due to cell age. The process involves two cells lining up and the micronuclei undergoing meiosis and then fuse to form new micronuclei and macronuclei.

Cell Body

Ciliates also contain several vacuoles that enclose food and waste. Digestive vacuoles form in the gullet as food particles are ingested, and then are circulated through the cell. Any remaining waste in these vacuoles is discharged through a point in the cell membrane called the cytoproct. Ciliates also have contractile vacuoles, which collect water and expel it from the cell to maintain osmotic pressure.

Reproduction

Ciliates reproduce asexually. This process involves various cases of fusion, incliuding binary. During fission, the micronucleus undergoes mitosis and the macronucleus undergoes amitosis. Afterwards, the cell divides in two, each with a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.

The other types of fission that can occur in ciliate groups include:

Budding: the emergence of small offspring from the body of a mature parent Strobilation: multiple divisions along the cell body, producing a chain of new organisms Palintomy: multiple fissions, usually within a cyst

Feeding

Ciliates are mostly heterotrophic, meaning they feed on smaller organisms. Food such as bacteria and algae, are swept into the”mouth” by the organism’s cilia. The food is moved by the cilia through the mouth pore into the gullet, which forms food vacuoles. Feeding techniques vary from species to species. Some ciliates are mouthless and feed by osmotrophy, while others are predatory and feed on other protozoa. There are also ciliates that parasitize animals.

References

[1] Beaver, John, and Thomas Crisman. “Microbial Ecology.” Microbial Ecology, 2nd ed., vol. 17, Springer-Verlag, 1989, pp. 111–136. SpringerLink.

[2] Berthold, A., and M. Palzenberger. “Biology and Fertility of Soils.” Biology and Fertility of Soils, 4th ed., vol. 19, Springer-Verlag, 1995, pp. 348–356. SpringerLink.

[3] “Ciliates.” Ciliates, California Institute of Technology.

[4] Ekelund, Flemming, and Reginn Ronn. “Notes on Protozoa in Agricultural Soil with Emphasis on Heterotrophic Flagellates and Naked Amoebae and Their Ecology.” FEMS Microbiology Reviews, vol. 15, no. 4, Dec. 1994, pp. 321–353. Wiley Online Library.

[5] Foissner, Wilhelm & Berger, Helmut. (1996). A user-friendly guide to the ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) commonly used by hydrobiologists as bioindicators in rivers, lakes, and waste waters, with notes on their ecology. Freshwater Biology. 35.

[6] Foissner, Wilhelm & O'Donoghue, PJ. (1989). Morphology and infraciliature of some freshwater ciliates (Protozoa : Ciliophora) from Western and South Australia. Invertebrate Systematics - INVERTEBR SYST. 3. 10.

[7] Li, C.-W.; et al. (2007). "Ciliated protozoans from the Precambrian Doushantuo Formation, Wengan, South China". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 286: 151–156.

[8] Waggoner, Ben. “Ciliata: Morphology.” More on Morphology of the Ciliata, University of California Museum of Paleontology, 2 Dec. 1995.