Black Willow

Overview

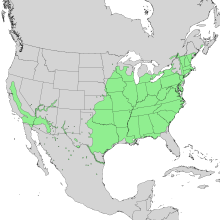

Salix nigra is a deciduous tree species that excels in areas of high moisture content such as swamps, river banks and drainage ditches, or almost anywhere that contains adequate lighting and water. These locations usually occur in areas that are near or just below the water level. It is a fast growing yet short lived tree that has an extensive range through Eastern North America as well as parts of California and the Southwest. Black willow trees are a dioecious species which means the males and females are indistinguishable from one another with the only exceptions being during flowering season and during the seed developmental process. The beginning of the flowering season begins in February in the southern range and goes through the end of June in the north. The flowers do contain nectar meaning that the majority of the pollination process is done by insects. That being said, the pollen can still be carried by the wind as well. The seeds of Salix nigra are small, light brown, and have a capsule shape, and begin to break open and release seedlings that are coated in little hairs.

Ecological Significance

"Various vertebrate animals also rely on Black Willow as a food source or as a provider of protective habitat. Both the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) and Wood Turtle (Clemmys insculpta) feed on fallen willow leaves and/or catkins (Lagler, 1943). The Ruffed Grouse, White-throated Sparrow, and such ducks as the Mallard and Northern Pintail feed on willow buds and/or catkins during the spring, when other food sources are scarce (Bennetts, 1900; Devore et al., 2004). Some birds, including the Rusty Grackle, Yellow Warbler, and Warbling Vireo, occasionally use willows as the location for their nests. Black Willow is one of the trees that the Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker drills holes into so that it can feed on the sap. Deer, elk, and cattle are known to browse occasionally on the leaves and twigs of this tree, while beavers feed on the wood and use the branches in the construction of their dams and lodges (Martin et al., 1951/1961)."

Cultural Uses

It is also the very useful for treating minor aches and pains because it has salicin which is the basic ingredient of aspirin but now the salicylic acid is synthesized instead of being taken from the trees themselves. It is the most commercially used species of willow because of its strength, and shock resistance and also the fact that it doesn’t splinter with ease. It’s mostly used for boxes and crates as well as wood turning and table tops, wooden carvings etc.

Soil Restoration Techniques

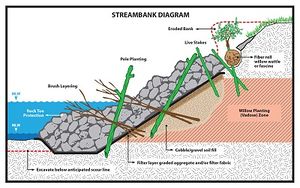

In addition to all of the uses for this species, we are now studying the ways in which willow has the ability to take heavy metals out of the soil. It is starting to be used in remediation and the endophytes that are living within the trees tissues are showing to have the capacity to enhance the trees growth and resistance to biotic and abiotic stressors by things such as nitrogen fixation and the production of phytohormones. Mercury and selenium can also be converted by plants into a volatile form to release and dilute into the atmosphere. Black willows are very effective when it comes to soil stabilization, so many projects that require erosion control such as river restoration will often use this species in their efforts. “Heavy metals cannot be metabolized, therefore the only possible strategy to apply is their extraction from contaminated soil and transfer to the smaller volume of harvestable plants for their disposal biomass can also be used in producing energy and, if economically profitable, metals can be eventually recovered”

References

1. https://www.ernstseed.com/products/bioengineering-materials/

2. http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/bl_willow.htm

3. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Society of American Foresters, Washington, DC. 148 p.

4. Johnson, R. L., and J. S. McKnight. 1969. Benefits from thinning black willow. USDA Forest Service, Research Note SO-89. Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA. 6 p. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native and naturalized). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 541. Washington, DC. 375 p.

5. McKnight, J. S. 1965. Black willow (Salix nigra Marsh.). In Silvics of forest trees of the United States. p. 650-652. H. A. Fowells, comp. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 271. Washington, DC.

6. McLeod, K. W., and J. K. McPherson. 1972. Factors limiting the distribution of Salix nigra. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 100(2):102-110.

7. Randall, W. K. 1971. Willow clones differ in susceptibility to cottonwood leaf beetle. In Proceedings, Eleventh Southern Forest Tree Improvement Conference. Southern Forest Tree Improvement Committee Sponsored Publication 33. p. 108-111. Eastern Tree Seed Laboratory, Macon, GA.

8. Sakai, A., and C. J. Wiser. 1973. Freezing resistance of trees in North America with reference to tree regions. Ecology 54(l):118-126.

9. Taylor, F. W. 1975. Wood property differences between two stands of sycamore and black willow. Wood and Fiber 7(3):187-191.

10. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs and woody vines of the Southwest. University of Texas Press Austin 1104 p.

11. Article homeguides.sfgate.com/willow-tree-fungus