Basidiomycota

Basidiomycota

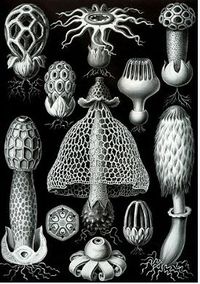

Basidiomycota is a monophyletic group of fungi encompassing more than 31,000 species. The Basidiomycota are also referred to as "Basidiomycetes" or "club fungi". Basidiomycota and Ascomycota together make up the sub-kingdom Dikarya which means higher fungi. The defining feature of Basidiomycota is their club-shaped structure known as the basidium which is where basidiospores are produced [7]. The Basidiomycota are of great ecological importance particularly in forest ecosystems due to their ability to decompose and recycle nutrients, especially lignin [7]. Additionally, Basidiomycota are a food source for many insects due to their rich carbohydrate and protein content. To plants, many basidiomycetes have been found to be parasitic and agents of disease [5]. Despite many basidiomycetes forming parasitic relationships with plants some form mutualistic relationships, most notably, ectomycorrizae [4]. Other mutualistic symbioses include lichens, liverworts, and fungus farming by ants and termites. Some of the most well-known basidiomycetes include mushrooms, toadstools, rusts, and smuts.

Characteristics

Basidiomycota vary greatly in morphological features depending on the species. Basidiomycota can be unicellular or multicellular, sexual or asexual, terrestrial or aquatic. However, something most basidomycota share is the production of basidia or the cells on which sexual spores are produced [8]. Basidiomycota are also all dikaryons, meaning that each cell in the thallus contains two haploid nuclei [6]. Another distinguishing feature of Basidiomycota are their clamp connections or hyphal outgrwoths that form from the division of cells in dikaryotic hyphae. In this process, one nuclei divide in the main axis of hypha, while the other divides into the clamp.

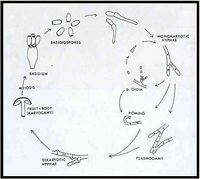

Life Cycle

Basidiomycota have a distinguished life cycle from other fungi. Basidiospores typically have a single haploid nucleus. When basidiospores germinate they produce hyphae with a single nucleus, known as a monokaryon. During growth, two monokaryons of different mating types will fuse either by hyphal fusion or with a small spore known as an oidium. The process of fusion in Basidiomycota is known as plasmogamy. Finally, the nuclei divide and the daughter nuclei pair has two nuclei, one of each mating type. It is at this point that a fungus is referred to as a dikaryon. Basidiomycota will grow as a dikaryon until an environmental cue causes them to produce fruitbodies. It is then that the two haploid nuclei fuse, known as karyogamy, and form a diploid nucleus. After meiosis there are four haploid nuclei which migrate into the basidiospores where the life cycle begins again [3]. The basidiospores reside at the tip of a horn known as a sterigma and they are forced out, known as ballistospore discharge, upon maturity.

Ballistospore being ejected: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GZLM1ouhW1Y

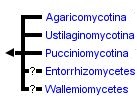

Taxonomy

Basidiomycota are recognized as a monophyletic phylum comprised of five classes. These classes include Agaricomycotina, Ustilaginomycotina, Pucciniomycotina, Entorrhizomycetes, Wallemiomycetes. Agaricomycotina consists of jelly fungi, yeasts and mushrooms while Ustilaginomycotina consist of smut fungi, and Puccinomycotina include rusts, yeasts, smut-like and jelly-like fungi. The phylogenetic position of both Entorrhizomycetes and Wallemiomycetes are still being debated [2].

Uses

Basidiomycota greatly effect ecosystem functioning primarily through being detritivores and provideing ecosystem services. Basidiomycota absorb nutrients by feeding on decaying matter and thus, play a significant role in the carbon cycle and nutrient cycle [6]. A popular trailmark of Basidiomycota are their ability to form fairy rings. Fairy rings are a cicrle of Basidiomycota arranged around dead leaves and roots in grasslands. In many folklore stories, these fairy rings have been present, greatly influencing art and literature. The rings expand every year and release nitrogen to the soil which produces very lush grass. In addition to ecosystem servicing, Basidiomycota are eaten both through cultivation and in the wild as mushrooms. Some Basidiomycota produce deadly toxins, one familiar to humans is phalloidin, used for fluorescent stains for viewing cytoskeletons in many biology labs [1]. Furthermore, Basidiomycota members of the genus Psilocybe are known to cause hallucinogenic effects and have been traditionally used in many Central American indigenous cultures [6].

References

[1] Benjamin, D.R. 1995. Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York.

[2] Brondz, I. (2014). Fungi: Classification of the Basidiomycota. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology: Second Edition (pp. 20–29). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384730-0.00139-7

[3] Deacon, J. (n.d.). Basidiomycota. Retrieved May 7, 2018, from http://archive.bio.ed.ac.uk/jdeacon/microbes/basidio.htm

[4] Hood, I. a. (2006). The mycology of the Basidiomycetes. Heart Rot and Root Rot in Tropical Acacia Plantations. Workshop in Yogyakarta Indonesia Feb. 2006. ACIAR Proceedings No. 124 Canberra., (124), 7–9.

[5] Kirk, P. M., Cannon, P. F., Minter, D. W., & Staplers, J. A. (2008). Basidiomycota. In Dictionary of the Fungi (pp. 78–82).

[6] Swann, Eric and David S. Hibbett. 2007. Basidiomycota. The Club Fungi. Version 20 April 2007.http://tolweb.org/Basidiomycota/20520/2007.04.20 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

[7] Taylor, T. N., Krings, M., Taylor, E. L., Taylor, T. N., Krings, M., & Taylor, E. L. (2015). 9 – Basidiomycota. In Fossil Fungi (pp. 173–199). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387731-4.00009-8

[8] Stolze-Rybczynski, J. L., Cui, Y., Stevens, M. H. H., Davis, D. J., Fischer, M. W. F., & Money, N. P. (2009). Adaptation of the spore discharge mechanism in the Basidiomycota. PLoS ONE, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004163