Rotifers

Rotifers Overview

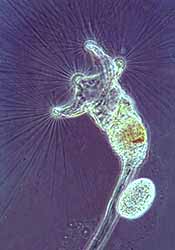

Rotifers are microscopic organisms that make up the phylum of Rotifera. Rotifers are found in a variety of water environments. This includes moisture in the soil, where the organisms survive within the thin films of water that are formed around particles of soil. Other locations rotifers can be found include pond/lake bottoms or other still water locations as well as leaf litter, dead trees, and lichens/mosses.

First described in 1696, most rotifers are around 0.1–0.5 mm long, however their size isn’t limited to that range. Rotifers have many different forms, their body shapes ranging from spherical, to wide and flattened, or long and thin.

About 2200 species of rotifers have been described. Their taxonomy is split into three classes:

Monogononta is the largest with over 1500 species

Bdelloidea has around 350 species

The “primitive” Seisonidea has just 2 species.

Rotifers are not commonly favored for fossilization because of their small size and soft bodies. Their only hard parts, their jaws, may be preserved for fossil records, but their microscopic size makes detection very difficult.

Anatomy and Body Structure

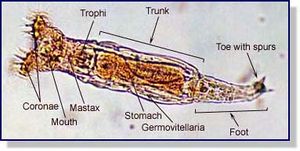

A rotifer’s body can be divided into three regions: trunk, head, and foot. In some rotifera the foot may be absent, depending on whether the species is sedentary or free swimming.

Head

In most species, the head carries a crown shaped organ, a ciliated structure called the Corona. Rotifers use this structure to create a vortex that funnels water into the organism’s mouth. The rotifer sifts through the stream, catching and grinding up its food with its trophi, which act as jaws. The trophi are characteristic of rotifers and nearly all species have them.

Trunk

The trunk of this organism encloses most of its internal organs, including the stomach and reproductive organs. It is the largest portion and forms most of the body of the rotifer. The trunk is segmented externally, making it appear segmented internally, when really the internal structure is uniform.

Foot

The foot ends in a series of "toes" containing a cement gland to attach the animal to nearby objects or substratum. Most species can retract the foot partially or entirely into the trunk, however in many free-swimming species, the foot may be very small or even absent.

Reproduction

Reproduction in rotifers is a bit strange. There are several forms of reproduction observed in rotifers. Some species use a form called parthenogenesis. In these cases, the species can develop asexually from an unfertilized egg. In other cases, species reproduce sexually, with the males usually only surviving long enough to produce sperm to fertilize eggs. The fertilized eggs then form resistant zygotes that can survive if the local water supply should dry up. The eggs are released into the water where they hatch. There is no particular breeding season with these animals. Up to 7 eggs can be released at one time and will hatch within 12 hours. Upon hatching, rotifers need about 18 hours to reach sexual maturity.

Feeding

Rotifers’ diet must consist of matter small enough for their tiny mouths during filter feeding because they are microscopic. While primarily omnivorous, some species have been known to be cannibalistic. The diet of rotifers includes particles up to 10 micrometres in size, which most commonly consists of organic detritus and dead bacteria, algae, and protozoans. They also contribute to nutrient recycling. Rotifers are in turn prey to carnivorous secondary consumers, including shrimp and crabs.

References

“Annotated Checklist of the Rotifers (Phylum Rotifera), with Notes on Nomenclature, Taxonomy and Distribution.” Zootaxa, by Hendrik Segers, vol. 1564, Magnolia Press, 2007, pp. 1–104.

[2] Baqai , Aisha, et al. “Rotifers : the ‘Wheel Animalcules.’” Introduction to the Rotifera, University Of California at Berkeley, 1 May 2000..

“Environmental and Endogenous Control of Sexuality in a Rotifer Life Cycle: Developmental and Population Biology.” Evolution And Development, by John J Gilbert, 1st ed., vol. 5, pp. 19–24.

“Epizoic and Parasitic Rotifers.” Hydrobiologia, by L. May, vol. 186, 1989, pp. 59–67. SpringerLink.

Gilbert, John J. “Rotifer Ecology and Embryological Induction.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 11 Mar. 1966.

Herzig A. (1987) The analysis of planktonic rotifer populations: A plea for long-term investigations. In: May L., Wallace R., Herzig A. (eds) Rotifer Symposium IV. Developments in Hydrobiology, vol 42. Springer, Dordrecht.

[3] “Rotifers. A General Introduction.” Micrographia, 1978, www.micrographia.com/specbiol/rotife/homebdel/bdel0100.htm

[1] Webster, Thomas, et al. “Bdelloid Rotifers: Female Filter Feeders.” Www.amateurmicroscopy.net...Bdelloid Rotifers, 2003, www.photomacrography.net/amateurmicroscopy/Articles/Rotifers/rotifers.htm.

Wright, Jeremy. “Rotifera (Wheel or Whirling Animals).” Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 2014.