Diazotrophs: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

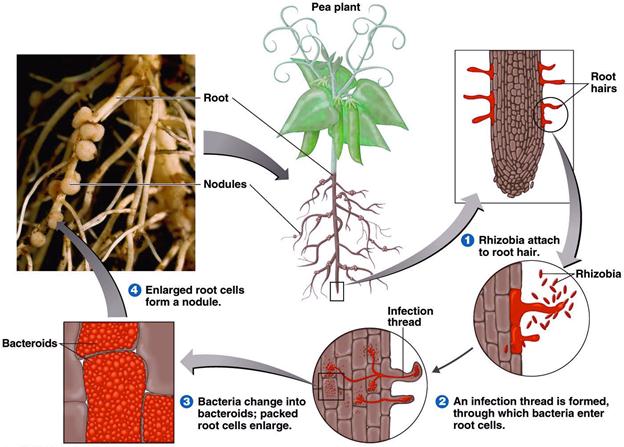

Bacteria from the genus ''Rhizobium'' form a relationship with leguminous plants. Parasponia is the only non-legume genus that can form a symbiotic relationship with these bacteria. They do this by the nodulation, or nod, factor - a signal of amino acids that alert the plant. When the bacteria sends out this signal, the plant responds with root hairs curling around the bacteria. As the intracellular infection threads from the bacteria begin to grow into the plants, the plant begins nodule formation. The nodule become surrounded by a membrane from plant material. Symbiosome is the name for this compartmentalization of bacteria within the plant, and it is the symbiosome that acts as the pathway between the plant and the bacteria, allowing for nutrient exchange. | Bacteria from the genus ''Rhizobium'' form a relationship with leguminous plants. Parasponia is the only non-legume genus that can form a symbiotic relationship with these bacteria. They do this by the nodulation, or nod, factor - a signal of amino acids that alert the plant. When the bacteria sends out this signal, the plant responds with root hairs curling around the bacteria. As the intracellular infection threads from the bacteria begin to grow into the plants, the plant begins nodule formation. The nodule become surrounded by a membrane from plant material. Symbiosome is the name for this compartmentalization of bacteria within the plant, and it is the symbiosome that acts as the pathway between the plant and the bacteria, allowing for nutrient exchange. | ||

[[File:lec18_clip_image006.jpg| | [[File:lec18_clip_image006.jpg|frame|The process of nodule formation happening between a bacteria and plant, resulting in a symbiotic relationship. The bacteria fixes nitrogen that will become available to the plant, and the plant provides shelter, carbon, and energy to the bacteria.]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 18:47, 8 March 2018

Diazotrophs are a group of prokaryotic organisms with the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into ammonium or ammonia, forms usable to plants. There are two types of terrestrial diazotrophs: those free living in the soil, and those that form symbiotic relationships with plants.

Nitrogen makes up the majority of the Earth’s atmosphere, but is mostly found in a form unusable to organisms. Atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is found as two nitrogen atoms held together by a triple bond. In this form, nitrogen is inaccessible. Diazotrophs have the ability to split, or “fix” these bonds, freeing the nitrogen molecules.

Free Living Diazotrophs

Symbiotic Diazotrophs

The enzymes that are needed to fix nitrogen are easily damaged by oxygen, so some diazotophs form symbiotic relationships with plants. In this relationship, diazaotophs are protection from oxygen's damaging properties, while also being supplied carbon, and energy. In exchange for this, plants are able to benefit from the nitrogen.

The Rhizosphere

Nod Factor

Bacteria from the genus Rhizobium form a relationship with leguminous plants. Parasponia is the only non-legume genus that can form a symbiotic relationship with these bacteria. They do this by the nodulation, or nod, factor - a signal of amino acids that alert the plant. When the bacteria sends out this signal, the plant responds with root hairs curling around the bacteria. As the intracellular infection threads from the bacteria begin to grow into the plants, the plant begins nodule formation. The nodule become surrounded by a membrane from plant material. Symbiosome is the name for this compartmentalization of bacteria within the plant, and it is the symbiosome that acts as the pathway between the plant and the bacteria, allowing for nutrient exchange.

References

[1] Streng, Arend, et al. “Evolutionary Origin of Rhizobium Nod Factor Signaling.” Plant Signaling & Behavior, vol. 6, no. 10, 2011, pp. 1510–1514., doi:10.4161/psb.6.10.17444.

[2] Stein, Lisa Y, and Martin G Klotz. “The Nitrogen Cycle.” Current Biology Magazine , vol. 26, no. 3, 8 Feb. 2016, pp. R94–R98.

[3] Jetten, Mike S. M. “The microbial nitrogen cycle.” Environmental Microbiology, vol. 10, no. 11, 2008, pp. 2903–2909., doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01786.x.

[4] Norman, Jeffrey S, and Maren L Friesen. “Complex N acquisition by soil diazotrophs: how the ability to release exoenzymes affects N fixation by terrestrial free-Living diazotrophs.” The ISME Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, 1 Feb. 2017, pp. 315–326., doi:10.1038/ismej.2016.127.

[5] Burgmann, Helmut, et al. “Effects of model root exudates on structure and activity of a soil diazotroph community.” Environmental Microbiology, vol. 7, no. 11, 1 Nov. 2005, pp. 1711–1724., doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00818.x.

[6] Burgmann, H., et al. “New Molecular Screening Tools for Analysis of Free-Living Diazotrophs in Soil.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 70, no. 1, Jan. 2004, pp. 240–247., doi:10.1128/aem.70.1.240-247.2004.

[7] Poulin, Jessica. Evolutionary Biology Lab Manual. 8th ed.