Myriapoda: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Anatomy and Body Structure== | == Anatomy and Body Structure== | ||

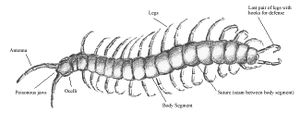

[[File:MyriaAnat.jpg|thumb|right|Example of Myriapoda anatomy. Notice segements and appendages. The relationship between these body parts varies between classes and species [6]]] | |||

Because Myriapoda are part of the group Arthopoda, this means they are [[invertebrates]] with segmented bodies. Pairs of appendages are connected to these segments and are used for movement, sensory, hunting, etc. They also have a single pair of antennae, with many species having eyes.The mouth lies on the underside of the head, with a pair of mandibles inside. The heart in myriapods is a long tubular organ that extends through the body instead of having blood vessels [2]. | Because Myriapoda are part of the group Arthopoda, this means they are [[invertebrates]] with segmented bodies. Pairs of appendages are connected to these segments and are used for movement, sensory, hunting, etc. They also have a single pair of antennae, with many species having eyes.The mouth lies on the underside of the head, with a pair of mandibles inside. The heart in myriapods is a long tubular organ that extends through the body instead of having blood vessels [2]. | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

[1]Waggoner, Ben. “Introduction to the Myriapoda.” University Of California Museum of Paleontology, University Of California at Berkeley, 21 Feb. 1996, www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/arthropoda/uniramia/myriapoda.html. | [1]Waggoner, Ben. “Introduction to the Myriapoda.” University Of California Museum of Paleontology, University Of California at Berkeley, 21 Feb. 1996, www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/arthropoda/uniramia/myriapoda.html. | ||

[ | [2]“The Geological Record and Phylogeny of the Myriapoda.” Arthropod Structure & Development, by David A. Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, 2nd-3rd ed., vol. 39, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 174–190. | ||

[3]“Anthropoda - Myriapoda.” Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates. Accessory Sex Glands, by K. G. Adiyodi et al., vol. 3, John Wiley & Sons, 1988, pp. 473–476. | |||

“The Geological Record and Phylogeny of the Myriapoda.” Arthropod Structure & Development, by David A. Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, 2nd-3rd ed., vol. 39, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 174–190. | “The Geological Record and Phylogeny of the Myriapoda.” Arthropod Structure & Development, by David A. Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, 2nd-3rd ed., vol. 39, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 174–190. | ||

[5]“8 Earth History.” An Introduction to Geology, Salt Lake Community College, opengeology.org/textbook/8-earth-history/. | [5]“8 Earth History.” An Introduction to Geology, Salt Lake Community College, opengeology.org/textbook/8-earth-history/. | ||

| Line 72: | Line 70: | ||

[3] “Garden Symphylans.” Symphylan Identification, Oregon State University, mint.ippc.orst.edu/symphid.htm. | |||

Miyazawa, Hideyuki, et al. “Molecular Phylogeny of Myriapoda Provides Insights into Evolutionary Patterns of the Mode in Post-Embryonic Development.” Scientific Reports, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, doi:10.1038/srep04127. | |||

[5] Tree of Life Web Project. 2002. Pauropoda. pauropods. Version 01 January 2002 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Pauropoda/2531/2002.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/ | |||

[1]Haulter, Josh. “How Do I Create a BioActive Vivarium?” TheBioDude, 2 Jan. 2017, www.thebiodude.com/blogs/how-do-i-create-a-bioactive-vivarium. | |||

Revision as of 22:52, 7 May 2019

Myriapoda Overview

Myriapoda is a subphylum of Arthropoda and contains over 13,000 species, almost all of which are terrestrial. Species include various millipedes and centipedes, among others. The group is named “Myriapod” after one of their most distinguishable features, their myriad of legs. While this suggests their number of legs is countless, in reality myriapods range anywhere from having nearly 200 pairs of appendages to fewer than ten. The size of these organisms can vary as well; some species are microscopic while others can reach lengths of over 30 cm [1].

Anatomy and Body Structure

Because Myriapoda are part of the group Arthopoda, this means they are invertebrates with segmented bodies. Pairs of appendages are connected to these segments and are used for movement, sensory, hunting, etc. They also have a single pair of antennae, with many species having eyes.The mouth lies on the underside of the head, with a pair of mandibles inside. The heart in myriapods is a long tubular organ that extends through the body instead of having blood vessels [2].

Reproduction

In order to reproduce, the male myriapod produces a spermatophore, or sperm capsule which is transferred to the female externally. The female uses this capsule to lay its eggs. When they hatch, the larvae appear as smaller versions of the adults, with only a few segments and few pairs of legs. Additional segments and leg pairs develop as the organism moults and grows [3].

Classification

There are four groups of Myriapoda. Each of these groups is believed to be monophyletic, meaning they descended from a common ancestor, however the specific relationships between them are less certain and not yet completely understood [1].

Chilopoda

This class includes true centipedes like the one shown. These organisms have only one pair of legs per body segment, including a modified pair of claws or mandibles at the front of the insect. Centipedes can have a varying number of legs, ranging from 30 to 354, although they will always have an odd number of pairs of legs. Some species are equipped with poison glands, which are used to hunt/capture prey, meaning centipedes are carnivorous. There are an estimated 8,000 species of centipede while only 3,000 have been described [4].

Diplopoda

This class is dominated by myriapods called Millipedes. The segments that make up the bodies of these organisms were formed by the fusion of two adjacent embryonic segments; meaning, each segment of a millipede bears two pairs of legs. This explains the name Diplopoda which means “double legs”. There are 16 orders and around 140 families classified off this class, making Diplopoda the largest of the myriapoda classes. Millipedes are unlike centipedes in that they are very slow moving and are detrivores, meaning they feed on decaying litter and vegetation. However, some eat fungi and a very small minority are predatory [5].

Symphyla

This class consists of very small, soil-dwelling, myriapods that resemble translucent centipedes (although are more closely related to millipedes). Juveniles have six pairs of legs, but as they grow, eventually develop twelve pairs of legs. These organisms use their long antennae as sense organs because they lack eyes. They are typically found in soil from the surface down to a depth of about 50 cm. They move through the pores between soil particles and consume decaying vegetation. Despite this, Symphyla are considered pests and can do considerable harm to agriculture [6].

Pauropoda

This class is often referred to as pseudocentipedes because of how similar in appearance they are to their relatives. However, the similarities mostly stop there. These organisms are very small and pale and feed on mold and different forms of fungi [7].

History

There are Cambrian fossils that exist which resemble myriapods, however the oldest unequivocal myriapod fossil is of a millipede from around 428 million years ago (Silurian Period)[8].

An ancient class of Myriapoda, Arthropleuridea are now extinct. Dying out in the Permian, some members of this class are most famously known as giant millipedes. These arthropods were some of the largest to ever live, were probably herbivorous, and were thought to reach sizes of 3 metres long [8].

References

[1]Waggoner, Ben. “Introduction to the Myriapoda.” University Of California Museum of Paleontology, University Of California at Berkeley, 21 Feb. 1996, www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/arthropoda/uniramia/myriapoda.html.

[2]“The Geological Record and Phylogeny of the Myriapoda.” Arthropod Structure & Development, by David A. Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, 2nd-3rd ed., vol. 39, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 174–190.

[3]“Anthropoda - Myriapoda.” Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates. Accessory Sex Glands, by K. G. Adiyodi et al., vol. 3, John Wiley & Sons, 1988, pp. 473–476.

“The Geological Record and Phylogeny of the Myriapoda.” Arthropod Structure & Development, by David A. Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, 2nd-3rd ed., vol. 39, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 174–190.

[5]“8 Earth History.” An Introduction to Geology, Salt Lake Community College, opengeology.org/textbook/8-earth-history/.

[6] “Centipede Anatomy | Diagrams and Facts About Centipedes.” Animal Corner, 29 Apr. 2008, animalcorner.co.uk/centipede-anatomy/.

[7] Cleverly, Jonathan. “Meet the African Giant Millipedes .” Jonathan's Jungle Roadshow, www.jonathansjungleroadshow.co.uk/meet-the-african-giant-millipedes.html.

Edgecombe, Gregory D., and Gonzalo Giribet. “Evolutionary Biology of Centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda).” Annual Review of Entomology, vol. 52, no. 1, 2007, pp. 151–170., doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091326.

[2] “Facts about Centipede: Appearance, Habitat, Symptoms, and Treatments.” Insect Pest Facts, 10 Jan. 2018, www.insectpestfacts.com/centipede/.

[3] “Garden Symphylans.” Symphylan Identification, Oregon State University, mint.ippc.orst.edu/symphid.htm.

Miyazawa, Hideyuki, et al. “Molecular Phylogeny of Myriapoda Provides Insights into Evolutionary Patterns of the Mode in Post-Embryonic Development.” Scientific Reports, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, doi:10.1038/srep04127.

[5] Tree of Life Web Project. 2002. Pauropoda. pauropods. Version 01 January 2002 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Pauropoda/2531/2002.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

[1]Haulter, Josh. “How Do I Create a BioActive Vivarium?” TheBioDude, 2 Jan. 2017, www.thebiodude.com/blogs/how-do-i-create-a-bioactive-vivarium.