Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

===Fruiting bodies=== | ===Fruiting bodies=== | ||

The most recognizable part of an EcM relationship is the fruiting body. These growths are usually easy to spot with the naked eye. The function of the fruiting body is sexual reproduction to spread the fungus to new hosts. | The most recognizable part of an EcM relationship is the fruiting body. These growths are usually easy to spot with the naked eye. The function of the fruiting body is sexual reproduction to spread the fungus to new hosts. | ||

==Symbiotic relationship with plant roots== | |||

==Role in spread of invasive species== | ==Role in spread of invasive species== | ||

Ectomycorrhizal fungi are more specialized in their formation of symbiotic relationships, so they are not hugely involved in the spread of non native species. That said, eucalypt and pine trees are obligate EcM trees and are often grown en masse on plantations, sometimes for commercial use. [5] | Ectomycorrhizal fungi are more specialized in their formation of symbiotic relationships, so they are not hugely involved in the spread of non native species. That said, eucalypt and pine trees are obligate EcM trees and are often grown en masse on plantations, sometimes for commercial use. [5] In New Zealand, ''Pinus contorta'' has gained a foothold in natural ecosystems with the help of EcM relationships [6] ''Pinus contorta'' is native to the western United States and now compete with co-ocurring with native Nothofagus solandri var. cliffortioides. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 29: | Line 36: | ||

[5] Díez, Jesús. "Invasion biology of Australian ectomycorrhizal fungi introduced with eucalypt plantations into the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Issues in Bioinvasion Science. 2005: 3–15. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3870-4_2. | [5] Díez, Jesús. "Invasion biology of Australian ectomycorrhizal fungi introduced with eucalypt plantations into the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Issues in Bioinvasion Science. 2005: 3–15. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3870-4_2. | ||

[6] Dickie, Ian A.; et al. (2010). "Co‐invasion by Pinus and its mycorrhizal fungi". New Phytologist. 187 (2): 475–484. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03277.x. PMID 20456067. | |||

[7] Egerton-Warburton, L. M.; et al. (2003). "Mycorrhizal fungi". Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment. | |||

Revision as of 10:43, 9 May 2018

Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi form symbiotic relationships with Plant roots. Only about 2% of the plant species on earth form endomycorrhizal relationships, but therein exist some of the most environmentally and economically important species. [1] EcM fungi tend towards specificity when choosing hosts, while Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi is much more generalized in its choosing.

Structures

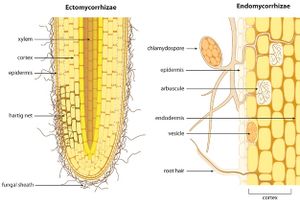

Mantle

A layer encasing the outside of the root tip in either a loose gathering or tight alignment of hyphae. The presence of the mantle can sometimes hinder root hair growth if the root is secured tightly.

Hartig net

A network of hyphae strands that work around epidermal and cortical root cells, as they make their way through the cortex towards the middle of the root. [4]

Extraradical hyphae

A fine network of hyphae that extend outward from the encased root, filling the role of the suppressed root hairs. By spreading out into the surrounding soil, the hyphae can extract water and nutrients for transport back to the root.

Fruiting bodies

The most recognizable part of an EcM relationship is the fruiting body. These growths are usually easy to spot with the naked eye. The function of the fruiting body is sexual reproduction to spread the fungus to new hosts.

Symbiotic relationship with plant roots

Role in spread of invasive species

Ectomycorrhizal fungi are more specialized in their formation of symbiotic relationships, so they are not hugely involved in the spread of non native species. That said, eucalypt and pine trees are obligate EcM trees and are often grown en masse on plantations, sometimes for commercial use. [5] In New Zealand, Pinus contorta has gained a foothold in natural ecosystems with the help of EcM relationships [6] Pinus contorta is native to the western United States and now compete with co-ocurring with native Nothofagus solandri var. cliffortioides.

References

[1] Tedersoo, Leho; May, Tom W.; Smith, Matthew E. (2010). "Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages" (PDF). Mycorrhiza. 20 (4): 217–263. doi:10.1007/s00572-009-0274-x. PMID 20191371.

[2] Dighton, J. "Mycorrhizae." Encyclopedia of Microbiology (2009): 153-162.

[3] Smith, Sally E.; Read, David J. (26 July 2010). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-055934-6.

[4] Carlile, M.J. & Watkinson, S.C. (1994) The Fungi. Academic Press Ltd, London. pp 329 - 340.

[5] Díez, Jesús. "Invasion biology of Australian ectomycorrhizal fungi introduced with eucalypt plantations into the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Issues in Bioinvasion Science. 2005: 3–15. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3870-4_2.

[6] Dickie, Ian A.; et al. (2010). "Co‐invasion by Pinus and its mycorrhizal fungi". New Phytologist. 187 (2): 475–484. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03277.x. PMID 20456067.

[7] Egerton-Warburton, L. M.; et al. (2003). "Mycorrhizal fungi". Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment.