Harvester Ant: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

== Anatomy == | == Anatomy == | ||

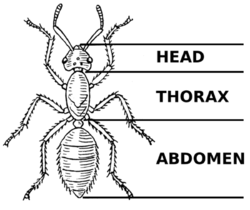

[[File:HTA.png|250px|thumb|left|Head, thorax, and abdomen.]] | |||

The Harvester Ant’s body is divided into three sections; the head, thorax, and abdomen. The ants’ exoskeleton is made of chitin and protects them from the elements and predators. <sup>[1]</sup> Harvester ants are moderately large with a size ranging between 5 and 10 mm. They are typically reddish-brown, however, some species are closer to brownish-black coloring. <sup>[4]</sup> | The Harvester Ant’s body is divided into three sections; the head, thorax, and abdomen. The ants’ exoskeleton is made of chitin and protects them from the elements and predators. <sup>[1]</sup> Harvester ants are moderately large with a size ranging between 5 and 10 mm. They are typically reddish-brown, however, some species are closer to brownish-black coloring. <sup>[4]</sup> | ||

Revision as of 22:15, 22 April 2023

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Genus: | Pogonomyrmex |

Pogonomyrmex is the genus of harvester ants; there are 95 different species of extant harvester ants. [5] Colonies can survive anywhere from 14-50 years and reach up to 10,000 workers. [4] The genus Pogonomyrmex is known for its habit of collecting seeds and other items. These ants are also known for their painful and venomous sting.

Anatomy

The Harvester Ant’s body is divided into three sections; the head, thorax, and abdomen. The ants’ exoskeleton is made of chitin and protects them from the elements and predators. [1] Harvester ants are moderately large with a size ranging between 5 and 10 mm. They are typically reddish-brown, however, some species are closer to brownish-black coloring. [4]

Head

Ants have a set of compound eyes, two antennae, powerful mandibles for carrying, cutting and biting, and maxillary palps to detect scent. [1] Harvester ants have another unique feature; a psammophore. A psammophore is a fringe of hair on the underside of the head that looks like a beard. These “beards” help to excavate nests by acting like a bulldozer. [4]

Thorax

The thorax is the middle segment of the ant and it contains three pairs of legs. The thorax also has a petiole which is the connection between the thorax and the abdomen.

Abdomen

The abdomen contains the ants' vital organs, reproductive parts, and stinger. The acidopore contains formic acid for the ant to emit when it feels threatened. [1] Harvester ants are violent when they feel threatened and their stings are very painful and sometimes dangerous. [5]

Habitat and Range

Pogonomyrmex is native to North, Central, and South America. [5] They construct their nests in the soil, typically in dry and sandy areas that are fully exposed to the sun. [4] They can be 1-10 m in diameter with tunnels that extend down to 5 m or more. [4] The nests can range from having no mound to having a huge mound; the latter tends to be more common. The entrances to the nests are often marked in a special way; by a crater or cone, a pile of stones, or a covering of gravel. [5] In addition, some species clear away all plants and vegetation that surround the outside area of the nest. [5]

Diet and Behavior

A harvester ants diet mainly consists of seeds. Given their name, the workers of this genus “harvest” the plants by snipping off seeds with their mandibles. The seeds are stored within chambers in the mound, enough to sustain the entire colony through the winter. [5] Although seeds are the main food source of harvester ants, they are also capable of being scavengers; arthropods are the most common victim, however, the ants also go for a variety of other dead organisms. [5] Worker ants are typically the ones who go out looking for the colony's food, however, three species of harvester ants display a unique behavior. Queens of the species P. cuni- cularius cunicularius, P. cunicularius pencosensis, and P. huachucanus all have been observed foraging for food in the field. Queens of P .hauchucanus are obligate foragers and the other two species are not. [3]

Another behavior of the harvester ant is its defense mechanism; stinging. When threatened, many species of Pogonomyrmex become violent and persistently sting the threat. The effects of the sting can be very painful and cause swelling and inflammation which can last several hours. Depending on one's sensitivity to the venom or the severity of the stings, medical attention may be needed. [5] For the size of a harvester ant, their sting is quite painful and potent. An additional distinctive behavior of the ant is that they move much slower than other similar species, such as fire ants. [4]

Life Cycle

Harvester ants mate from spring to fall each year, most frequently after summer rains. [6] Winged males and females swarm together to form “mating balls” where they pair and mate. Males die soon after, and females break off their wings and lay eggs after finding a suitable nesting site to start a new colony. [2] Larvae hatch from the eggs and develop through several stages, called instars. The larvae appear white and legless with a small but distinct head. The next stage is pupation, which occurs within a cocoon. Once worker ants are produced by the queen, they begin to care for the other developing ants, enlarge the nest, and forage for food. [6]

Ecological Impacts

Due to the seed-harvesting habit of these ants, they are often seen as agricultural pests. They reduce vegetation and can damage rangeland used for cattle grazing. On the other hand, they can have several benefits; they aerate the soil, provide enrichment, and promote new plants to sprout by discarding seeds. The ants also play an important role in structuring the ecosystem around them. Based on the quantity and type of seeds the ants are harvesting, their differential feeding can alter the composition of the plant community. [4]

References

[1] Body structure. 2021. . Harvard University. https://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu/ants/body-structure.

[2] Cranshaw, W. 2010, January 28. Harvester ants . Colorado State University. https://wiki.bugwood.org/HPIPM:Harvester_Ants.

[3] Johnson, R. A. 1970, January 1. Independent colony founding by ergatoid queens in the ant genus pogonomyrmex: Queen foraging provides an alternative to dependent colony founding: Semantic scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Independent-colony-founding-by-ergatoid-queens-in-Johnson/853f60e8e139782d87b154967845edcd792585f6.

[4] Pogonomyrmex. 2019. . https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/pogonomyrmex.

[5] Shattuck, S. 2023, April 9. Pogonomyrmex. https://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Pogonomyrmex.

[6] Vinson, B. S., and J. Jackman. 2018, August 1. Red Harvester Ant . Texas A&M University. https://extensionentomology.tamu.edu/insects/red-harvester-ant/.