American Bullfrog: Difference between revisions

Created page with "== Taxonomy == {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width:80%;" |+ American Bullfrog Taxonomy |- | ! scope="row" | Kingdom ! scope="row" | Phylum ! scope="row" | C..." |

|||

| (67 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''Lithobates catesbeianus'', or the American Bullfrog as it is more commonly known, is a member of the true frog family native to Eastern North America. With its large size compared to other frog species, the species is able to inhabit a wide variety of aquatic environments with relative success. The American Bullfrog gets its name from the male call during breeding season resembling a bull's bellow. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; float:right; margin-left: 10px; | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width: | |+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb(235,235,210)|'''Scientific Classification''' | ||

| | |- | ||

| [[File:American bullfrog adult male.jpg| 300px]] | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Kingdom: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |[[Animals|Animalia]] | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Subkingdom: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Bilateria | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Infrakingdom: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Deuterostomia | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Phylum: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Chordata | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Subphylum: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Vertebrata | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Infraphylum: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Gnathostomata | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Superclass: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Tetrapoda | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Class: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Amphibia | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Order: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Anura | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Family: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |Ranidea | |||

|- | |||

!style="min-width:6em; |Genus: | |||

|style="min-width:6em; |''Lithobates'' | |||

|- | |- | ||

!style="min-width:6em; |Species: | |||

! | |style="min-width:6em; |''L. catesbeianus'' | ||

|- | |- | ||

|colspan="2" |Source: Integrated Taxonomic Information System <ref name="ITIS">[https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=977384#null "Integrated Taxonomic Information System - Report"], ''ITIS'' USGS Open-File Report 2006-1195: Nomenclature", ''USGS'', n.d.. Retrieved 3/10/2023.</ref> | |||

|} | |} | ||

== '''Description''' == | |||

The American Bullfrog has an olive-green coloring on the dorsal surface (backside) which may also include dull brown mottling or banding patterns ending at the top lip. The ventral surface (belly) typically appears as an off-white color with gray or yellow blotchy patches that end at the bottom lip. They can grow up to 0.5 kg (1.1 lbs.) in weight and between 90-152 mm (3.5-6 in) in length.<ref>Bruening, S. 2002. "Lithobates catesbeianus" (On-line), Animal [[Diversity]] Web. Accessed March 10, 2023 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Lithobates_catesbeianus/</ref> American Bullfrogs possess extremely small teeth that only function to grasp objects. The eyes notably have horizontal pupils and a brownish iris. The tympanum (external eardrum) is right behind the eyes and is enclosed with thin skin to pick up sound and vibrations. The hind legs are long and possess webbing between the toes while the frontal legs are shorter and are un-webbed. | |||

The American Bullfrog displays sexual dimorphism, physical differences between sexes. Female bullfrogs have a smaller tympanum than males. Males typically have a tympanum that is larger than the eye and female tympanum are about the same size as the eye. You can also tell the differences between sexes from the color of the throat. Males tend to have bright, yellow-colored throats while females usually have cream or pale white colored throats.<ref>Asahara, Masakazu et al. “Sexual dimorphism in external morphology of the American bullfrog Rana (Aquarana) catesbeiana and the possibility of sex determination based on tympanic membrane/eye size ratio.” The Journal of veterinary medical science vol. 82,8 (2020): 1160-1164. doi:10.1292/jvms.20-0039</ref> | |||

== '''Range and Habitat''' == | |||

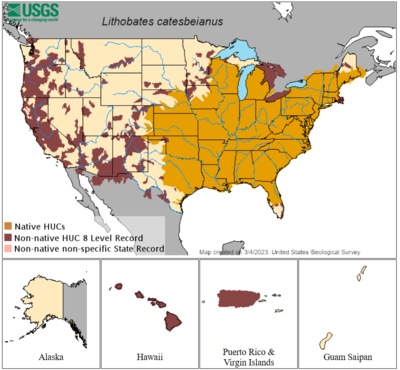

[[File:American bullfrog range.PNG| 400px | border | Native and Introduced Range |]] | |||

=== Range === | |||

The American Bullfrog is native to the eastern part of North America. Its range extends as far north as Nova Scotia to as south as Florida, from the Atlantic coast to as far west as Kansas. They have been introduced to western parts of North America like Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, California, Oregon, Arizona, Utah, and Washington. They have also been introduced to Mexico, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. They have also been introduced into Europe (Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, France), Asia (India, China, South Korea, Japan), and other countries such as the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Cuba. <ref>Liz McKercher, and Denise R. Gregoire, 2023, Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=71, Revision Date: 12/2/2022, Access Date: 3/10/2023</ref> Possible reasons for introduction include intentionally using them as biological control agents or as a source of food. People who own them as pets may also release them intentionally. | |||

=== Habitat === | |||

American Bullfrogs live in or near areas of water like lakes, ponds, swamps, marshes, streams, and rivers. They prefer warm, still, and shallow freshwater with lots of vegetation. Bullfrogs are somewhat tolerant of colder temperatures and can hibernate in mud and the bottom layer underwater during freezing temperatures. | |||

== '''Reproduction''' == | |||

The American Bullfrog breeding season takes place only once a year during the end of spring into summer, from May to July. Males arrive at the breeding sites first before the females arrive. Male bullfrogs group together in clusters called choruses. <ref>Emlen, Stephen T. “Lek Organization and Mating Strategies in the Bullfrog.” Behavioral [[Ecology]] and Sociobiology, vol. 1, no. 3, 1976, pp. 283–313, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300069.</ref> Female bullfrogs find choruses to be more attractive. Males have more than one mate, so choruses are constantly breaking apart and reforming, with different male individuals. Male bullfrogs have three different calls during this time. A territorial call that warns other males, a confrontational call that usually happens right before a fight, and a mating call to attract females. <ref>Wiewandt, Thomas A. “Vocalization, Aggressive Behavior, and Territoriality in the Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana.” Copeia, vol. 1969, no. 2, 1969, pp. 276–85, https://doi.org/10.2307/1442074.</ref> When a female picks a male, she moves into his territory to lay her eggs. The male will simultaneously release sperm while the female lays a clutch of about 20,000 eggs. This is a form of external fertilization, <ref>LANNOO, MICHAEL, et al. “Introduction.” Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species, edited by MICHAEL LANNOO, 1st ed., University of California Press, 2005, pp. 351–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pp5xd.59. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.</ref> where the eggs are fertilized outside of the female body. | |||

== '''Growth and Development''' == | |||

American Bullfrog tadpoles hatch four to five days after fertilization. Adults do not have parental investment once they hatch, and the tadpoles must survive on their own. Hatched in fresh water, tadpoles remain in the shallows and as they develop, move to deeper water. Tadpoles have three pairs of external gills and multiple rows of teeth on the lips. As they develop, they grow downward-facing mouths and tails with broad dorsal and ventral fins. <ref>Stebbins, Robert C., and Nathan W. Cohen. “Reproduction.” A Natural History of Amphibians, Princeton University Press, 1995, pp. 140–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nxcv5j.21. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.</ref> They start using their teeth to eat bigger particles of food. It can take approximately three years for a tadpole to develop into an adult frog. Female and male frogs reach sexual maturity at three to five years of age. A bullfrog can live up to seven to ten years in the wild. | |||

[[File:American bullfrog tadpole.jpg| 250px ]] | |||

== '''Diet''' == | |||

The American Bullfrog is a carnivore and is known to eat a variety of [[organisms]] including [[invertebrates]] such as snails, crustaceans, worms, mollusks, and [[insects]]. However, due to the opportunistic behavior of the American Bullfrog, they have been found to eat species of rodents, small snakes, and birds. They can be cannibalistic and eat frogs, tadpoles, and the eggs of fish or [[salamanders]]. Tadpoles mostly eat aquatic plants and [[algae]] and will eat larger portions as they grow. | |||

=== '''Feeding''' === | |||

American Bullfrogs are observed to be ambush and opportunistic predators, feeding on a variety of [[animals]] unsuspecting of their presence. Once the prey has been spotted, the bullfrog will move towards the prey using a series of hops to sneak up on its prey. The bullfrog uses its tongue to catch the prey and takes a bite from its strong jaw. Smaller prey is then consumed and engulfed using its mouth. American Bullfrogs have been observed to use their front legs as hands to assist in eating larger prey that are not able to fit inside the mouth. Bullfrogs are observed to asphyxiate larger prey after a successful catch as a defense mechanism. This behavior mimics other forms of feeding from other frogs, most notably | |||

a [[wood frog]].<ref>Cardini, F. (1974). Specializations of the Feeding Response of the Bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, for the Capture of Prey Submerged in Water. M.S. Thesis, U. of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA</ref> | |||

== '''Predators''' == | |||

American Bullfrogs are an essential prey item for many birds, predatory fish, otters, and other amphibians. Herons like the Great Blue Heron and Great Egrets, smaller birds like the common and belted kingfisher, turtles, water snakes and raccoons are also predators. American Bullfrog eggs are famously bad tasting to many predators that typically consume frog and fish eggs as part of their diet. Tadpoles are not eaten by predators because they have an undesirable taste. However, predators that aren't deterred by the taste tend to have an easier time spotting out Bullfrog tadpoles due to their activity. Bullfrogs tend to be loud when attacked by a predator, warning other bullfrogs in the area to the potential danger and many will retreat to deeper water. | |||

== '''Invasion ''' == | |||

The American Bullfrog is an invasive species that was brought up into the Western United States in the early 1900s. The American Bullfrog was introduced via escapes from aquaculture, intentional releases from research facilities and pets being rereleased into the wild. As bullfrogs began to invade these new ecosystems they began to spread diseases, create more competition for native species, cause damage to ecosystems and farm crops, and potentially hurting the quality of our drinking water. <ref>"American Bullfrog"https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/fish-and-other-vertebrates/american-bullfrog</ref> | |||

== '''Management ''' == | |||

=== Problem === | |||

Introduced bullfrogs in non-native ranges are now a concern for the native species in that range. They are highly adaptable and have a high reproductive rate. The Bullfrog has both a direct and indirect effect on native species, like native birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, through competition, predation, habitat alteration and displacement. They also have negative effects on some aquatic snakes and waterfowl. There is also a concern that the bullfrog is a possible carrier for a chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which is fatal for some amphibians. <ref>Adams, Michael J., and Christopher A. Pearl. “Problems and Opportunities Managing Invasive Bullfrogs: Is There Any Hope?” Biological Invaders in Inland Waters: Profiles, Distribution, and Threats, Springer Netherlands, pp. 679–93, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6029-8_38.</ref> | |||

=== Solution === | |||

Some management options for Bullfrogs are direct removal, adults being caught in traps or hand captures, and tadpoles by draining ponds or chemical treatment. The use of funnel traps, gigs, guns, and fencing off a pond are some other methods that are used. A third management option is habitat manipulation. The use of chemical control and toxicants as a management option is a possibility but needs more experiments and testing to not affect the entire aquatic ecosystem. <ref>Snow, N. P, & Witmer, G. (2010). American Bullfrogs as Invasive Species: A Review of the Introduction, Subsequent Problems, Management Options, and Future Directions. Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/V424110490 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5j46t7f2</ref> | |||

== '''References''' == | |||

<ref>Emlen, Stephen T. “Territoriality in the Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana.” Copeia, vol. 1968, no. 2, 1968, pp. 240–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/1441748.</ref> | |||

<ref>Ryan, Michael J. “The Reproductive Behavior of the Bullfrog (Rana Catesbeiana).” Copeia, vol. 1980, no. 1, 1980, pp. 108–14, https://doi.org/10.2307/1444139.</ref> | |||

<ref>Korschgen, Leroy J., and Thomas S. Baskett. “Foods of Impoundment- and Stream-Dwelling Bullfrogs in Missouri.” Herpetologica, vol. 19, no. 2, 1963, pp. 89–99. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3890543. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.</ref> | |||

<ref>HIRAI, Toshiaki. “Diet Composition of Introduced Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana, in the Mizorogaike Pond of Kyoto, Japan.” Ecological Research, vol. 19, no. 4, 2004, pp. 375–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1703.2004.00647.x.</ref> | |||

<ref>“American Bullfrog.” NatureMapping, http://naturemappingfoundation.org/natmap/facts/american_bullfrog_k6.html#:~:text=The%20male%20and%20female%20bullfrogs,much%20larger%20than%20the%20eye.</ref> | |||

<ref>“California's Invaders: American Bullfrog.” California Department of Fish and Wildlife, https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Invasives/Species/Bullfrog#:~:text=American%20bullfrogs%20occupy%20a%20wide,lakes%20and%20banks%20of%20streams.</ref> | |||

<ref>“American Bullfrog.” National Aquarium, https://aqua.org/explore/animals/american-bullfrog#:~:text=During%20the%20cold%20winter%20season,portions%20of%20streams%20and%20rivers.</ref> | |||

<ref>“Eggs, Tadpoles and Development of American Bullfrog - Lithobates Catesbeianus.” Californiaherps.com, Reptiles and Amphibians of California, https://californiaherps.com/frogs/pages/l.catesbeianus.tadpoles.html.</ref> | |||

<ref>"American Bullfrog"https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/fish-and-other-vertebrates/american-bullfrog</ref> | |||

Latest revision as of 13:25, 9 May 2025

Lithobates catesbeianus, or the American Bullfrog as it is more commonly known, is a member of the true frog family native to Eastern North America. With its large size compared to other frog species, the species is able to inhabit a wide variety of aquatic environments with relative success. The American Bullfrog gets its name from the male call during breeding season resembling a bull's bellow.

| |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Subkingdom: | Bilateria |

| Infrakingdom: | Deuterostomia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Superclass: | Tetrapoda |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Ranidea |

| Genus: | Lithobates |

| Species: | L. catesbeianus |

| Source: Integrated Taxonomic Information System [1] | |

Description

The American Bullfrog has an olive-green coloring on the dorsal surface (backside) which may also include dull brown mottling or banding patterns ending at the top lip. The ventral surface (belly) typically appears as an off-white color with gray or yellow blotchy patches that end at the bottom lip. They can grow up to 0.5 kg (1.1 lbs.) in weight and between 90-152 mm (3.5-6 in) in length.[2] American Bullfrogs possess extremely small teeth that only function to grasp objects. The eyes notably have horizontal pupils and a brownish iris. The tympanum (external eardrum) is right behind the eyes and is enclosed with thin skin to pick up sound and vibrations. The hind legs are long and possess webbing between the toes while the frontal legs are shorter and are un-webbed.

The American Bullfrog displays sexual dimorphism, physical differences between sexes. Female bullfrogs have a smaller tympanum than males. Males typically have a tympanum that is larger than the eye and female tympanum are about the same size as the eye. You can also tell the differences between sexes from the color of the throat. Males tend to have bright, yellow-colored throats while females usually have cream or pale white colored throats.[3]

Range and Habitat

Range

The American Bullfrog is native to the eastern part of North America. Its range extends as far north as Nova Scotia to as south as Florida, from the Atlantic coast to as far west as Kansas. They have been introduced to western parts of North America like Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, California, Oregon, Arizona, Utah, and Washington. They have also been introduced to Mexico, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. They have also been introduced into Europe (Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, France), Asia (India, China, South Korea, Japan), and other countries such as the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Cuba. [4] Possible reasons for introduction include intentionally using them as biological control agents or as a source of food. People who own them as pets may also release them intentionally.

Habitat

American Bullfrogs live in or near areas of water like lakes, ponds, swamps, marshes, streams, and rivers. They prefer warm, still, and shallow freshwater with lots of vegetation. Bullfrogs are somewhat tolerant of colder temperatures and can hibernate in mud and the bottom layer underwater during freezing temperatures.

Reproduction

The American Bullfrog breeding season takes place only once a year during the end of spring into summer, from May to July. Males arrive at the breeding sites first before the females arrive. Male bullfrogs group together in clusters called choruses. [5] Female bullfrogs find choruses to be more attractive. Males have more than one mate, so choruses are constantly breaking apart and reforming, with different male individuals. Male bullfrogs have three different calls during this time. A territorial call that warns other males, a confrontational call that usually happens right before a fight, and a mating call to attract females. [6] When a female picks a male, she moves into his territory to lay her eggs. The male will simultaneously release sperm while the female lays a clutch of about 20,000 eggs. This is a form of external fertilization, [7] where the eggs are fertilized outside of the female body.

Growth and Development

American Bullfrog tadpoles hatch four to five days after fertilization. Adults do not have parental investment once they hatch, and the tadpoles must survive on their own. Hatched in fresh water, tadpoles remain in the shallows and as they develop, move to deeper water. Tadpoles have three pairs of external gills and multiple rows of teeth on the lips. As they develop, they grow downward-facing mouths and tails with broad dorsal and ventral fins. [8] They start using their teeth to eat bigger particles of food. It can take approximately three years for a tadpole to develop into an adult frog. Female and male frogs reach sexual maturity at three to five years of age. A bullfrog can live up to seven to ten years in the wild.

Diet

The American Bullfrog is a carnivore and is known to eat a variety of organisms including invertebrates such as snails, crustaceans, worms, mollusks, and insects. However, due to the opportunistic behavior of the American Bullfrog, they have been found to eat species of rodents, small snakes, and birds. They can be cannibalistic and eat frogs, tadpoles, and the eggs of fish or salamanders. Tadpoles mostly eat aquatic plants and algae and will eat larger portions as they grow.

Feeding

American Bullfrogs are observed to be ambush and opportunistic predators, feeding on a variety of animals unsuspecting of their presence. Once the prey has been spotted, the bullfrog will move towards the prey using a series of hops to sneak up on its prey. The bullfrog uses its tongue to catch the prey and takes a bite from its strong jaw. Smaller prey is then consumed and engulfed using its mouth. American Bullfrogs have been observed to use their front legs as hands to assist in eating larger prey that are not able to fit inside the mouth. Bullfrogs are observed to asphyxiate larger prey after a successful catch as a defense mechanism. This behavior mimics other forms of feeding from other frogs, most notably a wood frog.[9]

Predators

American Bullfrogs are an essential prey item for many birds, predatory fish, otters, and other amphibians. Herons like the Great Blue Heron and Great Egrets, smaller birds like the common and belted kingfisher, turtles, water snakes and raccoons are also predators. American Bullfrog eggs are famously bad tasting to many predators that typically consume frog and fish eggs as part of their diet. Tadpoles are not eaten by predators because they have an undesirable taste. However, predators that aren't deterred by the taste tend to have an easier time spotting out Bullfrog tadpoles due to their activity. Bullfrogs tend to be loud when attacked by a predator, warning other bullfrogs in the area to the potential danger and many will retreat to deeper water.

Invasion

The American Bullfrog is an invasive species that was brought up into the Western United States in the early 1900s. The American Bullfrog was introduced via escapes from aquaculture, intentional releases from research facilities and pets being rereleased into the wild. As bullfrogs began to invade these new ecosystems they began to spread diseases, create more competition for native species, cause damage to ecosystems and farm crops, and potentially hurting the quality of our drinking water. [10]

Management

Problem

Introduced bullfrogs in non-native ranges are now a concern for the native species in that range. They are highly adaptable and have a high reproductive rate. The Bullfrog has both a direct and indirect effect on native species, like native birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, through competition, predation, habitat alteration and displacement. They also have negative effects on some aquatic snakes and waterfowl. There is also a concern that the bullfrog is a possible carrier for a chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which is fatal for some amphibians. [11]

Solution

Some management options for Bullfrogs are direct removal, adults being caught in traps or hand captures, and tadpoles by draining ponds or chemical treatment. The use of funnel traps, gigs, guns, and fencing off a pond are some other methods that are used. A third management option is habitat manipulation. The use of chemical control and toxicants as a management option is a possibility but needs more experiments and testing to not affect the entire aquatic ecosystem. [12]

References

[13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

- ↑ "Integrated Taxonomic Information System - Report", ITIS USGS Open-File Report 2006-1195: Nomenclature", USGS, n.d.. Retrieved 3/10/2023.

- ↑ Bruening, S. 2002. "Lithobates catesbeianus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed March 10, 2023 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Lithobates_catesbeianus/

- ↑ Asahara, Masakazu et al. “Sexual dimorphism in external morphology of the American bullfrog Rana (Aquarana) catesbeiana and the possibility of sex determination based on tympanic membrane/eye size ratio.” The Journal of veterinary medical science vol. 82,8 (2020): 1160-1164. doi:10.1292/jvms.20-0039

- ↑ Liz McKercher, and Denise R. Gregoire, 2023, Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=71, Revision Date: 12/2/2022, Access Date: 3/10/2023

- ↑ Emlen, Stephen T. “Lek Organization and Mating Strategies in the Bullfrog.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 1, no. 3, 1976, pp. 283–313, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300069.

- ↑ Wiewandt, Thomas A. “Vocalization, Aggressive Behavior, and Territoriality in the Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana.” Copeia, vol. 1969, no. 2, 1969, pp. 276–85, https://doi.org/10.2307/1442074.

- ↑ LANNOO, MICHAEL, et al. “Introduction.” Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species, edited by MICHAEL LANNOO, 1st ed., University of California Press, 2005, pp. 351–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pp5xd.59. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

- ↑ Stebbins, Robert C., and Nathan W. Cohen. “Reproduction.” A Natural History of Amphibians, Princeton University Press, 1995, pp. 140–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nxcv5j.21. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

- ↑ Cardini, F. (1974). Specializations of the Feeding Response of the Bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, for the Capture of Prey Submerged in Water. M.S. Thesis, U. of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA

- ↑ "American Bullfrog"https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/fish-and-other-vertebrates/american-bullfrog

- ↑ Adams, Michael J., and Christopher A. Pearl. “Problems and Opportunities Managing Invasive Bullfrogs: Is There Any Hope?” Biological Invaders in Inland Waters: Profiles, Distribution, and Threats, Springer Netherlands, pp. 679–93, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6029-8_38.

- ↑ Snow, N. P, & Witmer, G. (2010). American Bullfrogs as Invasive Species: A Review of the Introduction, Subsequent Problems, Management Options, and Future Directions. Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/V424110490 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5j46t7f2

- ↑ Emlen, Stephen T. “Territoriality in the Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana.” Copeia, vol. 1968, no. 2, 1968, pp. 240–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/1441748.

- ↑ Ryan, Michael J. “The Reproductive Behavior of the Bullfrog (Rana Catesbeiana).” Copeia, vol. 1980, no. 1, 1980, pp. 108–14, https://doi.org/10.2307/1444139.

- ↑ Korschgen, Leroy J., and Thomas S. Baskett. “Foods of Impoundment- and Stream-Dwelling Bullfrogs in Missouri.” Herpetologica, vol. 19, no. 2, 1963, pp. 89–99. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3890543. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

- ↑ HIRAI, Toshiaki. “Diet Composition of Introduced Bullfrog, Rana Catesbeiana, in the Mizorogaike Pond of Kyoto, Japan.” Ecological Research, vol. 19, no. 4, 2004, pp. 375–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1703.2004.00647.x.

- ↑ “American Bullfrog.” NatureMapping, http://naturemappingfoundation.org/natmap/facts/american_bullfrog_k6.html#:~:text=The%20male%20and%20female%20bullfrogs,much%20larger%20than%20the%20eye.

- ↑ “California's Invaders: American Bullfrog.” California Department of Fish and Wildlife, https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Invasives/Species/Bullfrog#:~:text=American%20bullfrogs%20occupy%20a%20wide,lakes%20and%20banks%20of%20streams.

- ↑ “American Bullfrog.” National Aquarium, https://aqua.org/explore/animals/american-bullfrog#:~:text=During%20the%20cold%20winter%20season,portions%20of%20streams%20and%20rivers.

- ↑ “Eggs, Tadpoles and Development of American Bullfrog - Lithobates Catesbeianus.” Californiaherps.com, Reptiles and Amphibians of California, https://californiaherps.com/frogs/pages/l.catesbeianus.tadpoles.html.

- ↑ "American Bullfrog"https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/fish-and-other-vertebrates/american-bullfrog