Coleoptera: Difference between revisions

m The LinkTitles extension automatically added links to existing pages (<a rel="nofollow" class="external free" href="https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles">https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles</a>). |

m The LinkTitles extension automatically added links to existing pages (https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles). |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The thorax of the beetle is made up of the abdomen, elytra, hind wings, and six legs. The segmented legs are dedicated primarily to easy and rapid locomotion, but also facilitate in grooming, traction, and sometimes protection. Based on the species, the legs can be specialized for running, swimming, jumping, or digging.[3] One of coleoptera’s most distinguishing features is their elytron. Elytra are the hardened forewings, and are the reason for their formal name. Koleos means sheath, and pteron means wing. These wings meet down a line down the middle of their backs and work in conjuction with their exoskeleton to protect their hind wings and their abdomen.[1] These wings extend outward at 90 degree angles when in flight, revealing the membranous hind wings. Elytras vary in color for camouflage, reflecting heat, or warnings to predators. | The thorax of the beetle is made up of the abdomen, elytra, hind wings, and six legs. The segmented legs are dedicated primarily to easy and rapid locomotion, but also facilitate in grooming, traction, and sometimes protection. Based on the species, the legs can be specialized for running, swimming, jumping, or digging.[3] One of coleoptera’s most distinguishing features is their elytron. Elytra are the hardened forewings, and are the reason for their formal name. Koleos means sheath, and pteron means wing. These wings meet down a line down the middle of their backs and work in conjuction with their exoskeleton to protect their hind wings and their abdomen.[1] These wings extend outward at 90 degree angles when in flight, revealing the membranous hind wings. Elytras vary in color for camouflage, reflecting heat, or warnings to predators. | ||

The abdomen of beetles is comprised of nine or ten segments and contains their organs for digestion, breathing, and reproduction.[4] On some beetles, such as the tiger beetle, the abdomen hosts ears to hear predators, such as bats. Coleoptera have an open circulatory system, meaning they do not have veins or arteries. Tiny pumps inside the beetle send hemolymph (blood of invertebrates) throughout the segmented body. The hemolymph transports nutrients and waste, however it does not aid in oxygen uptake.[3] | The abdomen of beetles is comprised of nine or ten segments and contains their organs for digestion, breathing, and reproduction.[4] On some beetles, such as the tiger beetle, the abdomen hosts ears to hear predators, such as bats. Coleoptera have an open circulatory system, meaning they do not have veins or arteries. Tiny pumps inside the beetle send hemolymph (blood of [[invertebrates]]) throughout the segmented body. The hemolymph transports nutrients and waste, however it does not aid in oxygen uptake.[3] | ||

==Diet== | ==Diet== | ||

[[File:miningleafbeetle.jpg|thumb|An adult female mining leaf beetle (''manoxia elegans''). They can be found in the western United States living among desert plants.[7] ]] | [[File:miningleafbeetle.jpg|thumb|An adult female mining leaf beetle (''manoxia elegans''). They can be found in the western United States living among desert plants.[7] ]] | ||

Coleoptera eat a wide variety of foods, depending on if they are herbivores or omnivores. Most species are herbivores and feed on roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Many omnivorous species are predatory, and will hide in [[soil]] or on vegetation and will attack invertebrates. Other species are scavengers and feed on decaying flesh or wood, fecal matter, and other dead organic matter. A few species are parasitic; they invade nests of ants or termites, invade hosts internally, or feed externally off mammals.[https://projects.ncsu.edu/cals/course/ent425/library/compendium/coleoptera.html] It is evident that due to the vast range of species and habitats, beetles’ diets vary just as widely. | Coleoptera eat a wide variety of foods, depending on if they are herbivores or omnivores. Most species are herbivores and feed on roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Many omnivorous species are predatory, and will hide in [[soil]] or on vegetation and will attack invertebrates. Other species are scavengers and feed on decaying flesh or wood, fecal matter, and other dead [[Organic Matter|organic matter]]. A few species are parasitic; they invade nests of ants or [[termites]], invade hosts internally, or feed externally off mammals.[https://projects.ncsu.edu/cals/course/ent425/library/compendium/coleoptera.html] It is evident that due to the vast range of species and habitats, beetles’ diets vary just as widely. | ||

==Habitat and Ecology== | ==Habitat and Ecology== | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

'''[[Ecology]]''' | '''[[Ecology]]''' | ||

Coleoptera serve several important functions within the animal kingdom. Similar to [[insects]], they provide food for larger animals such as birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians, and mammals. Many species such as cantharids, scarabs, byturids, and others, are pollinators, while other species like the dung beetle remove millions of tons of dung that would suffocate the land. They also aid in the breakdown of carcasses, with some species helping to control the populations of parasites like ticks and [[mites]]. Ladybugs for instance, control the populations of aphids and scale insects, which could prevent the destruction of crops.[http://www.coleoptera.org/p1058.htm] | Coleoptera serve several important functions within the animal kingdom. Similar to [[insects]], they provide food for larger animals such as birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians, and mammals. Many species such as cantharids, scarabs, byturids, and others, are pollinators, while other species like the [[Dung Beetle|dung beetle]] remove millions of tons of dung that would suffocate the land. They also aid in the breakdown of carcasses, with some species helping to control the populations of parasites like ticks and [[mites]]. Ladybugs for instance, control the populations of aphids and scale insects, which could prevent the destruction of crops.[http://www.coleoptera.org/p1058.htm] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[1] Maddison, David R. 2000. Coleoptera. Beetles. Version 11 September 2000. http://tolweb.org/Coleoptera/8221/2000.09.11 in The Tree of Life Web Project | [1] Maddison, David R. 2000. Coleoptera. Beetles. Version 11 September 2000. http://tolweb.org/Coleoptera/8221/2000.09.11 in The Tree of Life Web Project | ||

Latest revision as of 13:44, 1 May 2025

Coleoptera, known as beetles, are a diverse taxonomic order that includes almost 400,000 species making it the largest order in the animal kingdom. Coleoptera can be found on all continents except Antarctica, having the highest diversity in tropical zones where water and nutrients are abundant.[1] They are of the kingdom Animalia, the phylum Anthropoda, subphylum Hexapoda, and the class of Insecta. Almost all beetles undergo complete metamorphism, which, in addition to the elytron, are their most distinctive features. With a high variety of species, habitats, and diets, beetles can be found virtually anywhere on Earth.

Characteristics

Coleoptera are a highly diverse order, with all members undergoing a complete metamorphosis. The metamorphosis describes the process of the beetle undergoing four life-stages. These include the egg or embryo, the larva, the pupa, which is the resting or transformative stage, and finally imago, which is the adult or sexual stage. Animals that undergo complete metamorphism are called holometabolous.[2]

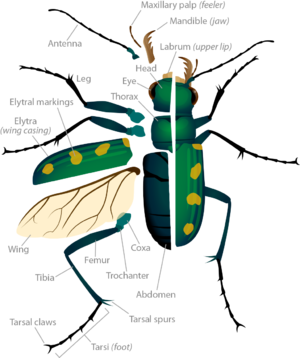

The anatomy of beetles is very similar to other arthropods, consisting of a head, thorax and abdomen, however these segments are differentiated and help to classify beetles. Unlike other arthropods, coleopteras have their mesothorax and metathorax attached to the abdomen. The third segment, prothorax, is isolated between the head and lower body, and is covered by a dorsal plate called the pronotum.[3]

The head consists of simple single-lens eyes, which are very sensitive to movement.[4] Their antennae serve to establish their surroundings and find food. They can touch, hear, taste, smell, feel temperature, and determine humidity. Strong mandibles serve as their jaw to breakdown food, and for some species they are used to fight off or intimidate predators and competition. Their head also holds their brain and mandibular muscles.[4]

The thorax of the beetle is made up of the abdomen, elytra, hind wings, and six legs. The segmented legs are dedicated primarily to easy and rapid locomotion, but also facilitate in grooming, traction, and sometimes protection. Based on the species, the legs can be specialized for running, swimming, jumping, or digging.[3] One of coleoptera’s most distinguishing features is their elytron. Elytra are the hardened forewings, and are the reason for their formal name. Koleos means sheath, and pteron means wing. These wings meet down a line down the middle of their backs and work in conjuction with their exoskeleton to protect their hind wings and their abdomen.[1] These wings extend outward at 90 degree angles when in flight, revealing the membranous hind wings. Elytras vary in color for camouflage, reflecting heat, or warnings to predators.

The abdomen of beetles is comprised of nine or ten segments and contains their organs for digestion, breathing, and reproduction.[4] On some beetles, such as the tiger beetle, the abdomen hosts ears to hear predators, such as bats. Coleoptera have an open circulatory system, meaning they do not have veins or arteries. Tiny pumps inside the beetle send hemolymph (blood of invertebrates) throughout the segmented body. The hemolymph transports nutrients and waste, however it does not aid in oxygen uptake.[3]

Diet

Coleoptera eat a wide variety of foods, depending on if they are herbivores or omnivores. Most species are herbivores and feed on roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Many omnivorous species are predatory, and will hide in soil or on vegetation and will attack invertebrates. Other species are scavengers and feed on decaying flesh or wood, fecal matter, and other dead organic matter. A few species are parasitic; they invade nests of ants or termites, invade hosts internally, or feed externally off mammals.[5] It is evident that due to the vast range of species and habitats, beetles’ diets vary just as widely.

Habitat and Ecology

Habitat

Coleoptera habituate all terrestrial and fresh-water environments, and are most abundant in the tropical regions of the lower latitudes. Depending on the beetle species they may live on fungi, burrow into plants, or dig tunnels into wood and trees.[5]

Coleoptera serve several important functions within the animal kingdom. Similar to insects, they provide food for larger animals such as birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians, and mammals. Many species such as cantharids, scarabs, byturids, and others, are pollinators, while other species like the dung beetle remove millions of tons of dung that would suffocate the land. They also aid in the breakdown of carcasses, with some species helping to control the populations of parasites like ticks and mites. Ladybugs for instance, control the populations of aphids and scale insects, which could prevent the destruction of crops.[6]

References

[1] Maddison, David R. 2000. Coleoptera. Beetles. Version 11 September 2000. http://tolweb.org/Coleoptera/8221/2000.09.11 in The Tree of Life Web Project

[2] Bartlett, Troy. “Order Coleoptera - Beetles.” Order Coleoptera - Beetles - BugGuide.Net, 2004, http://bugguide.net/node/view/60.

[3] “Beetles - Beetle Anatomy And Physiology.” Beetle Anatomy And Physiology - Legs, Pair, Called, and Hemolymph - JRank Articles, 2019, http://science.jrank.org/pages/808/Beetles-Beetle-anatomy-physiology.html.

[4] Nancy Pearson, Dave Pearson. "Tiger Beetle Anatomy". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 05 Feb 2015. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 15 Apr 2019. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tiger-beetle-anatomy

[5] Meyer, John R. “Classification & Distribution.” ENT 425 | General Entomology | Resource Library | Compendium [Coleoptera], 2016, http://projects.ncsu.edu/cals/course/ent425/library/compendium/coleoptera.html.

[6] Kaplan, Lawrence. “What Is the Beetle.” Coleoptera, 2018, http://www.coleoptera.org/p1058.htm.

[7] Plagens, Michael J. “Sonoran Desert Coleoptera (Beetles).” Beetles in the in the Sonoran Desert, http://www.arizonensis.org/sonoran/fieldguide/arthropoda/coleoptera.html.