Annelids: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m The LinkTitles extension automatically added links to existing pages (https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles). |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Annelids, or segmented worms, are segmented bilaterian [[invertebrates]] that are very important to a variety of marine and terrestrial environments. All annelids have a central body cavity called a coelom, bristles called setae, and segments called annulations which they are named after. There are three major groups of of annelids; the class Polychaeta which are almost entirely marine in nature and the subclasses of Oligochaeta which are earthworms and their relatives, and Hirudinea which are leeches. Among these groups there are approximately 17,000 described species. Many of the species of annelids reproduce sexually and are hermaphroditic, but some are able to asexually reproduce. Annelids are found across the entire planet in almost every kind of environment imaginable. Annelids are generally soft tissue organisms, but there is evidence of them in the fossil record dating back to the Ordovician period.[[File:Annelida.png|800px|thumb|right|]] | |||

== Classification == | == Classification == | ||

[[File:Leech.jpg|200px|thumb|left| ''Haemadipsa picta'' or the Tiger Leech member of the hirundinea subclass]] | |||

Annelids belong to the clade Lophotrochozoa. This clade also includes the phyla Mollusca, Sipuncula, Brachiopodia, and Phorondia. [1] The two major groups of annelids are the clitellates and polychaetes. Clitellates include members of the subclasses oligochaeta (eg. earthworms) and hirundinea (leeches). Oligochaetea are primarily terestrial, preferring damp soil, while leeches are mostly made up of freshwater aquatic species. | |||

Polychaetes are almost entirely made up of marine species, but a few freshwater species do exist.[1] There are abut 17,000 species of annelid and about 12,000 of them are members of polychaetes. Polychaetes are then divided into two groups dependent on if they are mostly mobile throughout life or if they live in tubes or burrows for the majority of their existence. There are also about 42 different groups of clitellates[2]. | |||

== Distribution and Habitat == | == Distribution and Habitat == | ||

Annelids, due to their incredible [[diversity]], live in nearly every habitat on planet, however they have no means of protecting themselves from desiccation, therefore they prefer to live in wet environments. These environments include oceanic sea floors, freshwater systems, and damp soil.[3] | |||

The class Polychaeta are primarily benthic [[organisms]] that can live in saline, brackish, or freshwater environments. Their distribution in these areas are primarily controlled by the space available to them, the dissolved oxygen content in the water, the rate of movement of the water, and the relative salinity and temperature of the water to the Polychaeta.[4] Polychaetes play an important role in turnover of sediment on the ocean floor [8]. | |||

Oligochaetes are primarily found in the soil but a few are found in aquatic environments, and leeches are almost entirely aquatic or limited to humid areas.[3] | |||

== Morphology/Anatomy == | == Morphology/Anatomy == | ||

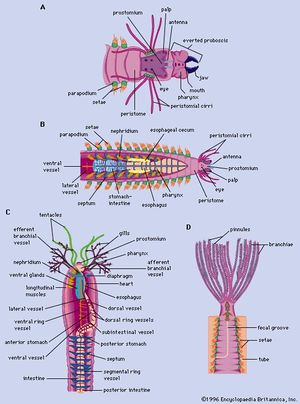

Annelids are bilaterally symmetrical animals. The entire body of an annelid is composed of segments. They are named after the Latin word "anellus" which means little ring.[2] These segments can grow in number as the annelid grows in length, with exception of leeches which can have 34 segments and grow by expanding those 34 segments.[3] Annelids also have setae, or chaetae, which are long filaments or hooked structures made up up many chitinous cylinders held together by sclerotinized proteins.[2] These seatae are important in anchoring the annelids down and to help them move up surfaces. | [[File:Polychaete.jpg|300px|thumb|right| Polychaete anatomy. a,b) free moving c,d) tube dwelling [8]]] | ||

Annelids are bilaterally symmetrical [[animals]]. The entire body of an annelid is composed of segments. They are named after the Latin word "anellus" which means little ring.[2] These segments can grow in number as the annelid grows in length, with exception of leeches which can have 34 segments and grow by expanding those 34 segments.[3] Annelids also have setae, or chaetae, which are long filaments or hooked structures made up up many chitinous cylinders held together by sclerotinized proteins.[2] These seatae are important in anchoring the annelids down and to help them move up surfaces. | |||

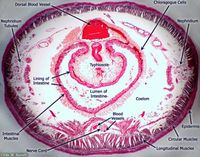

[[File:EarthwormCrossSection.jpg|200px|thumb|left| Cross section of an earthworm]] | |||

[[ | The digestive tract of an annelid is essentially one tube that runs from the mouth of the organism to the anus. The area between the inner cavity and the outside of the annelid is called the coelem. This area is filled with a coelemic fluid that also contains the other organ systems of the animals. This fluid is very important for a variety of functions of the organism such as locomotion, osmoregulation, and multiple metabolic processes among others. In polychaetes this fluid is also used to keep the worm's salt levels similar to the surrounding water. The coelmic fluids of leeches are filled with connective tissue and becomes more so as the leech ages. Oxygen is generally absorbed through the skin of the annelid and passed through the body by a closed circulatory system.[3] Leeches have well developed digestive glands called diverticula, all other annelids lack this[3]. | ||

The | The body of polychaetes is dependent on whether they are ocean-dwelling, sedentary, which live in tubes, or free-living. Most polychaetes breathe through their body wall, however some exhibit gill like structures. They also have sensory organs such as taste buds, eyes that may range in complexity[8]. | ||

- | Leeches are said to have evolved from ogligochaetes, they differ morphologically by having a set number of segments, rather than an ever growing number of segments. They have also lost the chaetae for movement but instead can use their anterior and posterior suckers for movement as well as feeding, which are also unique to them[9]. | ||

== Life Cycle and Reproduction == | |||

[[File:Bobbit Worm.jpg|200px|thumb|Right|''Eunice aphroditois'' | |||

or the Bobbit Worm, an aquatic predatory polychaete worm that buries beneath sediments to ambush prey]] | |||

====Polychaetes==== | |||

Many terrestrial annelids are hermaphroditic however, many polychaetes have defined male and female sexes for spawning[2]. Polychaete spawn near the surface marine environments. Males and females will release their gametes into the water where they are fertilized.[8] The larvae are usually free-living for sometime, using cilia for movement[8]. | |||

Other polychaetes are hermaphroditic while some reproduce by budding, where a part of the adult body breaks off and mature into a new individual[8]. | |||

Although most polychates can regenerate lost body parts, while not entirely known, their life span is thought to last anywhere from a month to three years depending on species. This can be dependent on reproductive cycles or the fact that they are slow and cannot escape predation[3]. | |||

== | ====Oligochaetes==== | ||

[[File:Earthwormsmating.jpg|200px|thumb|Left|Two earthworms | [[File:Earthwormsmating.jpg|200px|thumb|Left|Two earthworms exchanging sperm.]] | ||

Oligochaetes are also hermaphroditic, each individual posses both male and female reproductive organs. While they may appear to reproduce sexually, they are instead exchanging sperm which is then stored in sperm sacs[7]. The sperm is later released along with the eggs into a cocoon initially located on the clitellum. Other oligochaetes can reproduce parthenogenetically without fertilization by sperm[7]. Oligochaetes do not undergo a larval stage rather they simply exit the cocoon as small oligochaetes and grow larger as they become more mature[3]. Oligochaetes are able to regenerate lost body parts, but they do not do this forever, some [[earthworm]] species have been known to live up to ten years [3]. | |||

====Hirudinea==== | |||

Leeches are hermaphroditic but sexually meaning both sperm and eggs are need in order for fertilization to occur. Once fertlized eggs, any nuber from 1- 100 bunched together in a cocoon, can be deposited onto rocks or vegetation. Young leeches will hatch from the eggs. [3] | |||

Similarily to polychaetes not much is known about the life cycle or span of leeches. Some reproduce once and then die, and other may reproduce three times before they die[3]. | |||

== Role in Soil == | == Role in Soil == | ||

Oligochaetes are the | [[Oligochaetes]] are the primary annelids found in [[soil]], there are believed to be more than 5,000 earthworm species[7]. Earthworms are considered ecosystem engineers because of the role they play in the structure of soils and the diversity of the soil ecosystem. Earthworms either get their food from the surface leaf litter or the organic residue found in soil.[6] The majority of organics that an earthworm will ingest are from dead plant matter, but they will also consume living animals such as [[nematodes]] and other [[microfauna]].[6] Earthworms prefer foods with a high nitrogen content and they also eat to burrow as well. As they burrow they leave nutrient rich casts which are important for returning nutrients to the soil. This aerates the soil, provides more nutrients for living plants, and helps prevent erosion. These nutrient rich casts are a big reason why earthworms are important to [[agriculture]] and why they are sought out when planting an new field.[6] | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 47: | Line 57: | ||

3. Reish, D. J. (2013, December 18). Annelid. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.britannica.com/animal/annelid | 3. Reish, D. J. (2013, December 18). Annelid. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.britannica.com/animal/annelid | ||

4. Lardicci, C. , Abbiati, M. , Crema, R. , Morri, C. , Bianchi, C. N. and Castelli, A. (1993), The Distribution of Polychaetes Along Environmental Gradients: An Example from the Or betel I o Lagoon, Italy. Marine Ecology, 14: 35-52. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.1993.tb00363.x | 4. Lardicci, C. , Abbiati, M. , Crema, R. , Morri, C. , Bianchi, C. N. and Castelli, A. (1993), The Distribution of Polychaetes Along Environmental Gradients: An Example from the Or betel I o Lagoon, Italy. Marine [[Ecology]], 14: 35-52. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.1993.tb00363.x | ||

5. Annie Mercier, Sandrine Baillon, Jean-François Hamel,Life history and seasonal breeding of the deep-sea annelid Ophryotrocha sp. (Polychaeta: Dorvelleidae),Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers,Volume 91,2014,Pages 27-35,ISSN 0967-0637,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.007. | 5. Annie Mercier, Sandrine Baillon, Jean-François Hamel,Life history and seasonal breeding of the deep-sea annelid Ophryotrocha sp. (Polychaeta: Dorvelleidae),Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers,Volume 91,2014,Pages 27-35,ISSN 0967-0637,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.007. | ||

6. Lenardt, A. (2014, April 7). The Role of Earthworms in Soil Systems. Retrieved April 14, 2018, from https://blogs.unbc.ca/biol202/2014/04/07/the-role-of-earthworms-in-soil-systems/ | 6. Lenardt, A. (2014, April 7). The Role of Earthworms in Soil Systems. Retrieved April 14, 2018, from https://blogs.unbc.ca/biol202/2014/04/07/the-role-of-earthworms-in-soil-systems/ | ||

[7]“4.4 The [[Macrofauna]].” Fundamentals of [[Soil Ecology]], by David C. Coleman et al., Elsevier ; London, 2018, pp. 132–168. | |||

[8]annelid - Polychaetes.[[https://www.britannica.com/animal/polychaete]] | |||

[9]Iyer, R. G., D. V. Rogers, M. Levine, C. J. Winchell, and D. A. Weisblat. 2019. Reproductive differences among species, and between individuals and cohorts, in the leech genus Helobdella (Lophotrochozoa; Annelida; Clitellata; Hirudinida; Glossiphoniidae), with implications for reproductive resource allocation in hermaphrodites. PLOS ONE 14:e0214581.[[https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0214581]] | |||

''Image Sources'' | |||

1.Taken By Phynix Davis in Roosevelt Park on 4/14/2018 | |||

2.https://imgur.com/gallery/7oQDJ | |||

3. http://www.savalli.us/BIO385/Diversity/09.Annelida.html | |||

4.http://www.soilanimals.com/look/soil-food-web | |||

5. https://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/animals/stories/bobbitt-worm-blue-planet | |||

Latest revision as of 13:44, 1 May 2025

Annelids, or segmented worms, are segmented bilaterian invertebrates that are very important to a variety of marine and terrestrial environments. All annelids have a central body cavity called a coelom, bristles called setae, and segments called annulations which they are named after. There are three major groups of of annelids; the class Polychaeta which are almost entirely marine in nature and the subclasses of Oligochaeta which are earthworms and their relatives, and Hirudinea which are leeches. Among these groups there are approximately 17,000 described species. Many of the species of annelids reproduce sexually and are hermaphroditic, but some are able to asexually reproduce. Annelids are found across the entire planet in almost every kind of environment imaginable. Annelids are generally soft tissue organisms, but there is evidence of them in the fossil record dating back to the Ordovician period.

Classification

Annelids belong to the clade Lophotrochozoa. This clade also includes the phyla Mollusca, Sipuncula, Brachiopodia, and Phorondia. [1] The two major groups of annelids are the clitellates and polychaetes. Clitellates include members of the subclasses oligochaeta (eg. earthworms) and hirundinea (leeches). Oligochaetea are primarily terestrial, preferring damp soil, while leeches are mostly made up of freshwater aquatic species.

Polychaetes are almost entirely made up of marine species, but a few freshwater species do exist.[1] There are abut 17,000 species of annelid and about 12,000 of them are members of polychaetes. Polychaetes are then divided into two groups dependent on if they are mostly mobile throughout life or if they live in tubes or burrows for the majority of their existence. There are also about 42 different groups of clitellates[2].

Distribution and Habitat

Annelids, due to their incredible diversity, live in nearly every habitat on planet, however they have no means of protecting themselves from desiccation, therefore they prefer to live in wet environments. These environments include oceanic sea floors, freshwater systems, and damp soil.[3]

The class Polychaeta are primarily benthic organisms that can live in saline, brackish, or freshwater environments. Their distribution in these areas are primarily controlled by the space available to them, the dissolved oxygen content in the water, the rate of movement of the water, and the relative salinity and temperature of the water to the Polychaeta.[4] Polychaetes play an important role in turnover of sediment on the ocean floor [8].

Oligochaetes are primarily found in the soil but a few are found in aquatic environments, and leeches are almost entirely aquatic or limited to humid areas.[3]

Morphology/Anatomy

Annelids are bilaterally symmetrical animals. The entire body of an annelid is composed of segments. They are named after the Latin word "anellus" which means little ring.[2] These segments can grow in number as the annelid grows in length, with exception of leeches which can have 34 segments and grow by expanding those 34 segments.[3] Annelids also have setae, or chaetae, which are long filaments or hooked structures made up up many chitinous cylinders held together by sclerotinized proteins.[2] These seatae are important in anchoring the annelids down and to help them move up surfaces.

The digestive tract of an annelid is essentially one tube that runs from the mouth of the organism to the anus. The area between the inner cavity and the outside of the annelid is called the coelem. This area is filled with a coelemic fluid that also contains the other organ systems of the animals. This fluid is very important for a variety of functions of the organism such as locomotion, osmoregulation, and multiple metabolic processes among others. In polychaetes this fluid is also used to keep the worm's salt levels similar to the surrounding water. The coelmic fluids of leeches are filled with connective tissue and becomes more so as the leech ages. Oxygen is generally absorbed through the skin of the annelid and passed through the body by a closed circulatory system.[3] Leeches have well developed digestive glands called diverticula, all other annelids lack this[3].

The body of polychaetes is dependent on whether they are ocean-dwelling, sedentary, which live in tubes, or free-living. Most polychaetes breathe through their body wall, however some exhibit gill like structures. They also have sensory organs such as taste buds, eyes that may range in complexity[8].

Leeches are said to have evolved from ogligochaetes, they differ morphologically by having a set number of segments, rather than an ever growing number of segments. They have also lost the chaetae for movement but instead can use their anterior and posterior suckers for movement as well as feeding, which are also unique to them[9].

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Polychaetes

Many terrestrial annelids are hermaphroditic however, many polychaetes have defined male and female sexes for spawning[2]. Polychaete spawn near the surface marine environments. Males and females will release their gametes into the water where they are fertilized.[8] The larvae are usually free-living for sometime, using cilia for movement[8].

Other polychaetes are hermaphroditic while some reproduce by budding, where a part of the adult body breaks off and mature into a new individual[8].

Although most polychates can regenerate lost body parts, while not entirely known, their life span is thought to last anywhere from a month to three years depending on species. This can be dependent on reproductive cycles or the fact that they are slow and cannot escape predation[3].

Oligochaetes

Oligochaetes are also hermaphroditic, each individual posses both male and female reproductive organs. While they may appear to reproduce sexually, they are instead exchanging sperm which is then stored in sperm sacs[7]. The sperm is later released along with the eggs into a cocoon initially located on the clitellum. Other oligochaetes can reproduce parthenogenetically without fertilization by sperm[7]. Oligochaetes do not undergo a larval stage rather they simply exit the cocoon as small oligochaetes and grow larger as they become more mature[3]. Oligochaetes are able to regenerate lost body parts, but they do not do this forever, some earthworm species have been known to live up to ten years [3].

Hirudinea

Leeches are hermaphroditic but sexually meaning both sperm and eggs are need in order for fertilization to occur. Once fertlized eggs, any nuber from 1- 100 bunched together in a cocoon, can be deposited onto rocks or vegetation. Young leeches will hatch from the eggs. [3]

Similarily to polychaetes not much is known about the life cycle or span of leeches. Some reproduce once and then die, and other may reproduce three times before they die[3].

Role in Soil

Oligochaetes are the primary annelids found in soil, there are believed to be more than 5,000 earthworm species[7]. Earthworms are considered ecosystem engineers because of the role they play in the structure of soils and the diversity of the soil ecosystem. Earthworms either get their food from the surface leaf litter or the organic residue found in soil.[6] The majority of organics that an earthworm will ingest are from dead plant matter, but they will also consume living animals such as nematodes and other microfauna.[6] Earthworms prefer foods with a high nitrogen content and they also eat to burrow as well. As they burrow they leave nutrient rich casts which are important for returning nutrients to the soil. This aerates the soil, provides more nutrients for living plants, and helps prevent erosion. These nutrient rich casts are a big reason why earthworms are important to agriculture and why they are sought out when planting an new field.[6]

References

1. Parry, L. , Tanner, A. , Vinther, J. and Smith, A. (2014), The origin of annelids. Palaeontology, 57: 1091-1103. doi:10.1111/pala.12129

2. Rouse, G. W. (2001). Annelida (Segmented Worms). In eLS, (Ed.). doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001599

3. Reish, D. J. (2013, December 18). Annelid. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.britannica.com/animal/annelid

4. Lardicci, C. , Abbiati, M. , Crema, R. , Morri, C. , Bianchi, C. N. and Castelli, A. (1993), The Distribution of Polychaetes Along Environmental Gradients: An Example from the Or betel I o Lagoon, Italy. Marine Ecology, 14: 35-52. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.1993.tb00363.x

5. Annie Mercier, Sandrine Baillon, Jean-François Hamel,Life history and seasonal breeding of the deep-sea annelid Ophryotrocha sp. (Polychaeta: Dorvelleidae),Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers,Volume 91,2014,Pages 27-35,ISSN 0967-0637,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.007.

6. Lenardt, A. (2014, April 7). The Role of Earthworms in Soil Systems. Retrieved April 14, 2018, from https://blogs.unbc.ca/biol202/2014/04/07/the-role-of-earthworms-in-soil-systems/

[7]“4.4 The Macrofauna.” Fundamentals of Soil Ecology, by David C. Coleman et al., Elsevier ; London, 2018, pp. 132–168.

[8]annelid - Polychaetes.[[1]]

[9]Iyer, R. G., D. V. Rogers, M. Levine, C. J. Winchell, and D. A. Weisblat. 2019. Reproductive differences among species, and between individuals and cohorts, in the leech genus Helobdella (Lophotrochozoa; Annelida; Clitellata; Hirudinida; Glossiphoniidae), with implications for reproductive resource allocation in hermaphrodites. PLOS ONE 14:e0214581.[[2]]

Image Sources

1.Taken By Phynix Davis in Roosevelt Park on 4/14/2018

2.https://imgur.com/gallery/7oQDJ

3. http://www.savalli.us/BIO385/Diversity/09.Annelida.html

4.http://www.soilanimals.com/look/soil-food-web

5. https://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/animals/stories/bobbitt-worm-blue-planet