Red Salamander: Difference between revisions

Creating Red Salamander Page MK. I |

No edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; float:right; margin-left: 10px; | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; float:right; margin-left: 10px; | ||

|+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb(240,150,110)|'''Scientific Classification'''<ref name="NatureServe">Pseudotriton ruber | NatureServe Explorer. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.101775/Pseudotriton_ruber</ref> <ref name="ADW">Miller, R. (n.d.). Pseudotriton ruber (Red Salamander). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pseudotriton_ruber/</ref> <ref name="Red Salamander Photo 1">Todd Pierson. Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://herpsofnc.org/red-salamander/</ref> | |+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb(240,150,110)|'''Scientific Classification'''<ref name="NatureServe">Pseudotriton ruber | NatureServe Explorer. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.101775/Pseudotriton_ruber</ref> <ref name="ADW">Miller, R. (n.d.). Pseudotriton ruber (Red Salamander). Animal [[Diversity]] Web. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pseudotriton_ruber/</ref> <ref name="Red Salamander Photo 1">Todd Pierson. Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://herpsofnc.org/red-salamander/</ref> | ||

|colspan="2" |[[File:Red Salamander Cover Pic.jpg|451px|right|Caption]] | |colspan="2" |[[File:Red Salamander Cover Pic.jpg|451px|right|Caption]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Psuedotriton ruber, more commonly known as the Red Salamander, are larger amphibians belonging to the Plethodontidae family. In latin, ruber means "red" and in greek psuedotriton means "false god" in reference to Triton, the son of Posidon. Others say that this could also mean "false newt" <ref name="AmphibiaWeb">AmphibiaWeb—Pseudotriton ruber. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://amphibiaweb.org/species/4198</ref> <ref name="VHS">Virginia Herpetological Society. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from http://www.virginiaherpetologicalsociety.com</ref>. These are amphibians who have a redish orangish skin pigmentation with black spots along the back and chin, a yellow iris, and a rather shorter tail. <ref name="DWR">Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://dwr.virginia.gov/wildlife/information/northern-red-salamander/</ref>. The size of Red [[Salamanders]] can very between 11 to 18 cm, or 4.33 to 7.09 in, with females tending to be slightly larger and all contain 16 grooves along their body. As they age, it has been shown that adults tend to turn a purplish brown, loosing their vibrant colors over time <ref name="Wildlife Resources Agency">Red Salamander | State of Tennessee, Wildlife Resources Agency. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.tn.gov/twra/wildlife/amphibians/salamanders/red-salamander.html</ref>. There are 4 infraspecies within this species (Pseudotriton ruber nitidus, Pseudotriton ruber ruber, Pseudotriton ruber schencki, and Pseudotriton ruber vioscai), and they often get mistaken for Mud Salamanders. Their yellow iris is what separates them from the Mud Salamander species, who has a brown iris <ref name="NatureServe"></ref>. | |||

== | == Ecology == | ||

Red Salamanders are found in colder springs, seepages, and springs in forested riparian corridors, but can also live away from aquatic environments in more woody environments. <ref name="Indiana">Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber)—Indiana Herp Atlas. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.inherpatlas.org/species/pseudotriton_ruber</ref>. Some terrestrial habitats include under rocks, logs, or [[moss]] within woodland ravines or open fields <ref name="Wildlife Resources Agency"></ref>. The Red Salamander resides between altitudes of sea level and 1500 meters. The most common habitat for these amphibians is within deeper springs because of the more consistent temperature throughout the year, especially in colder months. When it gets warmer such as spring and summer, we can see the salamanders begin to emerge from these water bodies and take on the more terrestrial habitats previously discussed <ref name="ADW"></ref>. The scope of their habitat is quite wide, found mostly with the Eastern United States. They are found as far north as New York within the Hudson River all the way to the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana, and everything in between <ref name="Monaco">Mazza, G. (2011, January 28). Pseudotriton ruber. Monaco Nature Encyclopedia. https://www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com/pseudotriton-ruber/?lang=en</ref>. | |||

</br></br> | </br></br> | ||

[[File: | [[File:Red Salamander Eggs.jpg|501px|left|thumb|Red Salamander Laying Eggs <ref name="Monaco"></ref>]] | ||

== Reproduction and Life Cycle == | == Reproduction and Life Cycle == | ||

Mating season for the Red Salamander occurs annually, usually in the summer, but can vary depending on the geographic location <ref name="AmphibiaWeb"></ref><ref name="Indiana"></ref>. Courtship, which is the behaviors that [[animals]] use to attract a potential mate, can happen with multiple partners for both the male and female sexes <ref name = "ADW"></ref>. It is initiated by the male with help from his hedonic gland (located at the tip of the chin and releases a sexual stimulant) and the courtship contains some head rubbing between the salamanders and a tail-straddling walk. The male secretes a spermatophore for the female that can be later used for fertilization (max production of 2 per night), but the female must pick up the sperm packet so the male must continue to perform a dance and gesture towards the packet. If and after the female collects the packet, the two separate slowly after <ref name="AmphibiaWeb"></ref><ref name="ADW"></ref>. | |||

<br></br> | |||

After pickup, the female is able to store the spermatophore for quite a long time until she believes that the conditions are right for laying her eggs. Eggs are laid in the fall and early winter and the amount of eggs laid can range between 29-130 eggs, averaging 80 per batch <ref name="Monaco"></ref>. The batches are attached beneath rocks and logs, or within caves, with the help of water. The female then broods the eggs for 2-3 months until they are ready to hatch <ref name="ADW"></ref><ref name="AmphibiaWeb"></ref>. Once hatched, the larvae become independent, contain external gills and persist within the larval stage for 1.5 to 3.5 years. They metamorphosize between the spring and autumn seasons of their third year and then persist in their "juvenile terrestrial" stage for about one year for males and two years for females. This means males reach the adult stage around 4 years old and females around 5 years old <ref name="Monaco"></ref><ref name="ADW"></ref>. | |||

<br></br> | |||

An interesting behavior that has been observed within the males is their lack of aggression to one another. On the contrary, they try to sabotage the reproductive success of their male counterparts to improve their chances of reproducing. Males have been found to participate in courtship rituals with one another, trying to get the other male to produce a spermatophore. Being that Red Salamanders can only produce up to 2 sperm packets per day, this significantly cuts down the reproductive competition within the area. It has not been observed as a mistaking of the other's sex, neither is it deemed to be acts of homosexuality; it is simply a method of "sexual interference" to try an maximize ones own reproductive success <ref name="ADW"></ref><ref name="Monaco"></ref>. | |||

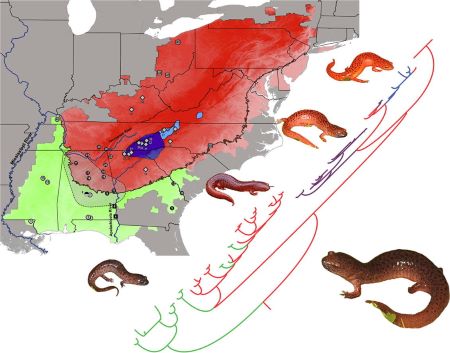

[[File:Red Salamander Habitat.jpg|451px|right|thumb|The habitat of each of the 4 Red Salamander species <ref name="Habitat">Folt, B., Garrison, N., Guyer, C., Rodriguez, J., & Bond, J. E. (2016). Phylogeography and evolution of the Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 98, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.016</ref>]] | |||

== Diet and Feeding Behaviors == | == Diet and Feeding Behaviors == | ||

The diet of the red salamander consists of many smaller [[invertebrates]], both terrestrial and aquatic <ref name="NorthCarolina">Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://herpsofnc.org/red-salamander/</ref>. They follow a generalist diet, and can consume [[organisms]] such as snails, spiders, [[insects]], and even other salamanders if the conditions are right <ref name="Monaco"></ref>. They feed during the night and utilize their tongue to capture prey quickly and efficiently. Similar to frogs, they protract their tongues with incredible speed until the tip of their tongue sticks to the prey. Once caught, the salamander retracts its tongue to quickly consume the organism. For larger prey, they may also lunge at the prey to disable them while the salamander feeds. Younger larvae have a slightly smaller pallette, consisting of primarily aquatic species like flies, salamander larvae, and crustaceans <ref name="ADW"></ref>. The predators of the Red Salamander include snakes, birds, skunks, shrews, and racoons <ref name="AmphibiaWeb"></ref>. | |||

== Defense Mechanisms == | |||

The three primary defense mechanisms the Red Salamander utilizes is color, behavior, and poison. As you can see the Red Salamander is bright red, participating in aposematic coloration. The Eastern Newt is an organism who is deemed highly toxic to predators, so being that the Red Salamander is of a similar color scheme, predators tend to stay away from the species <ref name="DWR"></ref><ref name="Wildlife Resources Agency"></ref>. If the color does not turn predators away, the next line of defense is the physical behaviors of the Red Salamander. It has been shown that the Red Salamander may mimic the behaviors of the Eastern Newt as well, curling up its body, elevating its rear legs and tail, tucking its head underneath its tail, and swaying its tail back and forth <ref name="ADW"></ref><ref name="Monaco"></ref>. The last mechanism that the Red Salamander uses to avoid predation is through its production of the toxic substance found on its outside layer. Pseudotritontoxin is the chemical found on Red Salamanders and is comparable to tetrodotoxin which is found in species like the Eastern Newt. When exposed to mice, pseudotritontoxin can cause "hyperextension of hind legs and lower back, extreme irritability, severe hypothermia, quiescence, prolonged debility, coma," and in extreme cases death. The concentration of this chemical is most common in the back of the Red Salamander <ref name="Toxicity">Brandon, R. A., & Huheey, J. E. (1981). Toxicity in the plethodontid salamanders Pseudotriton ruber and Pseudotriton montanus (Amphibia, Caudata). Toxicon, 19(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-0101(81)90114-8</ref>. The Red Salamander is non lethal and unless eaten, should not cause any significant adverse health impacts <ref name="Indiana"></ref>. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 21:59, 7 May 2025

| |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum: | Craniata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Superclass: | Gnathostomata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Subclass: | Lissamphibia |

| Order: | Caudata |

| Family: | Plethodontidae |

| Genus: | Pseudotriton |

Psuedotriton ruber, more commonly known as the Red Salamander, are larger amphibians belonging to the Plethodontidae family. In latin, ruber means "red" and in greek psuedotriton means "false god" in reference to Triton, the son of Posidon. Others say that this could also mean "false newt" [4] [5]. These are amphibians who have a redish orangish skin pigmentation with black spots along the back and chin, a yellow iris, and a rather shorter tail. [6]. The size of Red Salamanders can very between 11 to 18 cm, or 4.33 to 7.09 in, with females tending to be slightly larger and all contain 16 grooves along their body. As they age, it has been shown that adults tend to turn a purplish brown, loosing their vibrant colors over time [7]. There are 4 infraspecies within this species (Pseudotriton ruber nitidus, Pseudotriton ruber ruber, Pseudotriton ruber schencki, and Pseudotriton ruber vioscai), and they often get mistaken for Mud Salamanders. Their yellow iris is what separates them from the Mud Salamander species, who has a brown iris [1].

Ecology

Red Salamanders are found in colder springs, seepages, and springs in forested riparian corridors, but can also live away from aquatic environments in more woody environments. [8]. Some terrestrial habitats include under rocks, logs, or moss within woodland ravines or open fields [7]. The Red Salamander resides between altitudes of sea level and 1500 meters. The most common habitat for these amphibians is within deeper springs because of the more consistent temperature throughout the year, especially in colder months. When it gets warmer such as spring and summer, we can see the salamanders begin to emerge from these water bodies and take on the more terrestrial habitats previously discussed [2]. The scope of their habitat is quite wide, found mostly with the Eastern United States. They are found as far north as New York within the Hudson River all the way to the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana, and everything in between [9].

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Mating season for the Red Salamander occurs annually, usually in the summer, but can vary depending on the geographic location [4][8]. Courtship, which is the behaviors that animals use to attract a potential mate, can happen with multiple partners for both the male and female sexes [2]. It is initiated by the male with help from his hedonic gland (located at the tip of the chin and releases a sexual stimulant) and the courtship contains some head rubbing between the salamanders and a tail-straddling walk. The male secretes a spermatophore for the female that can be later used for fertilization (max production of 2 per night), but the female must pick up the sperm packet so the male must continue to perform a dance and gesture towards the packet. If and after the female collects the packet, the two separate slowly after [4][2].

After pickup, the female is able to store the spermatophore for quite a long time until she believes that the conditions are right for laying her eggs. Eggs are laid in the fall and early winter and the amount of eggs laid can range between 29-130 eggs, averaging 80 per batch [9]. The batches are attached beneath rocks and logs, or within caves, with the help of water. The female then broods the eggs for 2-3 months until they are ready to hatch [2][4]. Once hatched, the larvae become independent, contain external gills and persist within the larval stage for 1.5 to 3.5 years. They metamorphosize between the spring and autumn seasons of their third year and then persist in their "juvenile terrestrial" stage for about one year for males and two years for females. This means males reach the adult stage around 4 years old and females around 5 years old [9][2].

An interesting behavior that has been observed within the males is their lack of aggression to one another. On the contrary, they try to sabotage the reproductive success of their male counterparts to improve their chances of reproducing. Males have been found to participate in courtship rituals with one another, trying to get the other male to produce a spermatophore. Being that Red Salamanders can only produce up to 2 sperm packets per day, this significantly cuts down the reproductive competition within the area. It has not been observed as a mistaking of the other's sex, neither is it deemed to be acts of homosexuality; it is simply a method of "sexual interference" to try an maximize ones own reproductive success [2][9].

Diet and Feeding Behaviors

The diet of the red salamander consists of many smaller invertebrates, both terrestrial and aquatic [11]. They follow a generalist diet, and can consume organisms such as snails, spiders, insects, and even other salamanders if the conditions are right [9]. They feed during the night and utilize their tongue to capture prey quickly and efficiently. Similar to frogs, they protract their tongues with incredible speed until the tip of their tongue sticks to the prey. Once caught, the salamander retracts its tongue to quickly consume the organism. For larger prey, they may also lunge at the prey to disable them while the salamander feeds. Younger larvae have a slightly smaller pallette, consisting of primarily aquatic species like flies, salamander larvae, and crustaceans [2]. The predators of the Red Salamander include snakes, birds, skunks, shrews, and racoons [4].

Defense Mechanisms

The three primary defense mechanisms the Red Salamander utilizes is color, behavior, and poison. As you can see the Red Salamander is bright red, participating in aposematic coloration. The Eastern Newt is an organism who is deemed highly toxic to predators, so being that the Red Salamander is of a similar color scheme, predators tend to stay away from the species [6][7]. If the color does not turn predators away, the next line of defense is the physical behaviors of the Red Salamander. It has been shown that the Red Salamander may mimic the behaviors of the Eastern Newt as well, curling up its body, elevating its rear legs and tail, tucking its head underneath its tail, and swaying its tail back and forth [2][9]. The last mechanism that the Red Salamander uses to avoid predation is through its production of the toxic substance found on its outside layer. Pseudotritontoxin is the chemical found on Red Salamanders and is comparable to tetrodotoxin which is found in species like the Eastern Newt. When exposed to mice, pseudotritontoxin can cause "hyperextension of hind legs and lower back, extreme irritability, severe hypothermia, quiescence, prolonged debility, coma," and in extreme cases death. The concentration of this chemical is most common in the back of the Red Salamander [12]. The Red Salamander is non lethal and unless eaten, should not cause any significant adverse health impacts [8].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pseudotriton ruber | NatureServe Explorer. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.101775/Pseudotriton_ruber

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Miller, R. (n.d.). Pseudotriton ruber (Red Salamander). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pseudotriton_ruber/

- ↑ Todd Pierson. Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://herpsofnc.org/red-salamander/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 AmphibiaWeb—Pseudotriton ruber. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://amphibiaweb.org/species/4198

- ↑ Virginia Herpetological Society. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from http://www.virginiaherpetologicalsociety.com

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://dwr.virginia.gov/wildlife/information/northern-red-salamander/

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Red Salamander | State of Tennessee, Wildlife Resources Agency. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.tn.gov/twra/wildlife/amphibians/salamanders/red-salamander.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber)—Indiana Herp Atlas. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.inherpatlas.org/species/pseudotriton_ruber

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Mazza, G. (2011, January 28). Pseudotriton ruber. Monaco Nature Encyclopedia. https://www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com/pseudotriton-ruber/?lang=en

- ↑ Folt, B., Garrison, N., Guyer, C., Rodriguez, J., & Bond, J. E. (2016). Phylogeography and evolution of the Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 98, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.016

- ↑ Red Salamander. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://herpsofnc.org/red-salamander/

- ↑ Brandon, R. A., & Huheey, J. E. (1981). Toxicity in the plethodontid salamanders Pseudotriton ruber and Pseudotriton montanus (Amphibia, Caudata). Toxicon, 19(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-0101(81)90114-8