Naked Mole-Rat: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Naked mole-rats''' are fossorial [[ | '''Naked mole-rats''' are small, fossorial rodents found mainly in Kenya and the Horn of Africa. They live in long, complex burrows and rarely venture aboveground. Their ability to thrive in the harsh conditions of subterranean Africa classifies them as [[extremophiles]], and they have developed a number of unique traits seldom seen elsewhere in the animal kingdom. These include reduced pain sensitivity, cancer immunity, and eusociality. | ||

<ref name="microbio">Holtze, Susanne, Stanton Braude, Alemayehu Lemma, Rosie Koch, Michaela Morhart, Karol Szafranski, Matthias Platzer, Fitsum Alemayehu, Frank Goeritz, and Thomas Bernd Hildebrandt. “The Microenvironment of Naked Mole‐rat Burrows in East Africa.” African journal of [[ecology]] 56, no. 2 (2018): 279–289.</ref> | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; float:right; margin-left: 10px; | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; float:right; margin-left: 10px; | ||

|+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb( | |+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb(0,204,102)|'''Naked mole-rat''' | ||

|+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb( | <ref> Mehgan, Murphy. ''The disease-resistant naked mole-rat''. Smithsonian Institution. https://critter.science/the-disease-resistant-naked-mole-rat/</ref> | ||

|+ !colspan="2" style="min-width:12em; text-align: center; background-color: rgb(0,204,102)|'''Taxonomy <ref>“Heterocephalus glaber.” itis.gov, n.d. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=584677#null. </ref>''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

| colspan="2" |[[File: | | colspan="2" |[[File:molerat2.jpg|300px|Naked mole-rat]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Kingdom | ! Kingdom | ||

| Line 12: | Line 14: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Phylum | ! Phylum | ||

| | | Chordata | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Class | ! Class | ||

| | | Mammalia | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Order | ! Order | ||

| | | Rodentia | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Family | ! Family | ||

| | | Bathyergidae | ||

|- | |||

! Genus | |||

| Heterocephalus | |||

|- | |||

! Species | |||

| Heterocephalus glaber | |||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Anatomy== | ==Anatomy== | ||

Naked mole rats have very poor eyesight and hearing. Instead, these creatures rely mostly on their sense of touch to navigate their burrows and are especially sensitive to vibrations. True to their name, they lack fur on their bodies, which exposes their cylindrical bodies and loose, pale, wrinkled skin. Their body shape and loose skin facilitate squeezing through the tight corridors of their burrows. However, they do have around 40 thin, whisker-like hairs on each side of their bodies that are sensitive to physical stimulation. The skin itself has also been shown to be immune to certain sources of pain. Their burrows usually have a very high carbon dioxide concentration, which in most creatures would cause pain due to tissue acidosis. The mole rat, however, is immune to this. <ref name = "blind"/> | |||

<br/> | |||

Besides their "naked" bodies, the other most striking part of the creature's anatomy is its large incisors. The jaw makes up about 25% of the creature's musculature, and it uses this muscle for a variety of tasks. The incisors are the primary tool used for digging their complex subterranean network of burrows. Additionally, they use their teeth as a transportation mechanism for food, debris, and their young. | |||

<ref name = "blind">Browe, Brigitte M., Emily N. Vice, and Thomas J. Park. “Naked Mole‐Rats: Blind, Naked, and Feeling No Pain.” Anatomical Record 303 (2020): 77–88. </ref> | |||

==Habitat and Distribution== | ==Habitat and Distribution== | ||

[[File: | [[File:molerathabitat.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Mole Rat Habitat <ref name="habitat">“Naked Mole Rat Range Map (Africa)” theanimalfiles.com, 2006. https://www.theanimalfiles.com/mammals/rodents/mole_rat_naked.html. </ref>]] | ||

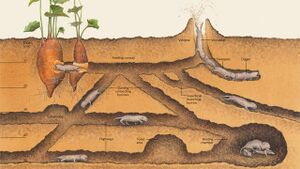

Naked mole rats spend almost their entire lives within complex networks of burrows underneath the grasslands of Eastern Africa. Specifically, they can be found around Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia. Aboveground, it is hot and arid, and there is very little rainfall. Despite this, their [[soil]] burrows have a relatively constant ambient temperature throughout the year. This is beneficial, as the mole rat is one of the few mammals that are poikilothermic and have considerably varying internal temperatures. If some outside condition alters the temperature within the burrow, the mole rats are able to sense this and reorganize and/or expand their burrows to compensate. These burrows exist in varying degrees of complexity, but often contain multiple nests, waste chambers, food storage chambers, and escape routes. | |||

<ref name = "blind"/> | |||

The largest of these burrows can even reach over 3,000 meters in length. | |||

<ref name="truth">Buffenstein, Rochelle, Vincent Amoroso, Blazej Andziak, Stanislav Avdieiev, Jorge Azpurua, Alison J. Barker, Nigel C. Bennett, et al. “The Naked Truth: a Comprehensive Clarification and Classification of Current ‘myths’ in Naked Mole‐rat Biology.” Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 97, no. 1 (2022): 115–140</ref> | |||

These sprawling tunnels help with [[soil]] aeration where air from surface-level tunnels (with a higher oxygen concentration) is able to mix with the air in deeper parts of the soil, thus creating a "plunger effect". <ref name= "microbio"/> | |||

<br/> | |||

The | Each burrow develops a distinct [[microclimate]] based on a host of conditions. The depth, slope, and soil compaction all contribute to this. The behavior of the colony itself also plays a role, as the population size and metabolic rate of the mole rats also affect the microclimate. The soil color determines how much heat from the sun is absorbed, and this is the main driver of temperature within a burrow. While mole rats are protected from the worst of the desert threats (climate extremes, predators, UV radiation), there are different problems that come with living perpetually underground. Food can be scarce, digging and maintaining these tunnels has a high energy cost, and gas exchange is impaired. Managing to survive despite these drawbacks classifies these creatures as [[extremophiles.]]<ref name = "microbio"/> | ||

[[File:moleratburrow.jpg|300px|thumb|left|Mole Rat Burrow<ref name="burrow">Digging the Underground Life. Photograph. The-Scientist.com. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.the-scientist.com/infographics/digging-the-underground-life-40923. </ref>]] | |||

[[File: | |||

== | ==Behavior and Reproduction== | ||

The naked mole rat is one of the few mammals that can be defined as "eusocial". To be considered eusocial, an organism must display a reproductive division of labor, generational overlap, and cooperative raising of the young. | |||

<ref name = "truth"/> | |||

Age and size are the main traits that determine an individual's position in the social hierarchy, with the oldest and largest occupying the topmost positions. There are multiple distinct roles that individuals perform in the colony, and the same individuals tend to keep the same role for long periods of time. Particularly, younger members tend to raise young, and older members tend to defend the colony. There is also a specialized role for [[foraging]], which involves tunneling until an individual finds an underground tuber. Food is then taken from inside the tuber, leaving the skin intact to facilitate the plant's regrowth. <ref name="microbio"/> | |||

<ref name = "blind"/> | |||

== | <br/> | ||

Similarly to certain [[insects]], the largest female is designated the "queen" and is the sole breeder. She uses pheromones and intimidation to suppress other reproductive activity in the colony except for a handful of chosen partners. These pheromones are released mainly through urination. | |||

<ref name = "reprod">Zhou, Shuzhi, Melissa M. Holmes, Nancy G. Forger, Bruce D. Goldman, Matthew B. Lovern, Alain Caraty, Imre Kalló, Christopher G. Faulkes, and Clive W. Coen. “Socially Regulated Reproductive Development: Analysis of GnRH-1 and Kisspeptin Neuronal Systems in Cooperatively Breeding Naked Mole-Rats (Heterocephalus Glaber).” Journal of comparative neurology (1911) 521, no. 13 (2013): 3003–3029.</ref> | |||

Dual-queen colonies can sometimes form, but this is exceptionally rare due to the reproductive suppression instituted by the original queen. <ref name="blind"/> | |||

==Longevity and Cancer Resistance== | |||

The naked mole rat is the longest-living rodent, often living to over 30 years old. It is also extremely resistant to abnormal tumor growth. Sequencing of the mole rat's genome suggests that these traits are due to this species' unique makeup of protein p53, which is a regulatory protein that often gets mutated in the presence of cancer. | |||

<ref name="genome">Keane, Michael, Thomas Craig, Jessica Alfoeldi, Aaron M. Berlin, Jeremy Johnson, Andrei Seluanov, Vera Gorbunova, et al. “The Naked Mole Rat Genome Resource: Facilitating Analyses of Cancer and Longevity-Related Adaptations.” BIOINFORMATICS 30, no. 24 (2014): 3558–3560.</ref> | |||

Additionally, many negative age-related effects rarely manifest in these creatures, such as neurodegeneration, loss of thermoregulatory capability, and loss of reproductive capability. A prevailing theory is that longer living species possess mitochondria that are better capable of consuming reactive oxygen species, or highly reactive molecules containing the element oxygen (H202, peroxide, for example). | |||

<ref name= 'mitochon">Munro, Daniel, Cécile Baldy, Matthew E. Pamenter, and Jason R. Treberg. “The Exceptional Longevity of the Naked Mole‐rat May Be Explained by Mitochondrial Antioxidant Defenses.” Aging cell 18, no. 3 (2019): e12916–n/a.</ref> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 23:51, 11 May 2023

Naked mole-rats are small, fossorial rodents found mainly in Kenya and the Horn of Africa. They live in long, complex burrows and rarely venture aboveground. Their ability to thrive in the harsh conditions of subterranean Africa classifies them as extremophiles, and they have developed a number of unique traits seldom seen elsewhere in the animal kingdom. These include reduced pain sensitivity, cancer immunity, and eusociality. [1]

| |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Rodentia |

| Family | Bathyergidae |

| Genus | Heterocephalus |

| Species | Heterocephalus glaber |

Anatomy

Naked mole rats have very poor eyesight and hearing. Instead, these creatures rely mostly on their sense of touch to navigate their burrows and are especially sensitive to vibrations. True to their name, they lack fur on their bodies, which exposes their cylindrical bodies and loose, pale, wrinkled skin. Their body shape and loose skin facilitate squeezing through the tight corridors of their burrows. However, they do have around 40 thin, whisker-like hairs on each side of their bodies that are sensitive to physical stimulation. The skin itself has also been shown to be immune to certain sources of pain. Their burrows usually have a very high carbon dioxide concentration, which in most creatures would cause pain due to tissue acidosis. The mole rat, however, is immune to this. [4]

Besides their "naked" bodies, the other most striking part of the creature's anatomy is its large incisors. The jaw makes up about 25% of the creature's musculature, and it uses this muscle for a variety of tasks. The incisors are the primary tool used for digging their complex subterranean network of burrows. Additionally, they use their teeth as a transportation mechanism for food, debris, and their young.

[4]

Habitat and Distribution

Naked mole rats spend almost their entire lives within complex networks of burrows underneath the grasslands of Eastern Africa. Specifically, they can be found around Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia. Aboveground, it is hot and arid, and there is very little rainfall. Despite this, their soil burrows have a relatively constant ambient temperature throughout the year. This is beneficial, as the mole rat is one of the few mammals that are poikilothermic and have considerably varying internal temperatures. If some outside condition alters the temperature within the burrow, the mole rats are able to sense this and reorganize and/or expand their burrows to compensate. These burrows exist in varying degrees of complexity, but often contain multiple nests, waste chambers, food storage chambers, and escape routes. [4] The largest of these burrows can even reach over 3,000 meters in length. [6] These sprawling tunnels help with soil aeration where air from surface-level tunnels (with a higher oxygen concentration) is able to mix with the air in deeper parts of the soil, thus creating a "plunger effect". [1]

Each burrow develops a distinct microclimate based on a host of conditions. The depth, slope, and soil compaction all contribute to this. The behavior of the colony itself also plays a role, as the population size and metabolic rate of the mole rats also affect the microclimate. The soil color determines how much heat from the sun is absorbed, and this is the main driver of temperature within a burrow. While mole rats are protected from the worst of the desert threats (climate extremes, predators, UV radiation), there are different problems that come with living perpetually underground. Food can be scarce, digging and maintaining these tunnels has a high energy cost, and gas exchange is impaired. Managing to survive despite these drawbacks classifies these creatures as extremophiles.[1]

Behavior and Reproduction

The naked mole rat is one of the few mammals that can be defined as "eusocial". To be considered eusocial, an organism must display a reproductive division of labor, generational overlap, and cooperative raising of the young. [6] Age and size are the main traits that determine an individual's position in the social hierarchy, with the oldest and largest occupying the topmost positions. There are multiple distinct roles that individuals perform in the colony, and the same individuals tend to keep the same role for long periods of time. Particularly, younger members tend to raise young, and older members tend to defend the colony. There is also a specialized role for foraging, which involves tunneling until an individual finds an underground tuber. Food is then taken from inside the tuber, leaving the skin intact to facilitate the plant's regrowth. [1] [4]

Similarly to certain insects, the largest female is designated the "queen" and is the sole breeder. She uses pheromones and intimidation to suppress other reproductive activity in the colony except for a handful of chosen partners. These pheromones are released mainly through urination.

[8]

Dual-queen colonies can sometimes form, but this is exceptionally rare due to the reproductive suppression instituted by the original queen. [4]

Longevity and Cancer Resistance

The naked mole rat is the longest-living rodent, often living to over 30 years old. It is also extremely resistant to abnormal tumor growth. Sequencing of the mole rat's genome suggests that these traits are due to this species' unique makeup of protein p53, which is a regulatory protein that often gets mutated in the presence of cancer. [9] Additionally, many negative age-related effects rarely manifest in these creatures, such as neurodegeneration, loss of thermoregulatory capability, and loss of reproductive capability. A prevailing theory is that longer living species possess mitochondria that are better capable of consuming reactive oxygen species, or highly reactive molecules containing the element oxygen (H202, peroxide, for example). [10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Holtze, Susanne, Stanton Braude, Alemayehu Lemma, Rosie Koch, Michaela Morhart, Karol Szafranski, Matthias Platzer, Fitsum Alemayehu, Frank Goeritz, and Thomas Bernd Hildebrandt. “The Microenvironment of Naked Mole‐rat Burrows in East Africa.” African journal of ecology 56, no. 2 (2018): 279–289.

- ↑ Mehgan, Murphy. The disease-resistant naked mole-rat. Smithsonian Institution. https://critter.science/the-disease-resistant-naked-mole-rat/

- ↑ “Heterocephalus glaber.” itis.gov, n.d. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=584677#null.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Browe, Brigitte M., Emily N. Vice, and Thomas J. Park. “Naked Mole‐Rats: Blind, Naked, and Feeling No Pain.” Anatomical Record 303 (2020): 77–88.

- ↑ “Naked Mole Rat Range Map (Africa)” theanimalfiles.com, 2006. https://www.theanimalfiles.com/mammals/rodents/mole_rat_naked.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Buffenstein, Rochelle, Vincent Amoroso, Blazej Andziak, Stanislav Avdieiev, Jorge Azpurua, Alison J. Barker, Nigel C. Bennett, et al. “The Naked Truth: a Comprehensive Clarification and Classification of Current ‘myths’ in Naked Mole‐rat Biology.” Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 97, no. 1 (2022): 115–140

- ↑ Digging the Underground Life. Photograph. The-Scientist.com. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.the-scientist.com/infographics/digging-the-underground-life-40923.

- ↑ Zhou, Shuzhi, Melissa M. Holmes, Nancy G. Forger, Bruce D. Goldman, Matthew B. Lovern, Alain Caraty, Imre Kalló, Christopher G. Faulkes, and Clive W. Coen. “Socially Regulated Reproductive Development: Analysis of GnRH-1 and Kisspeptin Neuronal Systems in Cooperatively Breeding Naked Mole-Rats (Heterocephalus Glaber).” Journal of comparative neurology (1911) 521, no. 13 (2013): 3003–3029.

- ↑ Keane, Michael, Thomas Craig, Jessica Alfoeldi, Aaron M. Berlin, Jeremy Johnson, Andrei Seluanov, Vera Gorbunova, et al. “The Naked Mole Rat Genome Resource: Facilitating Analyses of Cancer and Longevity-Related Adaptations.” BIOINFORMATICS 30, no. 24 (2014): 3558–3560.

- ↑ Munro, Daniel, Cécile Baldy, Matthew E. Pamenter, and Jason R. Treberg. “The Exceptional Longevity of the Naked Mole‐rat May Be Explained by Mitochondrial Antioxidant Defenses.” Aging cell 18, no. 3 (2019): e12916–n/a.